Former soccer star Bruce Murray speaks out on his struggles with memory, possible link to CTE

When we think of the risk of concussions in athletes, sports like football and hockey often come to mind. But researchers have also been focusing on a different sport: soccer.

Bruce Murray, a former soccer star who retired in 1995 after multiple concussions and collisions, is speaking out about his own struggles with memory and why his days on the field may have caused chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Concussions have already been linked to CTE, but now researchers believe smaller repetitive hits to the head may also be responsible.

The stealth disease has no cure and can only be diagnosed after death. Symptoms of CTE include trouble with memory, problems organizing and planning simple activities, and changes in behavior, such as lack of motivation or having a short temper.

Murray, who was at the top of his game in 1990, kept a reputation for being a fearless player at Clemson University before playing forward for Team U.S.A. But his aggressive play sometimes left him seeing stars, including during a match in Saudi Arabia, where a Saudi player's knee caught him in the head.

"I was on my hands and knees, trying to find where my equilibrium was, but for the next six weeks to a month, I would go places and not know why I was there," he told CBS News' chief medical correspondent Dr. Jon LaPook.

Murray decided to finally hang up his sneakers at age 29 as he continued to experience post-concussion symptoms like lack of sleep, headaches and light-headedness.

"My body just felt beaten up," he said.

When CBS News visited Murray and his family in Maryland two years ago, he was troubled by recent lapses in memory, including one that left him especially shaken. He was in a car waiting for his wife and son to return from a store when they came out and he didn't immediately recognize his own wife, Lynn.

Because of Murray's history of concussions, the couple reached out to Boston University's center for chronic traumatic encephalopathy, also known as the CTE Center. Since CTE can only be diagnosed after death, researchers scanned Murray's head for clues, and they found one: his brain tissue had atrophied, or shrunk.

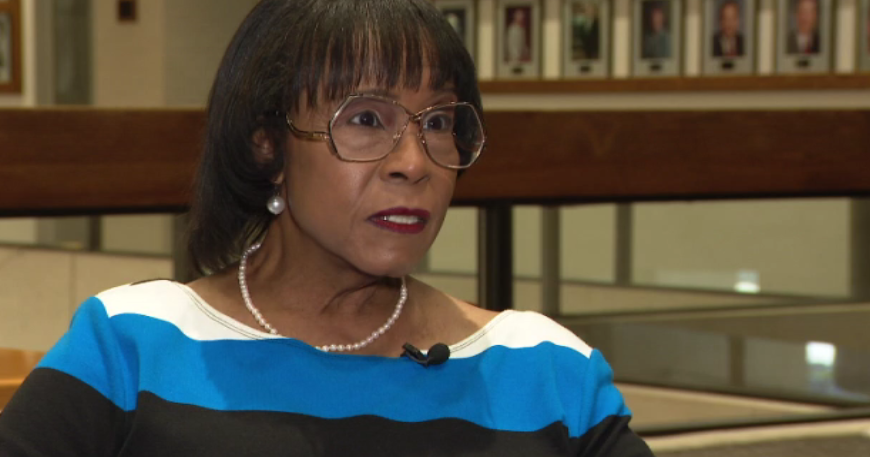

Dr. Ann McKee, director of the CTE Center, has examined the brains of hundreds of deceased veterans and athletes, including football player Aaron Hernandez, who died by suicide while serving a life sentence for murder. She said concussions are not the only cause of CTE, and warns that damage from asymptomatic hits may accumulate over time and lead to a higher risk for CTE.

McKee says the risk of head trauma from heading a soccer ball is concerning and that "there's an argument for taking heading out of soccer." An estimated 13 million children play soccer in the United States, and McKee believes more needs to be done to protect athletes of all ages.

"Those balls are coming from a great distance at a tremendous velocity, and that impacts the head and leads to these injuries later on," she said.

U.S. Soccer, which governs the sport from kindergarten through the elite level, has extensive concussion protocols, and it bans or limits headers in children 13 and younger. But when it comes to sub-concussive hits in older players, U.S. Soccer told CBS News it is awaiting more research. The organization declined our request for an on-camera interview.

Murray said his condition appears to be stable, but he continues to struggle with memory, focus and balance. He still enjoys coaching youth soccer, but believes the sport he loves may need changes to make it safer for everyone.

"I think U.S. Soccer needs to address this," Murray said. "It's called football all around the world. What if you rewrote the rules? Do you have to head the ball?"