Supreme Court leaves partisan gerrymandering to be decided by states

The Supreme Court is leaving the issue of drawing congressional districts to the states, ruling in a 5 to 4 decision that federal courts do not have a role to play in partisan gerrymandering. The ruling marked a major blow to efforts to limit the drawing of electoral districts for partisan gain.

"We conclude that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts," Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the majority opinion. He noted that the court had never struck down a partisan gerrymander as unconstitutional and has "struggled without success over the past several decades to discern judicially manageable standards for deciding such claims."

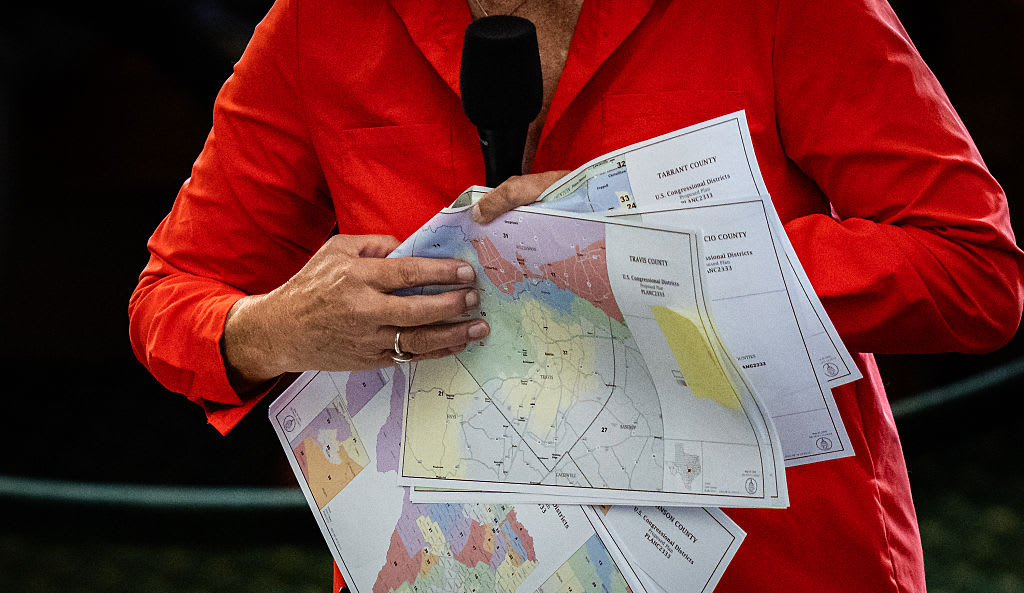

The Supreme Court considered a North Carolina case in which districts were drawn by the state's Republican-controlled legislature. Democrats said the move was rooted in partisan gerrymandering, the process by which the state's congressional maps are drawn to benefit one party over the other. In 2016, Republicans drew congressional districts that packed Democratic voters into the three districts that translated into landslide victories. In the 2018 midterm elections, the map produced smaller winning margins for Republican candidates, but in more districts.

The case also had implications for the state of Maryland, which saw its own challenges with partisan map drawing, in this case by Democrats. Republicans in 2011 disputed a single congressional district in western Maryland, held by a Republican incumbent for 20 years, drawn to benefit the state's Democratic party.

The hope for those challenging gerrymandering was that congressional district maps had been drawn in such a partisan manner that they violated the Constitution.

But determining what is politically fair -- or excessive -- in drawing congressional districts "poses basic questions that are political, not legal," Roberts wrote. "There are no legal standards discernible in the Constitution for making such judgments, let alone limited and precise standards that are clear, manageable, and politically neutral."

Roberts said that the court's ruling doesn't condone excessive partisan gerrymandering, and its conclusion wasn't to be interpeted as "condemn[ing] complaints about districting to echo into a void." The state courts, he pointed out, have already been addressing cases claiming dubious redistricting plans.

The Supreme Court vacated both the Maryland and North Carolina decisions and remanded the cases back to the states. The decision effectively reverses the outcome of rulings in Maryland, Michigan, North Carolina and Ohio, where courts had ordered new maps drawn, and ends proceedings in Wisconsin, where a retrial was supposed to take place this summer after the Supreme Court last year threw out a decision on procedural grounds.

The liberal justices on the court dissented. Justice Elena Kagan admonished the majority, writing in her dissent, "For the first time ever, this Court refuses to remedy a constitutional violation because it thinks the task beyond judicial capabilities."

She added, "Of all times to abandon the Court's duty to declare the law, this was not the one. The practices challenged in these cases imperil our system of government. Part of the Court's role in that system is to defend its foundations. None is more important than free and fair elections. With respect but deep sadness, I dissent."