Will weather cooperate for viewing the August 21 solar eclipse?

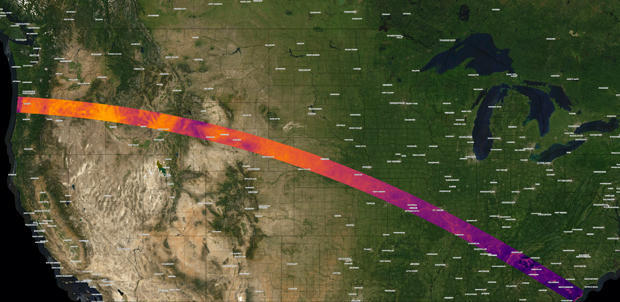

On Aug. 21, the moon's shadow will race across the United States in a 70-mile-wide corridor stretching from Oregon to South Carolina. Tens of millions hope to view the coast-to-coast solar eclipse somewhere along the narrow path of totality, while the rest of the nation will experience a partial eclipse. But actually getting to see this rare phenomenon will all come down to the weather and how much cloud cover is present at any given site.

Where will eclipse watchers have the best odds of a clear view? Historical weather data clearly favor the Northwest over the Southeast.

Jay Anderson, a retired Canadian meteorologist and veteran eclipse chaser -- this will be his 30th -- compiles historical weather data, primarily from satellites, to compute percentages for cloud cover at various sites along a given path of totality.

For the upcoming "Great American Eclipse," the data show the best chance for clear skies is near Madras, Mitchell, and Ontario, Oregon; Idaho Falls, Idaho; and then around Riverton, Wyoming, where less than 20 percent of the sky will by obscured if past trends continue.

Moving east, late August cloud cover generally increases, rising to an average of nearly 70 percent in Nashville, more than 80 percent across the Smoky Mountains and dropping back to the 70 percent range for Charleston, South Carolina.

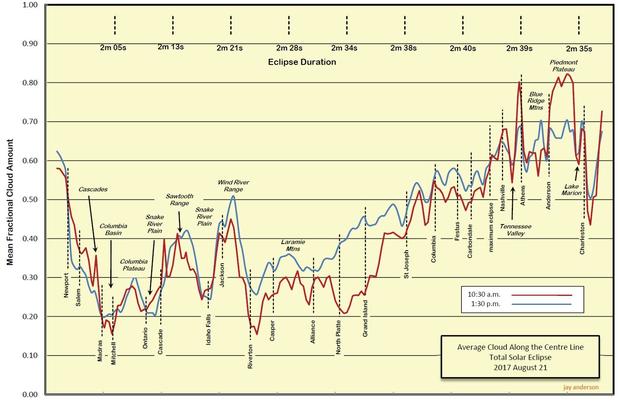

Anderson's detailed Eclipsophile website includes a state-by-stage breakdown, along with a graph (below) with a red line showing historical cloud cover at 10:30 a.m. local time at various towns and cities along the path of totality and a blue line indicating afternoon coverage three hours later.

Cloud cover, or fog, tends to be relatively high, around 60 percent, on the Oregon coast but it drops off dramatically east of the Cascades mountain range where Madras and Mitchell are located in the Columbia Basin. It climbs again crossing the Rocky Mountains and then quickly drops on the way to Riverton where it ranges from around 15 percent in the morning to a bit less than 30 percent in the afternoon.

Moving east, morning cloud cover is typically 30 percent or less between Riverton and Grand Island, Nebraska, with afternoon buildups climbing to more than 40 percent. The two lines generally converge around 45 percent near St. Joseph, Missouri, and climb steadily as one moves east.

"There are two things that come out with that graph," Anderson, 70, said in an interview. "First of all, it follows the topography. The mountains are cloudy and the valleys are sunny. The second thing is that the difference between morning and afternoon is about what I'd expect."

The western U.S. will get morning viewing, with the total eclipse first appearing over Oregon's Pacific coast at about 10:16 a.m. local time (1:16 p.m. EDT). It will exit over South Carolina about an hour and a half later, at 2:48 p.m. EDT.

Across the Great Plains, Anderson said, the morning sky is relatively sunny with cloud cover building up in the afternoon. But as one moves east of the Missouri River, "there's not very much difference between morning and afternoon, and that's because it's a much more humid environment."

"Once you get east of Missouri, you get the moisture on the west side of the Appalachians coming up from the Gulf of Mexico and you've got it on the east side of the Appalachians coming from the subtropical Atlantic," he said.

The clear message from the historical data is that eclipse watchers will have a much better chance of clear to mostly clear skies in the western portions of the path of totality. Even so, Anderson cautioned that historical data is just that, and conditions at any given site could be better or worse than expected.

"I've done a fairly extensive survey of the people that go to eclipses and you miss about one in eight," he said, due to bad weather. "There are some people who say 'I've been to 15 of them I haven't missed one yet.' But then there are people who have been to four and haven't seen it yet.

"But I did a survey of all the people on the solar eclipse news list, because there are some published statistics there, and one in eight is about the number of eclipses you miss. That's pretty darn good average, and I think it's a reflection of the fact that we have all of this global weather (data) nowadays."

Ryan Keisler, a machine learning expert at Descartes Labs, which uses satellite data to track natural and human influences on a global scale, ran his own review of historical weather data, producing a color-coded chart indicating the likelihood of clouds along the path of totality. His plot also favors the Northwest.

But like Anderson, Keisler said historical data only goes so far. As the eclipse gets closer, realtime forecasts should drive one's decisions about where to view the eclipse.

"If you're trying to plan out two weeks from now, or three weeks from now, this is a good chart," he said. "If it's three days before the event and you're trying to plan, then you should use your real-time weather forecast, not this. That'll give you a much better picture of what's going to happen on the day of (the eclipse)."

Anderson recommends two weather websites that present a variety of forecast models and maps.

SpotWx will generate forecasts for virtually any location using a variety of numerical models, generating graphs of cloud cover, precipitation, temperature, wind speed, humidity, etc.

The College of DuPage's Next Generation Weather Lab provides an extensive set of weather analysis tools, including up-to-date satellite imagery, radar and numerical models that can be applied to any location along the path of totality or elsewhere.

Anderson matches historical data with personal experience. In 2013, he and a friend drove the entire eclipse track, from coast to coast, "and talked to people along the way. ... It was kind of fun to do that, and just sort of share a little astronomy with people. It was a great trip across America."

He's noticed a change from years past, when scare stories about the risk of eclipse-related eye injuries dissuaded some viewers.

"And the main part of that is because it's become monetized," he said. "All these communities have a financial stake in the successful watching of this eclipse, and anybody who sticks their head up and says 'stay indoors, watch it on television,' everybody comes back and says look, we got all these eclipse glasses, we know how to do it safely, we're gathering together in the stadium, we're going to have experts telling us when we can look and can't look."

During a more localized eclipse in 1979, "naysayers jumped on it and a lot of people stayed indoors actually frightened about it," Anderson said. "This one's going to have everybody out looking at it."