Voting during a pandemic? Here's what happened in 1918

In early March, while the remaining Democratic presidential contenders were sprinting across the country in search of primary victories, the COVID-19 pandemic was taking its own destructive path through the nation. States with upcoming primaries were forced by the novel virus to reconsider a question from a century ago about how to keep the public safe at the ballot box.

The last time a health emergency so imperiled American politics was in 1918, when the Spanish flu killed 675,000 Americans and was dubbed the "mother of all pandemics." The flu peaked in October and November that year, according to the American College of Emergency Physicians, just days before the midterm elections on November 5.

Unlike politicians today, who bring epidemiologists and doctors to their briefings, their predecessors 102 years ago were equipped with much less scientific insight. They were also running out of time to hold necessary elections, since Congress in 1845 mandated congressional elections on the first Tuesday of November.

Newspaper accounts reviewed by CBS News show states forged ahead with politics, even as campaigns across the country in 1918 were forced to hit pause on traditional campaigning.

In Louisville, campaigns were banned from public speaking because of the contagion, a decision the Twice A Week Messenger called "the most unusual situation that has ever been met with in a political campaign in this state as a result of the influenza epidemic."

"We are going to cooperate fully…and will call off all meetings scheduled where there is evidence of any danger whatever," Democratic Campaign Committee spokesman James Garnett told the paper.

To skirt similar gathering bans in Kansas, some campaigns in the state moved their speeches to outdoor churches. But once state health officials found out, those were quickly outlawed, too.

"Plans for different party organizations to whip things up…has gone 'bluey' owing to the flu," The Wichita Daily Eagle in Kansas wrote in October 1918, predicting voters could only expect "hot stuff" in the press from campaign "spellbinders," the more colorful term for surrogates.

In Wisconsin, candidates were "working quietly" with newspaper advertising and mailing campaign literature, since "politics in Wisconsin has been indefinitely adjourned by the epidemic of influenza," according to the Wisconsin State Journal on October 27, 1918.

One silver lining to the lighter campaign schedule? "Defeated candidates will probably blame the epidemic for their defeat, but they, as well as the successful ones will have saved hundreds if not thousands of dollars as the result of the epidemic," the Journal added.

As Election Day approached, activist groups relied on issues-based appeals to encourage voting, even as the pandemic spread.

Alcohol prohibition was on the ballot in at least eight states in 1918, and temperance activists like the Muskingum County Dry Federation in Ohio's The Times Recorder accused the liquor industry of trying to profit off the "suffering and deaths of human beings" because of the flu. "They are industriously circulating reports everywhere that whiskey is a cure for the great influenza epidemic," the group argued in the paper.

Prohibition opponents bought a full-page ad in Florida's The Tampa Times and declared, "liquor has saved many a life recently in this terrible epidemic of Influenza," citing reports of the use of liquor in "alcohol baths" for Iowa flu patients and as stimulants for sick military men in Camp Lee, Virginia.

Suffragists also hoped to draw supporters to the 1918 polls to build on the 12 states where women had already won the right to vote, according to the National Constitution Center. Even as some Louisiana newspapers warned about the grim flu statistics, the Shreveport Journal captured women suffragists organizing Election Day canvassing by foot and automobile. As the flu raged in Nevada, a state where women had been able to vote for four years, suffragists sought revenge at the polls. "Rebuke the Democratic Party!" one ad blared in the Reno Gazette Journal, blasting the conservative Democratic-majority in the U.S. Senate for not passing the national Suffrage Amendment earlier that year.

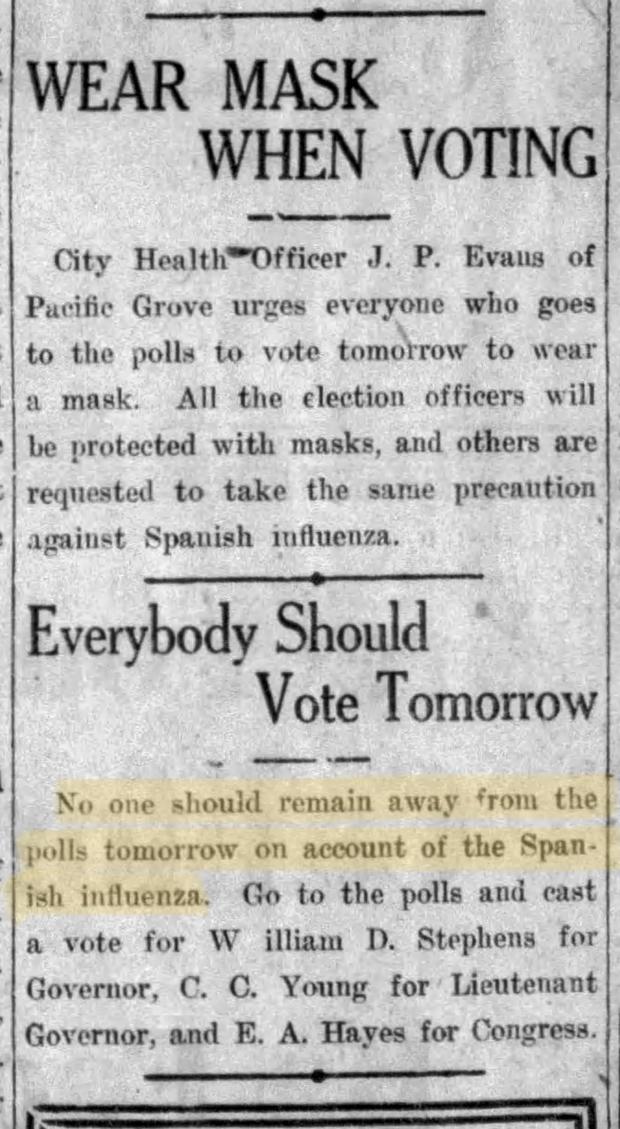

Other states turned to patriotism to get voters to the polls, arguing that voting in the face of the Spanish flu supported American soldiers in World War I. California experienced peak death rates, the Los Angeles Times front page said, declaring, "Every Loyal Californian Will Cast Vote at Election," just six days before the war's armistice.

But as Election Day grew closer, medical worries were placed ahead of political wins in some states. In North Dakota health authorities considered the "unheard of possibility of postponing the general election" due to more than 15,000 influenza cases, according to The Bismarck Tribune.

One Florida headline — "Flu vs. Ballot" — in the Tampa Times warned the virus was nonpartisan. "The candidates nominated in the Democratic primary are worrying very little about the outcome of the election…as the 'flu' is no respector of person and Republicans, socialist, independents, etc., have the disease just the same as the Democrats," the paper wrote.

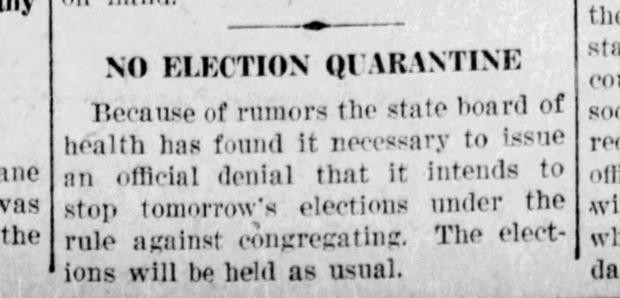

Other state officials soon clarified that the election would proceed.

"Because of rumors the state board of health has found it necessary to issue an official denial that it intends to stop tomorrow's elections under the rule against congregating," a bulletin in Wisconsin's Stevens Point Journal noted. "The elections will be held as usual."

The Marion Star in Ohio, too, promised the election would go on — "Flu Ban or No Flu Ban."

Election Day

"Social distancing" echoes can be seen in instructions that appeared in Fresno's 1918 voting guidelines, which urged "not congregating at the polls and avoiding needless exposure."

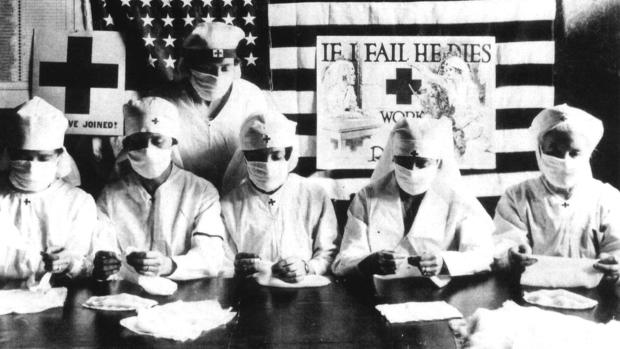

"Persons are advised to enter the polling places where enclosed, one or two at a time, and to exercise all sanitary precautions," and included the mandatory face masks in California, The Fresno Morning Republican stated. The San Francisco Chronicle wryly noted that it was "the first masked ballot ever known in the history of America."

Reports depicted California polling places as the "quietest within memory" and said they welcomed only the most ardent voters, like Nancy Elworthy, 92, who said while she was almost blind, she still believed voting was "the duty" of every citizen. It is unclear if Elworthy noticed either her fellow voters, described by poll workers as "confessedly suffering from influenza" or that the polling booths lacked spray and disinfectant, according to the Chronicle.

"I must get back to bed at once," one other voter told the paper upon exiting. "I really should not have come out to vote with this flu!"

New Mexicans were too "afraid of the flu" to vote, and Arizona polls had "light turnout" even with the state's promise to regularly disinfect polling booths, the El Paso Herald reported. The election was a "rather quiet one" in Minnesota, the Little Falls Herald reported, and in Utah, the Parowan Times diagnosed one cause of low turnout: "Many women who usually vote were unable to go to the polls because of being compelled to remain at home to care for the unwell."

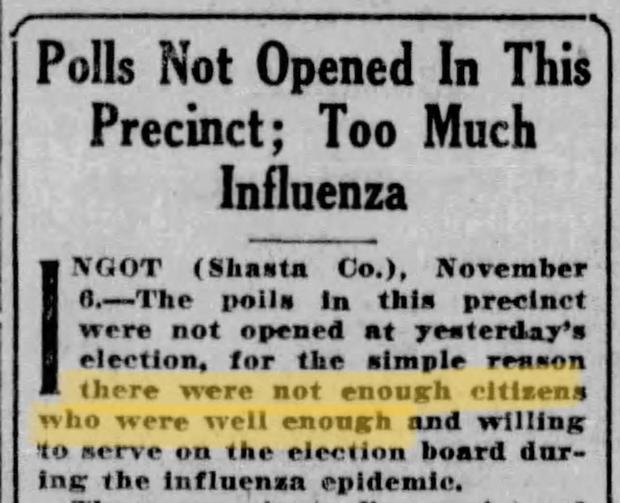

Some poll sites were unable to open due to "too much influenza," according The Sacramento Bee, declaring "there were not enough citizens who were well enough."

Several newsrooms were also forced to close because of quarantine laws. The Long Beach Press announced it was unable to report election results for the first time in its history and respectfully requested that readers not call to ask questions, since the telephone company's workforce was "weakened" due to sickness.

Voter turnout was lower than in the previous midterm elections. While World War I impacted the number of eligible voters, an analysis by Jason Marisam in the Election Law Journal found the flu had a "significant effect" on turnout.

"If just a fraction of the drop in turnout from 1914 to 1918 was due to the presence of the flu, then the disease was responsible for hundreds of thousands of people not voting," Marisam noted of the more than 10% decrease in voters.

The flu was used as scapegoat for congressional losses by the Republican National Chairman and prompted legal challenges in some communities, such as when a defeated North Dakota state legislative candidate asserted election officials had unfairly delivered ballots to houses in some districts and not others, according to the Grand Forks Herald.

Today, as American government leaders face another pandemic, historians recognize similar challenges for the federal government system now as it confronted during Spanish flu era.

"I think there is something of not absorbing the historical lessons that contributed to our delays and actions," Harvard University professor Alex Keyssar, who specializes in election history, told CBS News. "To be clear, it's not to say that everybody in the [Trump] administration should have been read up on the 1918 flu…but there should be some center of expertise which does absorb those historical lessons to whom policymakers turn."

Also, states mostly control their own elections, which has resulted in a patchwork across states of both emergency response and political decisions, Keyssar explained. As states stake their hopes on the relatively quick development of antiviral treatments in the next few months before the general election, most states that have yet to vote in primary elections are reluctant to risk increasing the spread of the virus.

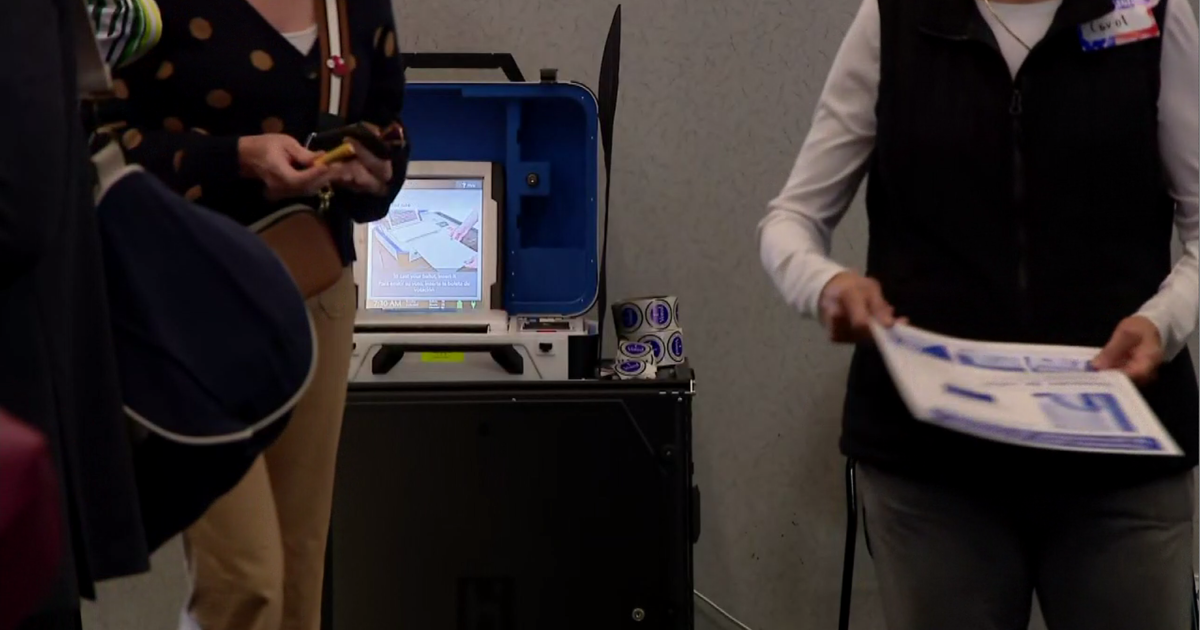

At this point, knowledge that COVID-19 is highly contagious and the belief that it has a higher mortality rate than the flu has convinced eleven states to postpone their presidential primaries, five states to expand absentee voting, and after a series of legal battles over the past few days, Wisconsin is pushing ahead with its in-person primary on Tuesday.

As some election officials did in 1918, Wisconsin has promised to disinfect polling booths and maintain social distancing.