The subpoena war between the White House and Capitol Hill is only getting started

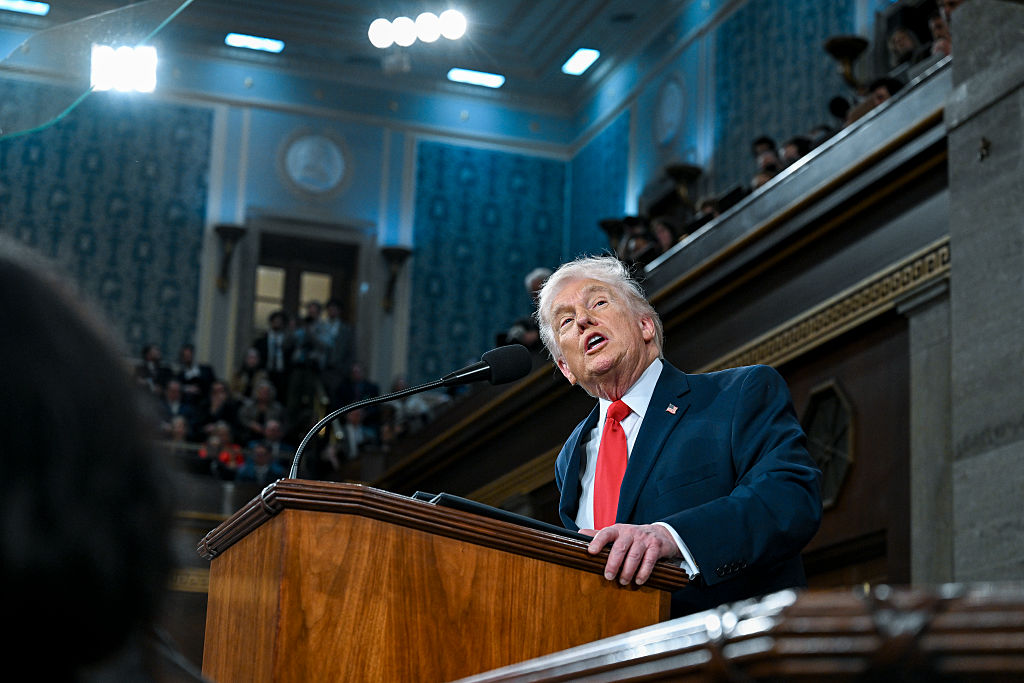

President Trump made it clear that he does not want his aides testifying before Congress, as his administration shoots down subpoenas for current and former officials to appear before Congress.

"There is no reason to go any further, and especially in Congress where it's very partisan — obviously very partisan," the president told the Washington Post, telling reporters later, "We're fighting all the subpoenas."

With the battle lines drawn between Capitol Hill and the White House, the question becomes whether the White House can successfully invoke executive privilege in each various case. Here are the various people in the president's orbit whom Congress has subpoenaed — or will likely subpoena.

Don McGahn, former White House counsel

Subpoenaed to appear before House Judiciary Committee regarding Mueller report

Former White House counsel Don McGahn — a prominent figure in special counsel Robert Mueller's report who defied the president's demand to oust Mueller, as well as Mr. Trump's subsequent order that he deny that Mr. Trump tried to fire Mueller — has been subpoenaed to testify before the House Judiciary Committee. But the White House says all options are on the table in considering whether to invoke executive privilege and prevent him from testifying, and McGahn hasn't said whether he will appear or not. Mr. Trump has been contradicting Mueller's report, claiming he never directed McGahn to fire the special counsel.

It's unlikely the White House can prevent McGahn from showing up entirely, especially since McGahn no longer works for the White House. But it is weighing whether to invoke executive privilege.

John Bies, counsel for the government transparency group American Oversight, who served as counsel to former Attorney General Eric Holder, said much depends on whether or not McGahn wants to appear before Congress.

"I think that depends some on the circumstances, and I don't think we know yet whether Don Mcgahn is inclined to testify," Bies said.

Whether the White House hampered its argument for executive privilege by allowing McGahn — and others — to testify before the special counsel is also up for debate, Bies said.

"I think it's hard for the president to say they have compelling confidentiality to protect in material that's already public," Bies added.

Typically, the strongest argument for executive privilege involves direct communications with the president, said Saikrishna Prakash, a law professor at the University of Virginia who clerked for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.

"The basic claim is that the president needs candid advice, and he can't get candid advice" if those conversations might be "spilled on the pages of the New York Times," Prakash said.

The White House could find it difficult to stop McGahn from testifying, if it turns out he wants to do so.

"What's interesting about McGahn and this is true for everybody — what can the president do if he wants to testify and reveal confidential information?" Prakash said.

Carl Kline, former White House personnel security director

Subpoenaed to appear before House Government Oversight and Reform Committee about White House security clearance process

The White House has also been attempting to block former White House Personnel Security Director Carl Kline from testifying, having instructed Kline not to show. Kline, who still works for the federal government as a Defense Department employee, failed to appear at a committee hearing on security clearances recently.

But the White House finally acquiesced to letting him testify in person.

Kline helped oversee the security clearance process in the White House, a process which has come under scrutiny ever since former White House aide Rob Porter was accused of abusing his former wives. Tricia Newbold, a current White House employee and whistleblower, claims Kline ignored concerns she voiced that the White House was granting security clearances against recommendations.

Cummings had threatened to schedule a vote to hold Kline in contempt of Congress, although being held in contempt of Congress doesn't carry any legal weight.

Generally speaking, Bies noted that a current government official like Kline or anyone else would be more likely to comply with the administration's wishes than would a private citizen.

John Gore, principal deputy assistant attorney general for Justice Department civil rights deposition

Subpoenaed to appear before House Government Oversight and Reform Committee about 2020 Census citizenship question

Attorney General William Barr is also blocking John Gore, the principal deputy assistant attorney general for the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division, from testifying before Congress. The House Oversight and Reform Committee subpoenaed Gore to testify about the citizenship question the administration intends to place on the 2020 Census, an issue the Supreme Court has agreed to take up this year.

In Gore's case, the Justice Department wants to allow its attorneys in the same room as Gore. The committee is allowing a Justice Department attorney to sit in another room, where Gore could go back and forth with questions for advice.

"This is just form over substance," Prakash said.

At the end of the day, Bies noted, it's going to be tough for the administration to argue in Gore's case or anyone else's that it can block Congress from hearing from a current official with specific jurisdiction over an issue.

Stephen Miller, senior policy adviser to the president

Has been asked to appear before House Oversight and Reform Committee about immigration crackdown and overhaul of Homeland security

Stephen Miller, the president's senior policy aide who is behind Mr. Trump's overhaul of the Department of Homeland Security and immigration crackdown, hasn't been subpoenaed — yet. But the White House has rejected a request from House Oversight and Reform Committee Chairman Elijah Cummings to allow him to testify.

White House lawyers might have the best shot at preventing Miller from testifying, given that Miller is a current White House employee who is not a Senate-confirmed official. A 1999 DOJ Office of Legal Counsel opinion noted that "the president and his immediate advisers are absolutely immune from testimonial compulsion by a congressional committee."

"There are arguments that certain, very senior officials in the White House are difficult to call to the hill to testify," Bies noted.

What the precedents say

There are few court cases that provide precedent for any litigation over the the executive branch's desire to stop current or former officials from testifying.

A 2008 D.C. District Court decision found that former White House counsel Harriet Miers and White House chief of staff Joshua Bolten had to cooperate with a House Judiciary Committee investigation into allegations of misconduct within the Justice Department.

In 2012, Attorney General Eric Holder cited executive privilege in refusing to turn over to Congress documents related to a failed operation to stop gun trafficking, called Operation Fast and Furious. The House, under GOP control, voted to hold him in criminal and civil contempt. Though a federal judge ruled that he should not be held in contempt of court, Holder was ordered to turn over some documents are records in the case, but did not ultimately release the records until late 2018, after a six-year-long legal battle and several more orders by the judge in the case to do so. In May, seven years after Holder asserted the privilege, the Justice Department announced a settlement agreement over a contempt of Congress case against the former attorney general.

Bies, who was counsel to Holder over the "Fast and Furious" operation, argued that a key difference between Holder declining to hand over all records related to that probe and the Trump administration's refusal is the Trump administration is issuing blanket refusals to show up to testify or hand over information. The "Fast and Furious" operation involved Phoenix employees of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms allowing illegal gun sales in order to track targets.

Back then, Republicans were outraged at the Obama administration for not handing over all records, even as Republicans now balk against Democratic committee chairmen's demands that officials testify.

Bies said the months ahead mark an "important constitutional moment," if the Trump administration continues to uniformly block officials from even appearing before Congress.

One thing is for sure — this is going to be a long, drawn-out process, Prakash said: "I do think it's going to take forever and that of course plays to the executive branch's hand."