Supreme Court hears arguments on birth control coverage

In a case that pits religious freedom against a woman's access to contraceptives, the Supreme Court on Wednesday heard arguments on whether the Trump administration can make it easier for employers with religious and moral objections to opt out of providing free birth control coverage in their insurance plans.

The one-hour hearing — among of a handful to be heard via teleconference due to the coronavirus pandemic — consolidates two cases: Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania and Trump v. Pennsylvania. Wednesday's arguments are the latest battle in a multi-year war over whether employers with religious objections can opt out of the Affordable Care Act's requirement to provide contraceptives.

Previously, the Supreme Court has considered whether some organizations with religious objections to birth control can opt out of that rule. Wednesday's case is the reverse: the court will determine whether the Trump administration's attempt to allow broad exemptions to that rule is lawful.

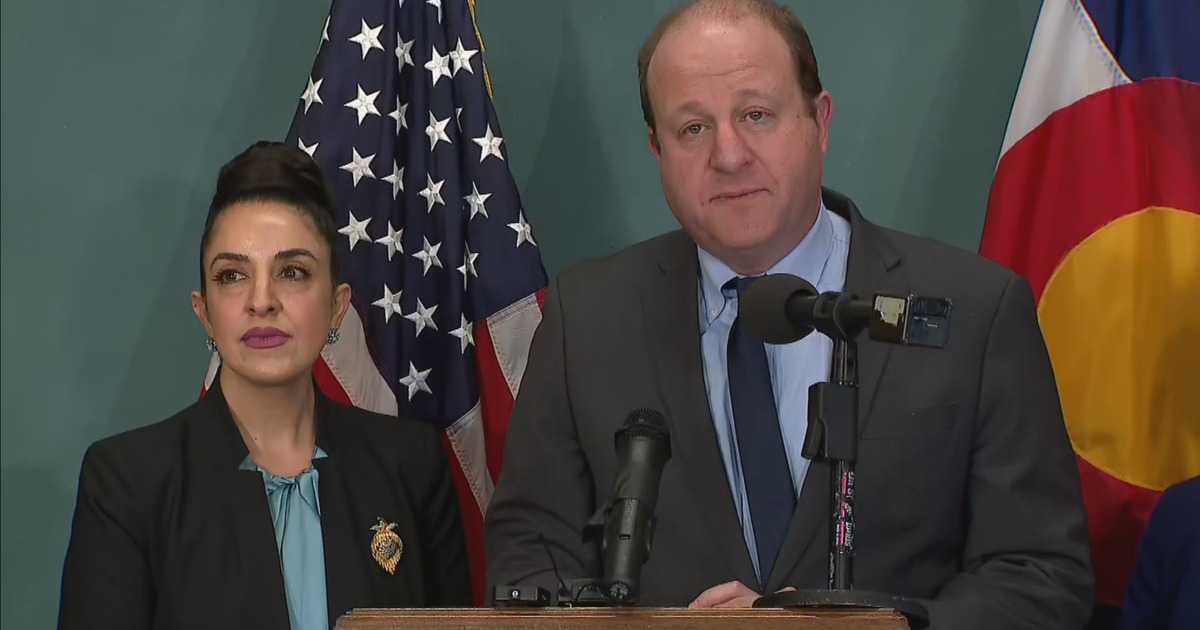

"Nobody should lose coverage because their boss believes contraception isn't morally acceptable," said Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro, whose office will be challenging the new regulation on Wednesday. "Contraception is medicine. Pure and simple." Shapiro spoke on a press call with reporters on Friday.

Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, employers must provide coverage for a full spectrum of birth control options at no cost to patients in their insurance plans. The impact has been tangible. Prior to the Affordable Care Act, one in three patients said they struggled to afford birth control, according to Shapiro. Today that number is 4%.

In 2017, the Trump administration issued new regulations that offer broad exemptions for employers that object to birth control, either for religious reasons or a "sincerely held moral" conviction. Pennsylvania and New Jersey challenged those exemptions and in May, a federal appeals court blocked the regulation from implementation.

In their decision, the three-judge panel, citing government data, wrote that up to 126,000 patients would lose access to insurance-covered birth control if the regulations were allowed to go into effect. Reproductive rights advocates say the number could be much higher.

The contraceptive requirement has already reached the Supreme Court twice. In 2014, the court ruled in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act protected family-owned companies who objected to the rule on religious grounds. These companies were offered an accommodation: If they objected, insurance companies or the government would pay for contraceptive coverage.

Many religiously-affiliated groups, like the Little Sisters of the Poor, a Roman Catholic group that offers help to senior citizens living in poverty, objected to that solution. The organization contended they were still involved in behavior that violated their faith.

In a 2016 opinion article published in The New York Times, Constance Veit, a nun at Little Sisters of the Poor, likened the process to schools rejecting soda machines on campuses, even if they're paid for by beverage companies: "The school simply doesn't want to be responsible for providing something it believes is bad for its students. It is the same with us."

That issue went to the Supreme Court in 2016 in Zubik v. Burwell. But the split court couldn't reach a solution, and instead pushed the case back to the lower courts where the question was never resolved.