Supreme Court justices question role of judges in partisan redistricting cases

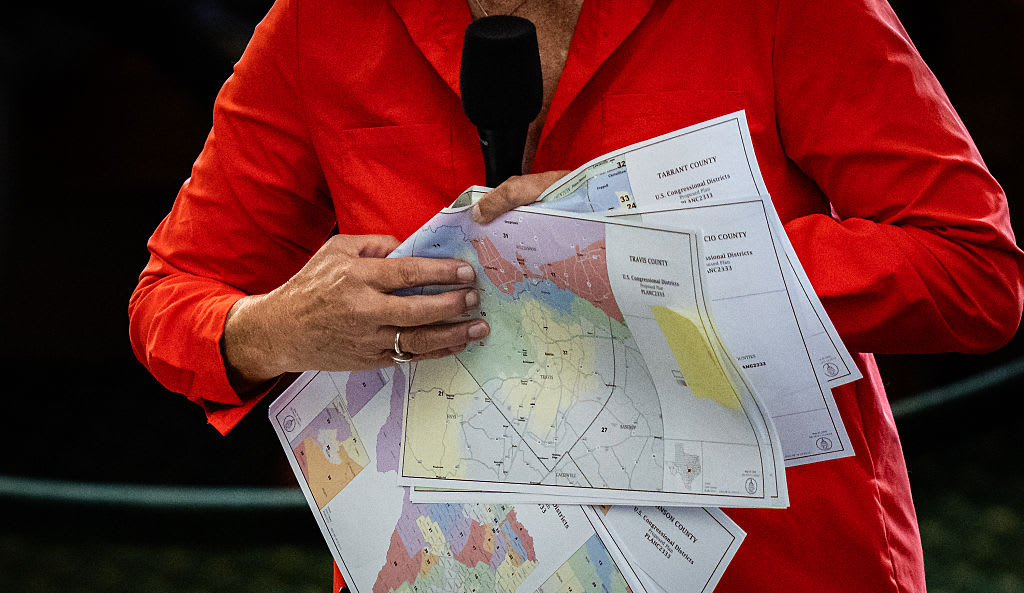

The Supreme Court's conservative majority seemed wary Tuesday of getting federal judges involved in determining when electoral district maps are too partisan. In more than two hours of arguments over Republican-drawn congressional districts in North Carolina and a single congressional district drawn to benefit Democrats in Maryland, the justices on the right side of the court asked repeatedly whether unelected judges should police the partisan actions of elected officials.

"Why should we wade into this?" Justice Neil Gorusch asked.

Gorsuch and Justice Brett Kavanaugh pointed out that voters in some states and state courts in others are imposing limits on how far politicians can go in designing districts that maximize one party's advantage. In light of activity at the state level, Kavanaugh asked if the country had reached the point where "this court and this court alone" must act.

But there was no certainty that the justices would, in the end, shut courthouse doors to claims over excessive partisan gerrymandering, as the practice of designing districts for political gain is known.

Kavanaugh, in particular, said he would not dispute the "problems of extreme partisan gerrymandering."

The cases at the high court marked the second time in consecutive terms the justices are trying to determine if they can set limits on partisan map-making. The court also could rule that federal judges should not oversee disputes over districts designed to benefit one political party.

Democrats and Republicans eagerly await the outcome of cases from Maryland and North Carolina because a new round of redistricting will follow the 2020 census, and the decision could help shape the makeup of Congress and state legislatures over the next decade.

Last year, the court essentially punted on cases from Wisconsin and the same Maryland congressional district that was before the court Tuesday.

Partisan gerrymandering is almost as old as the United States. While the court ruled 30 years ago that courts could police overly partisan map-making, the justices have never struck down districts on the ground that they violated the rights of voters from the minority party.

Supporters of limits on partisan redistricting say that it's more urgent than ever for the court to intervene because partisan maps deepen stark political division in the United States and sophisticated computer programs allow map-makers to target voters on a house-by-house basis.

They were disappointed last year when Justice Anthony Kennedy, who was open to reining in maps drawn for partisan ends, didn't join the court's four more liberal justices.

Defenders of the maps that are being challenged want the court to defer to the other branches of government and bow out of partisan districting cases. Their chances may have been strengthened by Kennedy's retirement.

Complaints about partisan gerrymandering almost always arise when one party controls the redistricting process and has the ability to maximize the seats it holds in a state legislature or its state's congressional delegation.

That's what happened in North Carolina, where Democrats hold only three of 13 congressional districts in a state that tends to have closely decided statewide elections. North Carolina has set the dates for their new election in the 9th Congressional District, just weeks after the North Carolina State Board of Elections held a dramatic hearing into allegations of ballot fraud in that race. The primaries will now take place May 14, with a general election slated for Sept. 10.

Republicans drew congressional districts that packed Democratic voters into the three districts that translated into landslide victories. Meanwhile, the map produced smaller winning margins for Republican candidates, but in more districts.

In Maryland, Democrats who controlled redistricting in 2011 wanted to increase their 6-2 edge in congressional seats. So they drew a map that would flip to Democrats a western Maryland district where a Republican incumbent served for 20 years.

Lower courts in both states struck down the districts as unconstitutionally partisan.

And the governors of both states also are urging the Supreme Court to "end gerrymandering once and for all."

Since the maps were drawn, North Carolina has elected a Democratic governor, Roy Cooper, and Maryland now has a Republican chief executive, Larry Hogan.

"The Supreme Court will soon hear arguments over whether politicians can be trusted to draw up their own districts. Take it from us: They can't," the governors wrote in an article published Monday in The Washington Post.

Decisions in Rucho v. Common Cause, 18-422, and Lamone v. Benisek, 18-726, are expected by late June.