Supreme Court could reel in power of federal agencies with dual fights over fishing rule

Washington — They can be pickled, smoked or used for bait, but on Wednesday, the silvery, skinny fish known as the herring will be the focus of a dispute that could end with the U.S. Supreme Court reeling in the ability of federal agencies to regulate the environment, health care and the workplace.

Underpinning the legal fight is a 40-year-old decision that, if wiped away by the court's expanded conservative majority, could diminish the so-called administrative state, long a goal of the conservative legal movement.

Known as "Chevron deference," after a landmark 1984 ruling involving the oil and gas giant, the longstanding doctrine requires courts to defer to an agency's reasonable interpretation of ambiguous laws passed by Congress. Critics of the framework argue it gives federal bureaucrats too much power in crafting regulations that affect major swaths of American life.

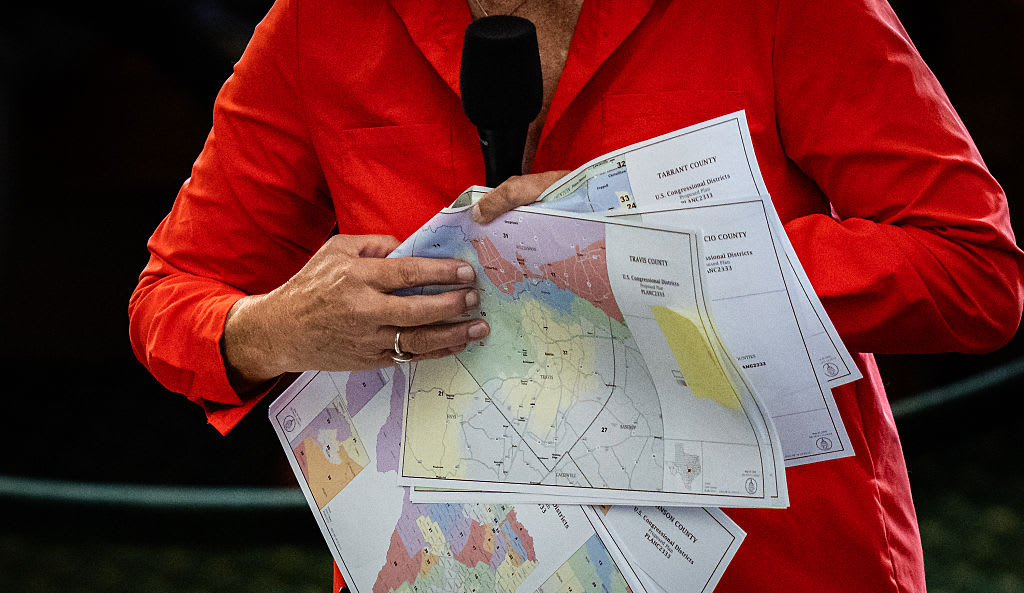

On Wednesday, the court will hear a pair of challenges to a 2020 regulation that required fishermen in the Atlantic herring fishery to pay for monitors who collect data and oversee operations while they're at sea.

The regulation

Fishing vessels have taken federal observers on trips for decades. But under the program enacted by the National Marine Fisheries Service during the Trump administration, they had to foot the bill for monitoring, which cost more than $700 per day, according to government estimates. The agency implemented the regulation under a 1976 law.

But to the fishermen, the government mandating they pay for at-sea monitors is like a town requiring residents to foot the bill for a police officer who rides in their cars and issues them speeding tickets, according to Meghan Lapp, the fisheries liaison for Seafreeze. The company operates two vessels, F/V Relentless and F/V Persistence, in the Atlantic herring fishery.

"This is inherently a government function, and we have no problem with taking the observers as required by Congress," she said. "But Congress did not require us to pay for them, and that is a huge distinction."

Seafreeze's style of fishing allows its vessels to remain at sea longer than others, typically 10 to 14 days, and they have the flexibility to target other species, like mackerel or squid, in addition to herring. But the regulation means that they may be on the hook for the federal monitor, even if they catch little to no herring. If they choose to leave the dock without a monitor and one is required, they can't fish for herring on that trip.

"It can push us out of this fishery," she said. "We've done it by the law, sustainably, the whole nine yards. But we're basically getting financially excluded from this fishery unless we want to be paying for a herring program out of the proceeds of other species. This makes going herring fishing or having that option financially prohibitive."

The fishermen go to court

The program enacted by the National Marine Fisheries Service, part of the Commerce Department, aims to have federal observers, who collect data needed for the conservation and management of the fishery, on 50% of trips by licensed vessels in the Atlantic herring fishery. But if there aren't enough government-funded observers to meet that target, the National Marine Fisheries Service can decide to waive monitoring for a trip or require an industry-funded monitor to fill the gap.

One month after the rule was finalized by the federal government, Seafreeze sued the service, alleging the agency did not have the authority to mandate industry-funded monitoring.

A federal district court in Rhode Island ruled for the federal government, applying a two-step framework under Chevron deference.

U.S. District Judge William Smith concluded in September 2021 that under the first step of the Chevron analysis, the federal law underlying the new monitoring rule was ambiguous. He also concluded that the National Marine Fisheries Service's decision to require fishermen to pay for the observers was allowed.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit upheld the lower court's decision, determining that the 2020 rule was a "permissible exercise of the agency's authority" under Chevron and was lawful.

The case in Rhode Island is similar to a separate dispute brought in the federal district court in Washington, D.C., in February 2020 by four commercial fishing companies in New Jersey that participate in the Atlantic herring fishery.

In that case, a district court concluded that the 1976 law unambiguously gives broad authority to the National Marine Fisheries Service to create regulations that are necessary to carry out conservation and fishery management measures.

A divided three-judge panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit concluded that the statute is not "wholly unambiguous" on whether the government can require vessels to pay for at-sea monitoring, and proceeded to step two of the Chevron framework. It then determined that the fisheries service's interpretation of the law is a "reasonable" way of addressing the "silence on the issue of cost of at-sea monitoring" and deferred to the agency.

The case brought in Washington arrived at the Supreme Court first, and the justices agreed in May that they would decide whether to overrule Chevron or clarify the framework. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson recused herself from the case, since she was on the three-judge panel that heard oral argument before the D.C. Circuit.

Several months later, in October, the high court agreed to review the 1st Circuit's decision. All nine justices will participate in that case.

The industry-funded monitoring program was suspended in April 2023 due to a lack of federal funding, and the fishermen were reimbursed.

Chevron deference and the Supreme Court

The concept of Chevron deference stemmed from the Supreme Court's 1984 landmark decision in the case Chevron v. National Resources Defense Council, which involved a regulation promulgated by the Environmental Protection Agency under the Clear Air Act.

Since then, Chevron has been applied by lower courts in thousands of cases. The Supreme Court has invoked it to uphold agencies' interpretations of statutes at least 70 times, though not since 2016.

Many in the conservative legal movement have for years called for the 40-year-old precedent to be overruled, arguing that it violates due process and contravenes the duty of federal judges to apply their independent judgment when evaluating federal statutes.

"What happens under Chevron, at least in these administrative law cases, is that the judge is forced to pre-commit to putting a thumb on the scale in favor of the government's interpretation of the law," said Mark Chenoweth, president and chief legal officer of the New Civil Liberties Alliance. "And that doesn't happen anywhere else, really, in our system — that you walk into court knowing that even if the judge thinks you have the better interpretation of the statute than the agency does, you still lose, as long as the judge thinks that the agency's interpretation is also reasonable. And that's just not consistent with due process of law."

The New Civil Liberties Alliance, backed by conservative donors, brought the Rhode Island case on behalf of Seafreeze.

But proponents of agency deference have warned that overturning Chevron would threaten agencies' ability to craft regulations on areas like the environment, nuclear energy or health care, and make it harder to implement laws that Congress has passed.

"I don't think it's an exaggeration to say that what is at stake in these cases is the continued viability of the administrative state and of the government to govern," said Clare Pastore, a law professor at the University of Southern California. "The question here is at what level of specificity does Congress have to spell out what it wants or needs."

Pastore, who worked for more than 20 years as a staff attorney of a public-interest law firm, acknowledged that Chevron deference "loads the dice in the agency's favor." But she said she worried that if the Supreme Court ends the doctrine, it will not replace it with a standard that still allows deference in some circumstances.

"Abandoning Chevron could lead to the court itself taking more power to make decisions. I'm also worried the court would simply say this regulation is invalid and leave us with a void, or worse yet, say Congress must address this and the agency can't act until Congress does, knowing full well that it is impossible for Congress to address every ambiguity in every statute," she said, noting that such a move "could grind the whole administrative state to a halt."

To some degree, Pastore said, "it's a question of, do you trust agencies more or do you trust courts more? Sometimes the answer to that is, it depends on who is the court and who is the agency."

The Biden administration has argued that Chevron is a "bedrock principle of administrative law" and "gives appropriate weight to the expertise, often of a scientific or technical nature, that federal agencies can bring to bear in interpreting federal statutes."

"Chevron has been invoked in thousands of decisions to uphold an agency's reasonable interpretation of a statute," Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar wrote in a Supreme Court filing in the Rhode Island case. "Private parties have ordered their affairs in reasonable reliance on that settled body of law, making investment decisions and entering into contracts informed by agency interpretations upheld under Chevron. Overruling Chevron would thus create 'an upheaval.'"

But Chenoweth, who worked at the Consumer Product Safety Commission, said that the notion that judges can't handle the complexity of cases where Chevron is invoked is "just wrong."

"Most of the time, these administrative law cases boil down to statutory interpretation, which is the expertise of judges, not the expertise of the executive branch," he said.

The court has in its last two terms shown that it is not hesitant to wipe away longstanding precedents. The justices reversed the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that established the constitutional right to abortion in June 2022, and ended the use of race as a factor in college admissions last year.

Additionally, Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch have in recent years suggested it's time to do away with Chevron doctrine.

"At this late hour, the whole project deserves a tombstone no one can miss," Gorsuch wrote in a November 2022 dissent. "We should acknowledge forthrightly that Chevron did not undo, and could not have undone, the judicial duty to provide an independent judgment of the law's meaning in the cases that come before the nation's courts. Someday soon I hope we might."

A decision from the court is expected by the summer.