Supreme Court "unable to identify" person who leaked abortion decision overturning Roe

Washington — The Supreme Court said Thursday that investigators have been "unable to identify a person responsible" for the unprecedented leak last May of a draft opinion in the blockbuster abortion case that overturned Roe v. Wade, but the probe is continuing.

A two-page statement of the court said a team led by Marshal of the Supreme Court Gail Curley performed forensic analysis and conducted follow-up interviews of certain court employees, but "has to date been unable to identify a person responsible by a preponderance of the evidence."

The eight-month investigation was prompted by the May 2 publication by Politico of a draft majority opinion from Justice Samuel Alito, which was circulated in February and indicated the high court would overturn Roe v. Wade.

In June, the court issued its formal opinion in the case — written by Alito and largely mirroring his draft — that ended the constitutional right to an abortion.

Chief Justice John Roberts assigned Curley and her staff to investigate the leak and denounced the unauthorized disclosure at the time, calling it a "betrayal of the confidences of the court." The Supreme Court revealed Thursday that it also consulted Michael Chertoff, former secretary of Homeland Security, to assess the marshal's probe.

The statement from the court concerning the leak investigation called the disclosure of the draft opinion "one of the worst breaches of trust in its history," and stressed the "integrity of judicial proceedings depends on the inviolability of internal deliberations."

"The leak was no mere misguided attempt at protest," the court said. "It was a grave assault on the judicial process."

In a 20-page report from the marshal accompanying the Supreme Court's statement, Curley said it is "unlikely" the leak stemmed from a hack of the court's IT systems by a person outside the court. But after examining the Supreme Court's computer devices, networks, printers and available call and text logs, investigators found "no forensic evidence indicating who disclosed the draft opinion."

Curley's investigative team included attorneys and federal investigators with experience in criminal, administrative and cyber investigations, and they conducted 126 formal interviews of 97 employees, who all denied leaking the opinion, according to her report. In addition to the nine justices, 82 employees had access to either electronic or hard copies of the draft.

The marshal's investigation focused on "court personnel," including permanent employees and law clerks who work for the justices for a term. On Thursday, it was unclear whether the justices themselves were interviewed.

But on Friday, in response to questions from reporters, Curley released a statement that said she had spoken "with each of the Justices, several on multiple occasions." She said they "actively cooperated." Curley went on to say that she "followed up on all credible leads, none of which implicated the Justices or their spouses." And because of this, she concluded it wasn't necessary to have them sign sworn affidavits.

"Investigators continue to review and process some electronic data that has been collected and a few other inquiries remain pending. To the extent that additional investigation yields new evidence or leads, the investigators will pursue them," Curley said Thursday in her report. "If a Court employee disclosed the draft opinion, that person brazenly violated a system that was built fundamentally on trust with limited safeguards to regulate and constrain access to very sensitive information."

She lamented that the COVID-19 pandemic, which eased the ability to work from home, and gaps in the Supreme Court's security policies created an environment that made it easy to remove "sensitive information" from the building and the court's IT networks, raising the risk of "deliberate and accidental disclosures of court-sensitive information."

As part of its examination involving the court's computer systems, the investigative team focused on whether the draft opinion was moved electronically from the IT system before the publication by Politico. It also collected court-issued laptops and cellphones for personnel who had access to the draft opinion, though investigators to date have found "no relevant information" from the devices, according to the marshal's report.

Call and text logs retrieved by investigators also failed to yield anything relevant.

The document was first emailed to a distribution list of law clerks and permanent personnel on Feb. 10. Hard copies of the draft opinion were also given to some chambers, and 34 employees confirmed they printed out copies of the document. Many printed out more than one copy, according to the marshal's report, and several people acknowledged they "did not treat information relating to the draft opinion consistent with the court's confidentiality policies."

While investigators found certain employees emailed the document to other employees, they did so with approval and there was "no evidence discovered" that anyone emailed the draft to anyone else, according to the report.

For initial interviews conducted with nearly 100 court personnel, investigators reviewed legal research history to determine whether an employee may have researched the legality of disclosing confidential information relating to cases, but found nothing "suspicious or relevant" in the records obtained from internet service providers.

Employees who participated in initial interviews were also asked to sign sworn affidavits affirming that he or she did not disclose the draft opinion. Each of them did so, though "a few" who were interviewed admitted to telling their spouses or partners about the document or vote count, in violation of the Supreme Court's confidentiality rules.

"The interviews provided very few leads concerning who may have publicly disclosed the document," the marshal found. "Very few of the individuals interviewed were willing to speculate on how the disclosure could have occurred or who might have been involved."

Curley, though, said some court employees handled the document "in ways that deviated from their standard process for handling draft opinions."

In addition to examining "statements and conduct" of court personnel who "displayed attributes associated with inside-threat behavior," the investigators looked into connections between employees and reporters, including contact with anyone with ties to Politico and speculation on social media, some of which named law clerks. The investigative team, however, "found nothing to substantiate any of the social media allegations regarding the disclosure," according to the report.

The team also sought outside technical assistance on several matters, including a fingerprint analysis of an unidentified "item relevant to the investigation."

"That analysis found viable fingerprints but no matches to any fingerprints of interest," the report stated.

In the eight months since Politico published the draft opinion, no one has confessed to the unauthorized disclosure, and the marshal said investigators cannot rule out the possibility that the document was "inadvertently or negligently disclosed," such as being left in a public space either inside the court or outside.

Curley made a number of recommendations at the conclusion of her report, including that the distribution of sensitive court documents be limited and the use of hard copies "minimized and tightly controlled." She also advised the court to institute mechanisms to track the printing and copying of sensitive documents, and suggested consideration be given to supporting federal legislation prohibiting the disclosure of nonpublic case-related information.

In a two-page statement from Chertoff regarding his review of the marshal's investigation, he concluded Curley and investigators "undertook a thorough investigation within their legal authorities, and while there is not sufficient evidence at present for prosecution or other legal action, there were important insights gleaned from the investigation that can be acted upon to avoid future incidents."

Publication by Politico of the draft opinion overturning Roe, the landmark 1973 case that legalized abortion nationwide, marked a shocking breach of an institution known for the secrecy of its internal deliberations.

The possibility of the high court dismantling the constitutional protection for abortion rights sparked protests around the country and outside the Supreme Court. A large fence was erected around the court building as the demonstrations erupted, and protesters also marched outside the homes of the court's conservative justices in opposition to the draft opinion.

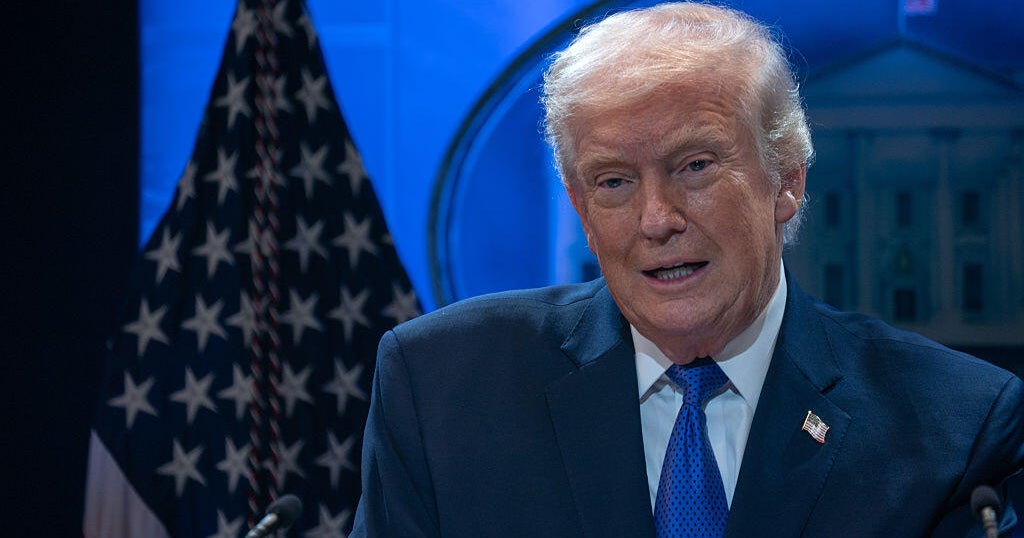

The Supreme Court quickly confirmed the document's authenticity. More than a month after the disclosure, the court released its final opinion in the case Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization. Five of the justices, including three appointed by former President Donald Trump, voted to overturn Roe.

Read the court's full report here: