Will a calmer sun create a cooler planet?

To understand the power of the sun, it helps to study the sunspots that wax and wane every year.

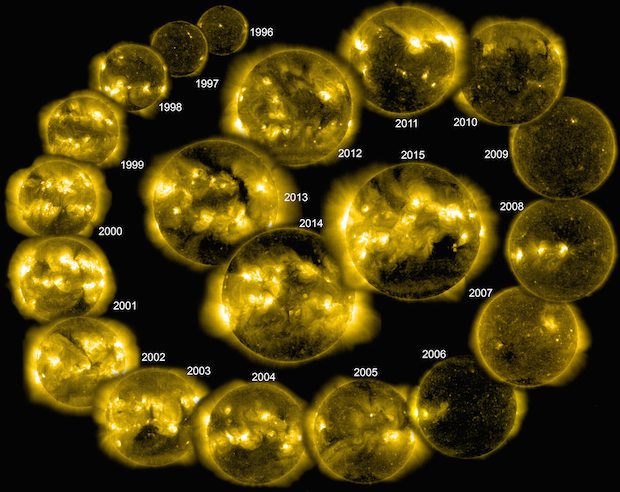

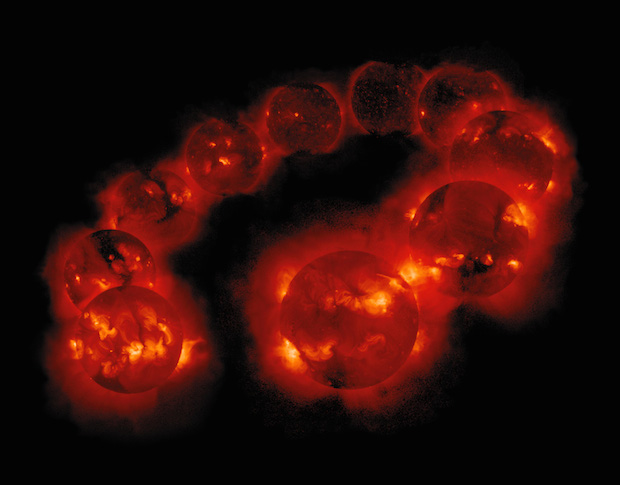

Brighter images in this composition show times when there was more activity or less on the sun - known as solar minimum and solar maximum. This activity is driven by the sun's magnetic field and follows a cycle of about 11 years. When there is a solar maximum, the magnetic field of the sun is highly dynamic, changing its configuration and releasing energy, partly in the form of ultraviolet radiation into space.

Among the changes that have struck scientists in recent decades has been a relative decline in activity - with sunspot activity lower than it had been in a century.

Some chalked it up to natural variation while others warned something more was happening - with historic lows in solar wind pressure and solar irradiance. NASA even addressed the question of whether sunspots were gone forever after, in 2009, the sun encountered its deepest solar minimum in nearly a century.

But just when scientists feared it was getting too quiet, activity has picked up in recent years. That said, the solar cycle has become a political football of sorts in the climate change debate.

Climate skeptics early on used intense sunspot activity in the 20th century to explain a rise in global temperatures - much to the chagrin of mainstream scientists. Now, there is a chance they may seize on the new research that projects that sun spot activity could cease in 15 years - an event known as a grand solar minimum - which could prompt a significant temperature drop.

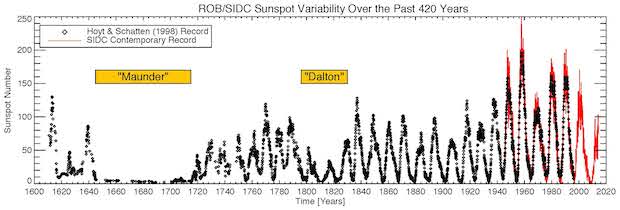

If it happened, it wouldn't be the first time. In the 17th century, the sun plunged into a 70-year period of spotlessness known as the Maunder Minimum.

It coincided with what is called the Little Ice Age, when temperatures dropped and Europe and North America experienced brutally cold winters. But scientists say the cold spell cannot be attributed solely to a decline in solar activity, since there was also an uptick in volcanic activity at the time.

Using a new technique to measure the sun's magnetic waves, Valentina Zharkova, a professor of mathematics at Northumbria University in England, told the Royal Astronomical Society's National Astronomy Meeting last week that sunspot activity could drop as much as 60 percent to 70 percent between 2030 and 2040 from the current cycle.

She is predicting temperatures will also decline several degrees as they did in the 17th century but is open to the possibility that global warming could offset some of those decreases.

"It will really be a decrease in the temperatures but how it will be propagated to Earth, only the atmospheric people will tell you. I didn't do this research," Zharkova, who co-authored a paper with some of the findings last year in The Astrophysical Journal, told CBS News. "Either way, it looks like the sun gives us the second chance to sort out human-induced emissions while it is in the minimum of activity before any worse case scenarios can come (into) play."

But her conclusions have been met with skepticism from other solar scientists and those who study the climate. Most climate experts are suggesting any changes in the solar activity will have little impact on the Earth's climate.

A 2011 paper Geophysical Research Letters suggested a drop in solar activity would mean only a 0.5 degree drop in temperature while a paper out in June in Nature Communications found such a decline from 2050 to 2099 "is likely to be a small fraction of projected anthropogenic warming," delaying the effects of climate change by only two years.

Still, the paper by Sarah Ineson, of the Met Office Hadley Center, and her colleagues predicted a drop in solar activity could disrupt regional climate. They predicted that among other things "enhanced relative cooling over northern Eurasia and the eastern United States," would help to offset some of the warming.

But most researchers acknowledge predicting just what the sun does is next to impossible because it is such a complex system that is still largely a mystery - including how it produces sunspots and how it goes into and out of these grand solar minimum states.

To make that point, Scott McIntosh, director of High Altitude Observatory of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, pointed out the sun not only has 11-year spot cycle along but also a 22-year magnetic cycle and 100-year cycles "that we have no idea about."

"We don't really have a name for them," he said of the longer cycles. "They could be responsible for these periods where sun spots just switch off. One of the problems with those, even when the sunspots switch off, the sun's magnetic field doesn't. So it's really a complicated puzzle."

McIntosh said solar activity is down about 33 percent from where it was 25 years ago but that scientists haven't been able to pinpoint how it is shaping our climate.

"Even though the sun's variability is going down markedly, we don't really understand the real connection between the change in magnetism and the amount of the light the sun puts out," he said. "That is the thing that drives climate."

And predicting the future of the sun's activity and its impact on Earth's temperatures? Forget about it.

"I think it's an incredibly difficult thing to predict," McIntosh said.

"Most of our work is hind-casting. We have to wait until it's done," he said. "To tell a solar maxim has happened, we have to wait some period after it's happened to proclaim that was a solar maximum. To project out 30 years, take that for what it is. It is incredibly difficult to do for a system we are only beginning to scratch the surface of."