SpaceX Crew Dragon chalks up picture-perfect space station docking

Nineteen hours after a spectacular Florida launch, SpaceX's Crew Dragon capsule caught up with the International Space Station early Sunday and glided in for a problem-free docking, bringing veteran astronauts Douglas Hurley and Robert Behnken to the outpost in SpaceX's first piloted space flight.

The historic mission marks a major milestone in NASA's push to end the agency's sole reliance on Russian Soyuz spacecraft for carrying astronauts to and from the lab complex, the first piloted launch to orbit by a privately owned and operated spacecraft since the dawn of the space age.

"Welcome to Bob and Doug," NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said to the crew in a call from mission control at the Johnson Space Center. "The whole world saw this mission, and we are so, so proud of everything you've done for our country and, in fact, to inspire the world."

"We sure appreciate that, sir," Hurley replied, floating in the space station's Harmony module, flanked by crewmate Behnken, space station commander Chris Cassidy and Russian cosmonauts Anatoly Ivanishin and Ivan Vagner.

"It's obviously been our honor to be just a small part of this," he said. "We have to give credit to SpaceX, the Commercial Crew Program and, of course, NASA. It's great to get the United States back in the crewed launch business, and we're just really glad to be on board this magnificent complex."

Following a picture-perfect climb to space Saturday atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, Hurley and Behnken monitored an automated rendezvous with the station Sunday, approaching the lab complex from behind and below.

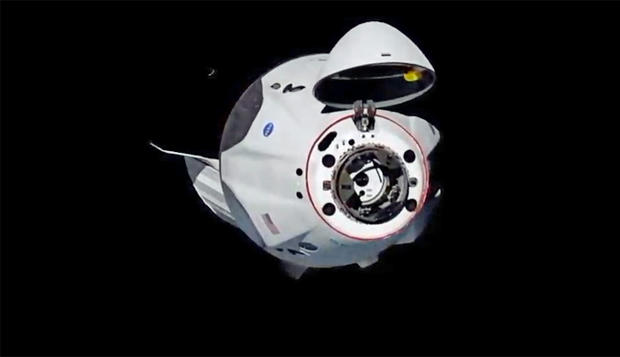

Executing a precise series of thruster firings, the Crew Dragon looped up to a point directly in front of the station and lined up on the lab's forward docking port, the same one once used by visiting space shuttles.

Hurley, a former Marine test pilot, briefly took over manual control, firing thrusters by tapping high-tech touch-screen cockpit displays to verify a crew's ability to fly the spacecraft by hand if needed.

The ship's flight computer than resumed the approach and the Crew Dragon's docking mechanism engaged its counterpart on the space station at 10:16 a.m. ET, about 15 minutes ahead of schedule. A few minutes later, the capsule was pulled in and locked in place by 12 motorized latches.

Cassidy, a former Navy SEAL, followed naval tradition and rang the ship's bell aboard the station to announce the Crew Dragon's arrival.

"Dragon, arriving," he said. "The crew of Expedition 63 is honored to welcome Dragon and the Commercial Crew Program to ... the International Space Station. Bob and Doug, glad to have you as part of the crew. Well done. Bravo zulu."

"We here at SpaceX are honored to have been part of ushering in this new era of human spaceflight," said Anna Menon, the spacecraft communicator at SpaceX's Hawthorne, California, control center. "On behalf of the SpaceX and NASA partnership, congratulations on a phenomenal accomplishment. And welcome to the International Space Station."

During the post-docking welcome aboard ceremony, Republican Senator Ted Cruz of Texas asked the Crew Dragon astronauts "how does she handle?"

"It flew just like it was supposed to," Hurley said. "We had a couple of opportunities to take it out for a spin, so to speak (flying manually), and my compliments to the folks back at Hawthorne and SpaceX for how well it flew. It's exactly like the simulator, and we couldn't be happier about the performance of the vehicle."

Representative Brian Babin, a Texas Republican who represents the Johnson Space Center, asked the astronauts to describe their impressions of launching atop a Falcon 9 rocket.

Behnken, who flew twice aboard the space shuttle, recalled a fairly rough ride on the orbit while its two solid-fuel boosters were firing, but a smooth ascent after that with the shuttle's three liquid-fueled engines.

He and Hurley expected the Falcon 9 ride to smooth out after the rocket's first stage, powered by nine engines and generating 1.7 million pounds of thrust, was jettisoned about two-and-a-half minutes into flight. The Falcon's second stage is powered by a single engine.

"We were surprised a little bit by how smooth things were off the pad," Behnken said. "The space shuttle was a pretty rough ride heading into orbit with the solid rocket boosters, and our expectation was as we continued with (our) flight into second stage, that things would basically get a lot smoother than the space shuttle.

"But Dragon was huffin' and puffin' all the way into orbit, and we were definitely riding a Dragon all the way up," he said. "So it was not quite the same ride, the smooth ride as the space shuttle was up to MECO [main engine cutoff], a little bit less Gs but a little bit more 'alive' is probably the best way I could describe it."

The Crew Dragon is expected to remain docked to the station for six weeks to four months, allowing Behnken and Hurley to help Cassidy with a full slate of NASA and partner agency research and, possibly, with one or more spacewalks to install new solar array batteries and complete installation of a European experiment platform.

Cassidy said he looked forward to the help.

"We've got a few things to take care of tonight, make sure we're all safe and we know the plan in case something bad happens," he said, referring to a standard emergency briefing given to all newly arrived crew members.

"And then we're looking forward to some operational stuff later in the month, maybe we'll get outside and do some spacewalks. So we're all super excited to have two more crewmates to the Expedition 63 team."

NASA originally planned a short one-week to 10-day test flight for the first piloted Crew Dragon. But delays in the agency's Commercial Crew Program and scaled-back production of Russian Soyuz spacecraft forced NASA to reduce the lab's U.S. and partner agency crew to just one — Cassidy.

NASA managers are holding off on making a decision on when the Crew Dragon will return to Earth until they get a better idea of how atomic oxygen in the extreme upper atmosphere might affect the capsule's solar cells.

No matter how that works out, engineers want time to thoroughly evaluate the capsule's performance before proceeding with the first operational flight. NASA and SpaceX hope to launch that flight, carrying an international three-man one-woman crew, in the late August timeframe.