How one woman shed $350,000 in student loans — without a lawyer

From the moment she moved to Los Angeles for graduate school, Mis Loe found herself living what she describes as always being "one paycheck behind."

The aspiring film producer had enrolled at the prestigious American Film Institute Conservatory in 2016, taking out loans to cover the more than $200,000 tuition cost, while working at a coffee shop and driving for Postmates to cover her living expenses. But despite working full-time hours, her monthly pay came in just below her expenses — $1,500 monthly rent, $800 for medication, $300 in car payments. Loe found herself falling further behind every month, putting daily needs like food and rent on her credit card.

"I was living off one overdraft," Loe, now 47, told CBS MoneyWatch. "I had to use every hour I had to create money." Still, the bills snowballed. And when the coronavirus struck in spring 2020 and shut down all three of her jobs, "the snowball hit me in the face," she said.

Loe filed for bankruptcy that spring, with $410,000 in debt and her income down to $200 in weekly unemployment benefits. She wasn't optimistic: Most of her debt was in student loans, which between undergraduate and graduate schooling had ballooned to $350,000. Like most Americans, she assumed student debt was bankruptcy-proof, and the few lawyers who took her calls told her the same thing, Loe said.

Still, after reading a Facebook post from another indebted college graduate, she decided to fight. She sued the Department of Education last August, claiming that repaying her loans would be impossible given her financial and medical condition.

After a year of legal wrangling, her case settled this month, with Loe agreeing to pay just $7,200 over 10 years. Her first payment is due October 1.

"I want to move forward now with my life," Loe said. "It's a 10-year deal — the sooner I start, the sooner it'll be over."

"It's a very high success rate"

"I have never seen $350,000 of debt being discharged," said Rohan Pavuluri. "You can imagine why people don't even try."

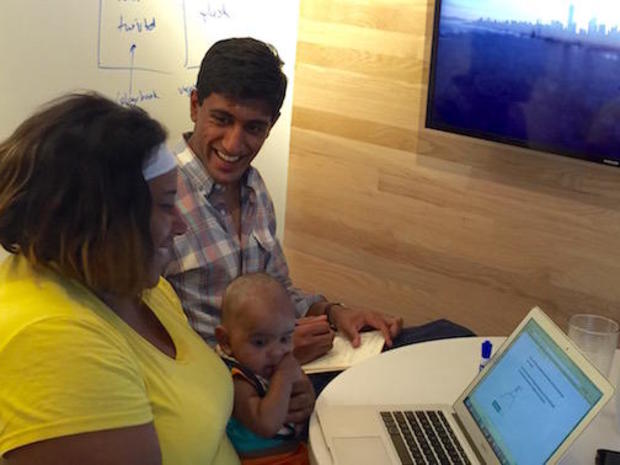

Pavuluri is the CEO of Upsolve, a nonprofit organization that helps people file for bankruptcy for free. Loe used Upsolve's app to file her initial case, and she is now pushing for the company to expand its services to help people like her file their own student loan discharge.

Although the amount of Loe's debt makes her case unusual, her success in having it discharged isn't as rare as many believe. In fact, student debtors who try to wipe out education loans in bankruptcy tend to succeed more than half the time, according to research from Jason Iuliano, a law professor at the University of Utah.

In 2017, 447 debtors tried to get student loans cleared in bankruptcy, Iuliano noted in a recent paper. Of those, 234 — nearly 60% — either won the case or settled with their creditors.

"It's a very high success rate once you actually go before the judge and say, 'I deserve a discharge,'" Iuliano told CBS MoneyWatch.

The larger issue, said Iuliano, is that most people don't even try. While about a quarter of a million people with student loans file for bankruptcy each year, only a few hundred take the extra step of filing an adversary proceeding to try to clear their student debt — because most believe it's impossible.

"[E]very year, tens of thousands of bankrupt debtors miss out on obtaining a student loan discharge simply because they fail to request one," he wrote.

Proving "undue hardship"

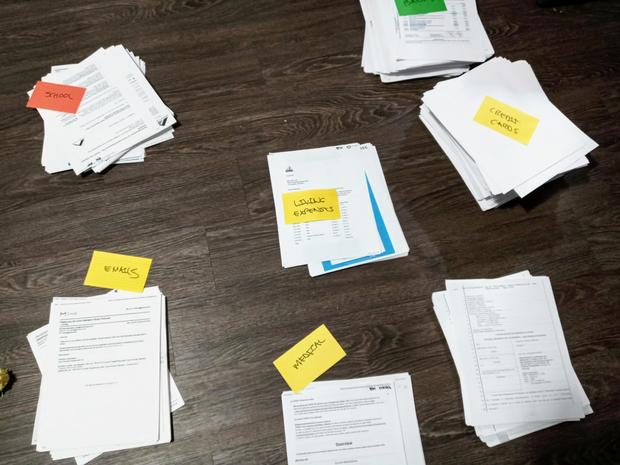

For most families, bankruptcy is largely an exercise in filling out forms, said Pavuluri of Upsolve. Individuals list debts and assets, attend a court hearing and then see most of their debts cleared.

Student loans require extra steps. A debtor has to actively sue their creditor by filing what's called an adversary proceeding. The bankruptcy then proceeds like a more typical lawsuit, with both sides presenting evidence, calling witnesses and testifying in court. What's more, the indebted grad often needs to prove that paying back the loan would create an "undue hardship" — a standard that is vague and difficult to meet, as each court interprets it differently.

The process is daunting for debtors and lawyers alike. "Most attorneys won't take these cases on," said Iuliano, "even if you go to an attorney and offer to pay them upfront."

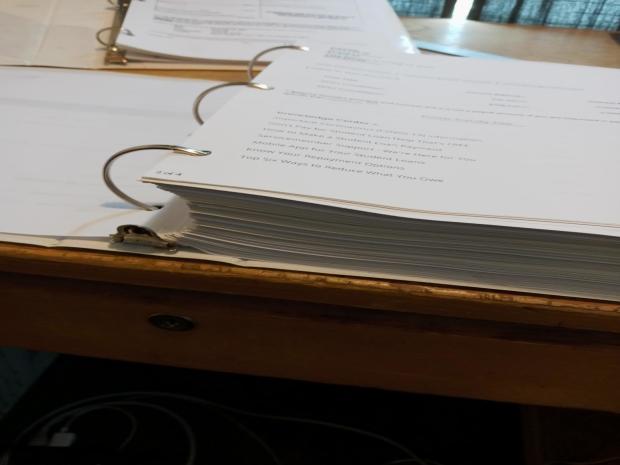

Loe spent several weeks calling around to legal-aid organizations only to be told they couldn't help. One attorney who specialized in student loan discharge offered to advise Loe for $2,000. But for Loe — who bought a home printer to file her bankruptcy because she couldn't afford an $800 printing charge at Staples — that fee was out of reach. So she pulled up hundreds of student debt cases and read judgments last summer in a process that she estimates took 1,000 hours. In August, she sued the Department of Education in a complaint that ran 180 pages.

"I gave them everything," she said. "There was no way I was going to file this and not prove it in every way possible."

Her complaint describes in minute detail the costs she has had to pay since she was an undergraduate. Diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in the mid-1990s, she spent years in and out of the hospital before finding a job, as a manager at a coffee shop, that offered her health insurance. With full-time work her new priority, schooling took a back seat. After several starts and stops, Loe finally received her bachelor's degree in 2013 — 21 years after she began.

The following year, the coffee shop closed and she was laid off, leading her to move to Los Angeles to pursue filmmaking. During that time, she deferred her loans a half-dozen times and received 12 forbearances. She also went on several income-driven repayment plans, which typically offer the borrower a smaller monthly payment. But even those plans proved too much for her to pay, Loe said, because the salary-based calculations did not account for her medical costs, which approached $800 a month.

"I have always worked hard," Loe said. I have always worked more than 40 hours a week, and often two or more jobs at a time."

"The whole point of my case was to show if I have health insurance, if I have medicine, I can be healthy and productive. I cannot afford to take care of myself given my current financial situation," she said.

Leading up to her court date, Loe had several fruitless exchanges with the Department of Education in which she tried and failed to come to an agreement. She was prepared to put her fate in front of a judge, even though she had no guarantee a judge would rule in her favor. Then — a week before her scheduled court hearing — the Department of Education accepted her offer.

"It saved my life," Loe said. "It helped me out of a really horrible situation that I didn't know how I was going to get out of."

Broader push for student-debt relief

A handful of recent cases have poked holes in the argument that student debt is forever. Last year, 51-year-old Katy Adams won a discharge of $41,000 in student debt when the government's lawyers asked for the personal bankruptcy case to be dismissed before the judge could rule on whether she met the undue hardship standard.

A court in Nebraska relieved a 50-year-old grandmother of nearly $90,000 in debt, finding her prospects of finding higher-paying employment uncertain and her ability to continue working two jobs — due to health conditions and the needs of her autistic grandson in her care — unlikely. And a judge in Poughkeepsie, New York, made waves in a scathing opinion that cleared $220,000 of debt accrued by law school graduate and Navy veteran Kevin Rosenberg.

"[M]ost people (bankruptcy professionals as well as lay individuals) believe it impossible to discharge student loans," Judge Cecelia Morris wrote. "This Court will not participate in perpetuating those myths."

Amid a broader movement for student-debt relief, some Americans are pushing to make it easier to discharge old loans in bankruptcy. Senators Dick Durbin (D-Illinois) and John Cornyn (R-Texas) introduced a bill last month to include student loans older than 10 years in bankruptcy proceedings, and penalize schools if too many of their graduates go bankrupt.

"Bankruptcy is in the constitution. The founding fathers included it because they wanted people to have a fresh start, they didn't want people to be executed or go to jail," said Pavuluri of Upsolve. "That's what it means to participate in capitalism ... You fall down, you try and get up again."

Loe, too, is hoping for a change in the bankruptcy laws. Until that happens, she said, "the No. 1 thing for people to understand is to not pay attention to the statistics."

She added, "I want to change the narrative from 'This is something impossible' to 'You can try.'"