Andy Warhol silkscreen of Prince faces Supreme Court scrutiny in copyright dispute

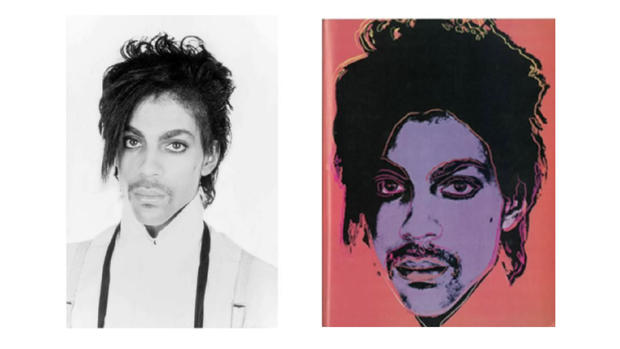

Washington — The Supreme Court on Wednesday wrestled with a copyright fight between rock-and-roll photographer Lynn Goldsmith and the Andy Warhol Foundation over the late artist's use of her 1981 photo of Prince as the basis for a silkscreen image.

The case could have ramifications for the entertainment industry and creators drawing inspiration from pre-existing works, and across more than 90 minutes of oral arguments, the justices invoked a number of cultural references, from "Lord of the Rings" to Norman Lear television shows to the Mona Lisa.

The court is weighing the foundation's claims that Warhol did not violate federal copyright law when he based a set of 16 silkscreens and sketches on Goldsmith's photo of Prince (who Justice Clarence Thomas revealed he was a fan of in the 1980s).

In the past the Supreme Court has allowed fair use if the work is "transformative," that is, if it "adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message." The law also considers whether the use of a work is for commercial or noncommercial use.

Some of the justices at times questioned whether Warhol's illustration of Prince constituted fair use under the Copyright Act, since his and Goldsmith's photograph had a similar commercial purpose.

"Isn't the classic thing with a photograph that it'll be used in stories about the subject of the photograph and, therefore, competing in the same market that this adaptation was used in?" Justice Brett Kavanaugh asked Roman Martinez, who argued on behalf of the Andy Warhol Foundation. "Namely, it was used in a story about Prince, not a story about Warhol."

Justice Sonia Sotomayor echoed Kavanaugh's sentiment, remarking that use of Warhol's illustration was "highly commercial."

"Goldsmith also licensed her photographs to magazines, just as Warhol's estate did," she said. "How is it that your [2016] license and Goldsmith's photographs do not share the same commercial purpose?"

The dispute stems back to the black-and-white photograph Goldsmith, considered a leading rock photographer, took of Prince in 1981, when he was an up-and-coming musician.

Three years later, as Prince shot to stardom, Vanity Fair commissioned Andy Warhol to create an illustration depicting Prince that would accompany a magazine article to be titled "Purple Fame." The magazine chose Goldsmith's 1981 portrait of Prince to use as "artist reference" for Warhol's silkscreen, paid Goldsmith a $400 licensing fee and agreed to credit her for the source photograph.

Warhol ended up creating 16 silkscreens and sketches known as the "Prince Series," and Vanity Fair ran one of the images, Purple Prince, in its November 1984 issue.

After Warhol's death in 1987, his foundation took ownership of the Prince Series, and, according to court filings, sold 12 of the 16 originals. The Andy Warhol Museum has the other four.

Prince died in 2016 and Conde Nast, Vanity Fair's parent company, licensed from the foundation an image known as Orange Prince, from the Prince Series, for the cover of a tribute magazine. The company paid a fee of roughly $10,250 to run the illustration on the cover.

Goldsmith did not receive payment or credit, and she warned the Andy Warhol Foundation of potential copyright infringement.

The two sides went to court, and a federal district court sided with the foundation, finding in part that Warhol's Prince Series works are protected by fair use, as the images are "transformative" and the illustrations "wash[ed] away the vulnerability and humanity Prince expresses in Goldsmith's photographs." The court also said the licensing market for Warhol and Goldsmith's works are different.

But the 2nd Circuit disagreed, finding Warhol's Prince Series was not transformative, and thus not considered fair use, and retained the "essential elements of the Goldsmith Photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements." Judges, the court said, "shouldn't assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue."

The Andy Warhol Foundation appealed to the Supreme Court, which is tasked with deciding whether a follow-on work is transformative because it conveys a different "meaning or message" from the original and therefore is fair use under the Copyright Act.

During arguments, Justice Samuel Alito questioned how a court is supposed to "determine the purpose of meaning, the message or meaning of works of art like a photograph or painting."

"You make it sound simple," he told Martinez. "But maybe it's not so simple, at least in some cases, to determine what is the meaning or the message of a work of art. There can be a lot of dispute what the meaning or message is."

Warhol's notoriety and the understanding of the messages conveyed in his work did not go unnoticed by the court.

Justice Elena Kagan suggested the approach advocated by the Andy Warhol Foundation benefits "from a certain kind of hindsight."

"We know who Andy Warhol was and what he was doing and what his works have been taken to mean. So it's easy to say that there's something importantly new in what he did with this image," she said. "But, if you imagine Andy Warhol as a struggling young artist, who we didn't know anything about, and then you look at these two images, you might be tempted to say something like, 'well, I don't get it. All he did was take somebody else's photograph and put some color into it.'"

Kagan continued: "We can't always count on the fact that Andy Warhol is Andy Warhol to know how to make this inquiry."

Lisa Blatt, who argued on behalf of Goldsmith, said the definition of transformative advocated by Warhol's foundation is "too easy to manipulate."

"Copyrights will be at the mercy of copycats," she warned the justices if the foundation prevails. "Anyone could turn Darth Vader into a hero or spin-off 'All in the Family' into 'The Jeffersons' without paying the creators a dime."

Supporting Warhol's foundation are documentary filmmakers, artists and curators who argue fair use is an integral protection at risk of being restricted if the Supreme Court upholds the 2nd Circuit's decision.

Siding with Goldsmith, meanwhile, are a range of entertainment industry groups, including the Recording Industry Association of America and Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, who argue that focusing on a secondary work's meaning or message would turn judges into art critics. The Justice Department is also backing Goldsmith in the dispute.

Blatt warned the court a decision siding with the Andy Warhol Foundation would have sweeping ramifications for creators, as any spinoff of a television show or book-to-movie adaptations would no longer require licenses.

The foundation argues Warhol is "a creative genius who imbued other people's art with his own distinctive style," she said. "But Spielberg did the same for films and Jimi Hendrix for music. Those giants still needed licenses."

A decision from the Supreme Court is expected by the end of June.