NASA probe is the first spacecraft to ever enter the sun's atmosphere

NASA's Parker Solar Probe has survived a three year journey and a roughly 2 million degree Fahrenheit environment to do what was previously thought impossible: enter the sun's atmosphere.

The Parker Solar Probe launched in 2018. It has now circled the sun more than eight times and "touched" the sun for the first time when it entered the corona — the low density, high temperature upper atmosphere of the sun — in April 2021, according to data published in Physical Review Letters on Tuesday.

The probe's mission was to learn more about solar winds, which consist of streams of particles that influence the earth as well as magnetic zig-zags called switchbacks, and the sun's surface temperature.

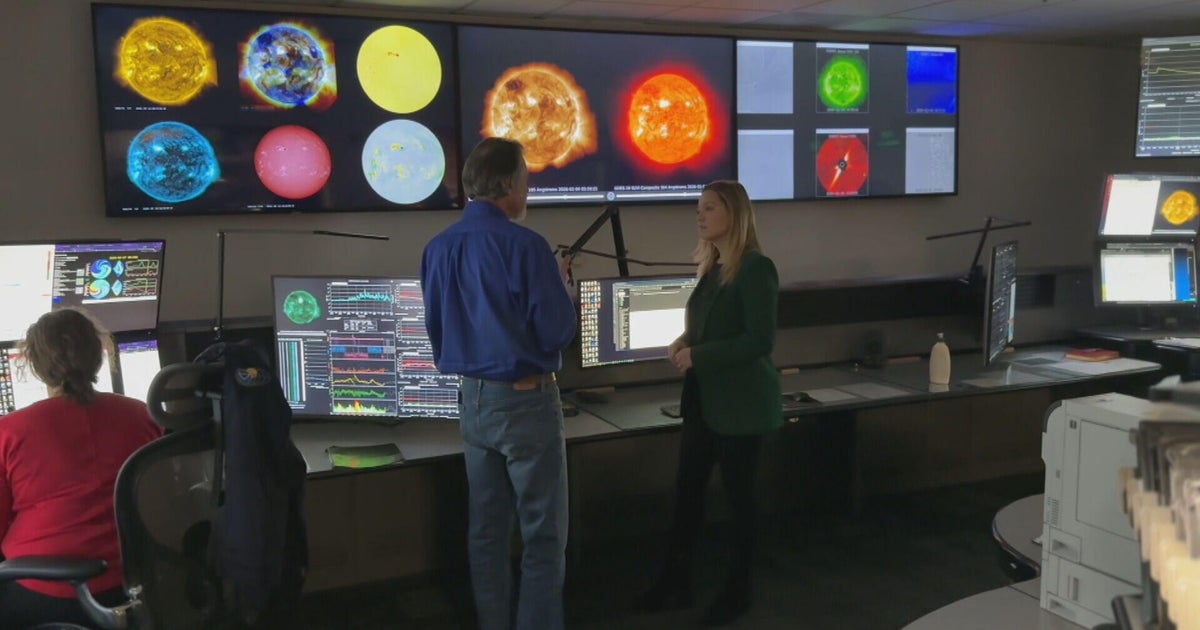

The achievement was the result of a massive collaboration between NASA and Harvard University and the Smithsonian's Center for Astrophysics. The Center for Astrophysics constructed the Solar Probe Cup, a part onboard the spacecraft that collected sample particles from the sun's atmosphere to confirm that it officially entered the corona.

"Parker Solar Probe 'touching the Sun' is a monumental moment for solar science and a truly remarkable feat," Thomas Zurbuchen, the associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington, said in a NASA press release. "Not only does this milestone provide us with deeper insights into our Sun's evolution and its impacts on our solar system, but everything we learn about our own star also teaches us more about stars in the rest of the universe."

During its travels to the sun, the probe discovered the solar winds' switchbacks became more frequent close to the sun. But researchers didn't know how these switchbacks were formed. Once they arrived at the sun's corona, researchers discovered that the switchbacks likely formed in magnetic funnels near the sun's surface, but how they form remains unknown.

Researchers are hopeful that they will learn more about how and where solar winds are formed as well. In Tuesday's publishings, researchers hypothesized that parts of solar winds may be forming in the sun's magnetic funnels.

If these questions are answered, researchers may be able to understand why the corona is millions of degrees hotter than the sun's surface.

"My instinct is, as we go deeper into the mission and lower and closer to the Sun, we're going to learn more about how magnetic funnels are connected to the switchbacks," Stuart Bale, professor at the University of California, Berkeley said. "And hopefully resolve the question of what process makes them."

The probe also found that the surface of the corona isn't smooth, as some researchers originally predicted. When the probe approached the sun's atmosphere, it went in and out of it several times, leading researchers to conclude it has "spikes and valleys" that "wrinkle the surface."

Solar atmosphere studies are "a really important region to get into because we think all sorts of physics potentially turn on," Justin Kasper, lead author and deputy chief technology officer at BWX Technologies, Inc. and a University of Michigan professor said. "And now we're getting into that region and hopefully going to start seeing some of these physics and behaviors."

Next, the solar probe will spiral closer to the sun and hopefully reach a distance of around 4 million miles from the surface. The probe will reenter the atmosphere in January 2022.