Solving the mystery of the Appalachian hiker "Mostly Harmless"

It's believed he started walking the Appalachian Trail sometime around April of 2017. From a state park in New York, he hiked south and, about a thousand miles and 10 months later, crossed into Florida.

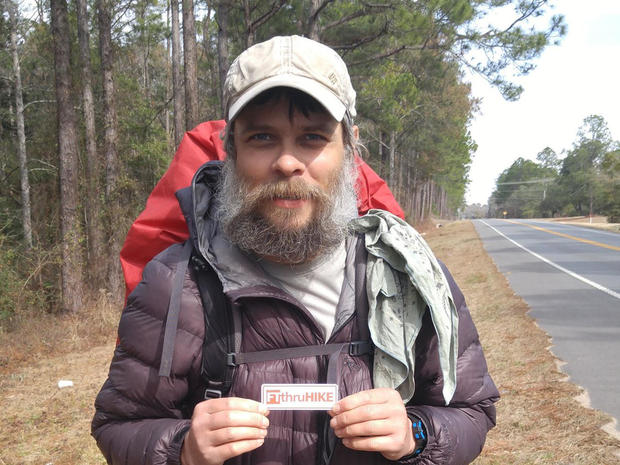

"I saw a man walking on the side of the road," said Kelly Fairbanks, a so-called "trail angel" offering help to weary hikers. "The thing that stood out to me first was his beard. Also, his trekking poles. His trekking poles let me know that he was a hiker."

Nicholas Thompson, of the Atlantic Magazine, asked, "Why did he make an impression on you?"

"He just had a really kind aura about him, and he was joking and laughing with me. Had a beautiful smile. And he had beautiful eyes – different from any other hiker."

"Sounds like you thought he was kinda handsome?"

"Yeah. Most of the women do," she laughed.

Fairbanks took a few pictures of him. So did other hikers. Some caught him on video. When asked his name, the hiker introduced himself as "Mostly Harmless." That's what he called himself when he was on the trail, and off the grid.

"He said, 'I'm not using a cell phone,'" Fairbanks recalled. "And I said, 'What do you mean, you're not using a cell phone?' And he said, 'You know, sometimes people just wanna disconnect.'"

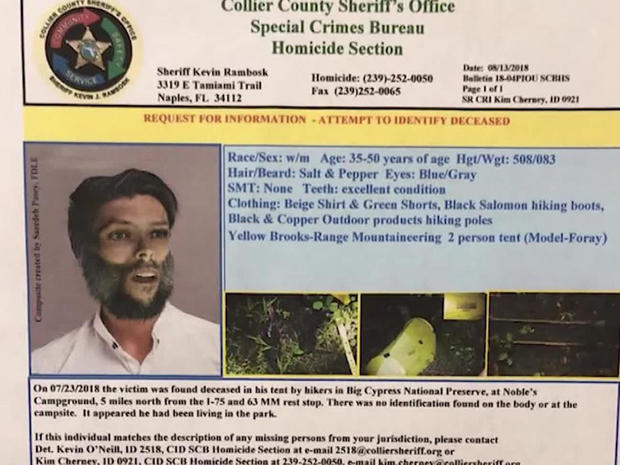

Six months after that, in southern Florida, hikers made a terrible discovery at the Big Cypress National Preserve, in Florida's Alligator Alley: A dead body had been found curled up in a yellow tent at a camp site.

David Hurm, a detective with the Collier County Sheriff's Office in Naples, Florida, said. "We had a white male, we had no electronics, no identification, no wallet, no personal information. There was nothing there that gave us a hint at the time.

"We just typically don't see people go to that length. Most people are not comfortable being completely off the grid like that."

The Sheriff's Office put out a sketch. When Kelly Fairbanks saw the picture on Facebook, she told Thompson she "freaked out a little bit."

Fairbanks was sure it was Mostly Harmless. But his real name remained a mystery. Sheriff's detectives searched databases using his face and fingerprints: nothing. The autopsy couldn't even pinpoint a cause of death.

But over the next two years the case slowly gathered attention.

"I do a lot of hiking and things like that, And that's part of the agreement – we all know that we look out for each other. You know, you don't leave someone behind," said Natasha Teasley, who manages a canoe and kayak company in North Carolina. Surfing online, she became fascinated by the case of Mostly Harmless. She helped form a Facebook group to try to identify him, named for an alias he sometimes used: Ben Bilemy. The group grew to more than 6,000 members.

"My phone stays blown up all the time with people sending me messages like, 'Could it be this person?' Or, 'Could it be that person?'" Teasley said.

She went through public records, including a government website called NamUs, a clearinghouse for missing and unidentified persons cases across the country. According to NamUs, 4,400 unidentified bodies are recovered each year.

Thompson asked, "You had to look at the face of every White man between the age of 25 and 60 who's listed as missing in the entire United States?"

"I have," Teasley replied. "And there are a lot of them. There are a lot of missing people in our country. I was not aware of how many missing people there are in our country."

That search didn't pan out. But a new high-tech tool held out hope.

David Mittelman, the founder of Othram, just outside Houston, said his lab is the only one in the United States that does advanced forensic testing in-house. Testing there would cost $5,000, money not in the Collier County Sheriff's Office budget.

Enter the online sleuths: "There was a dedicated group of folks that really wanted to see this case moved forward," Mittelman said. "And so, being that funding was the only bottleneck, when we encounter that situation, we open it up for crowdfunding. In this particular case, you know, there was so much pent-up interest in the case that we crowdfunded it, in the truest sense of the word, in about, I think, like, eight days, which was really quick."

Othram received some of Mostly Harmless' DNA from the sheriff's department and went to work. "What we do is, we capture tens of thousands of markers to hundreds of thousands of markers," said Mittelman. "And we do more of a relationship search instead of an exact match. Some people call it a genealogical search."

The results showed that Mostly Harmless was probably from Assumption Parish in Louisiana. Articles appeared online, including one that Thompson wrote for Wired Magazine which was read by 1.5 million people. Still, months went by with no positive ID.

Finally, Randall Godso, from Louisiana, saw a post.

"As soon as I saw the pictures I knew immediately – it's like, 'Oh, that's Vance!'" Godso said. "A tingle ran down my spine."

It was his college roommate.

Two-and-a-half years after his body was found, the hiker had a name: Vance Rodriguez.

The thousands of people following the case soon learned that Rodriguez was complicated. He indeed grew up in Louisiana, and he moved to New York in his 30s. He was a brilliant computer programmer whose notebooks, found in the tent where he died, were filled with computer code.

Rodriguez was estranged from his family; had troubled, even abusive, romantic relationships; and he'd sometimes disappear on his friends. Still, why had it taken so long to identify him? Partly because he had erased his tracks, and partly because no one was looking for him.

It wasn't entirely the answer that the people who'd been working on his case wanted to hear.

Thompson asked Godso, "All the people who met him on the trail describe them as friendly, amiable, easy to talk to, whereas all the other people who knew him in real life, describe him as a little distant, little bit of a loner. What's the difference? How did that happen?"

"It's not really a difference; it's a difference in when you're talking to him,'"he replied. "When he was in a good mood, he was very easy to talk to. He was very friendly. But he would also turn off and be in a bad mood, and the trail people never saw that, because if he decided he wasn't going to talk to anyone, he literally just would not talk to anyone. And so, no one would remember him [that way], I'm sure."

Natasha Teasley said, "To me, like, him being imperfect was always a possibility. We're all humans and we all have really complicated pasts. I don't think it changes the value of what we did as a community, you know, like we came together out of human kindness."

And so, Teasley started The Kindness Project. The idea is to harness the online energy that helped identify Vance Rodriguez, and to use it to identify the thousands of others who remain missing and unidentified. It's a postscript to the strange story of Mostly Harmless: an effort to give names to the nameless.

Teasley said, "My hope is that it doesn't end here, that every single person who was impacted by the story in some way will at least carry away with the knowledge of, like, care about it. Care about who these people are and that they have friends and family. They do.

"Even if you've given up that they have friends and family, they have friends and family."

For more info:

- NamUs: National Missing and Unidentified Persons System

- Othram

- Collier County Sheriff's Office, Naples, Fla.

Story produced by Alan Golds. Editor: Emanuele Secci.