South Africa still haunted by AIDS stigma

KWAZULU-NATAL, South Africa -- For AIDS hospice workers Francisca Dladla and Adelaide Mthembu, their daily ritual of singing the Lord's Prayer gives them strength as they make treks to reach their patients.

Zungezani Ngwazi is blind and widowed, and she's blunt about what would have happened if the hospice workers had not come to her mud hut.

"I would have died quite a long time ago," she says.

In the 1990s, when the HIV infection rate skyrocketed, former President Nelson Mandela ignored calls to lead a prevention campaign that could have slowed the onslaught. Millions of South African children lost their parents to AIDS during that period of neglect. Carol Diyani, who runs a care center in Soweto, says Mandela bowed to traditional sensitivities.

"It was just a taboo for him, you know, to speak openly and say men need to zip up their trousers, men need to be responsible," she says.

Soweto's largest cemetery has up to 800 funerals every month, and

they're running out of room. The majority of the fresh graves are for AIDS

victims, although few of the mourners will admit it.

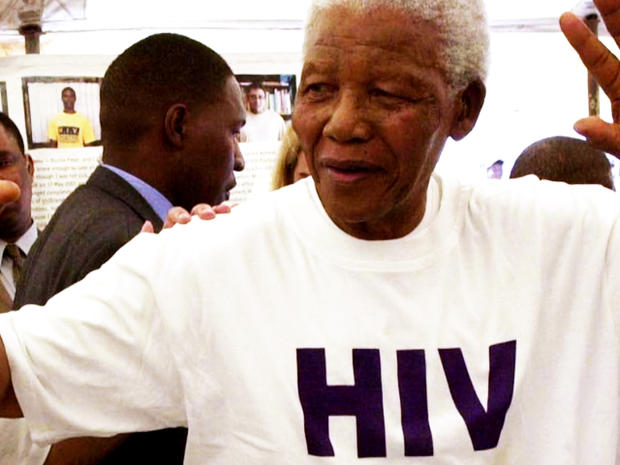

After he left politics, Mandela apologized for his failure to tackle the deadly disease.

He regretted not speaking sooner, he said, especially as he lost a son to AIDS in 2005.

"People were hiding, let me say so," Mthembu, the hospice worker, says of South Africans' attitude before Mandela acknowledged the problem. "But now, after Mandela has come, people have come out."

Even so, the legacy of neglecting HIV/AIDS for so long will ravage South Africa for years to come.