Skin cancer-detecting smartphone apps may not be accurate

Smartphone apps that claim to be able to tell if a person's skin lesions are cancer may not be as accurate as advertised, according to a new study.

"It seems so appealing," lead researcher Dr. Laura Ferris, assistant professor at the Department of Dermatology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, told NPR. "Unfortunately, our data suggest that maybe these apps aren't quite there."

The research, which was published in JAMA Dermatology on Jan. 16, showed that only one out of four popular smartphone apps that purported to evaluate a person's risk for skin cancer was found to be statistically accurate. However, that particular app costs $5 per submission and took 24 hours to deliver a result, whereas the other inaccurate ones were free or had a low cost.

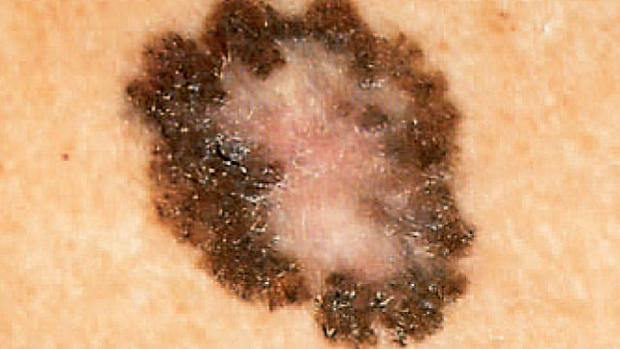

Skin cancer is the most common form of cancer in the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports, with basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas the two most common types of the disease. Both of those are highly curable, however the third-most common type, melanomas can be more dangerous. In 2009, 61,646 people in the United States were diagnosed with melanomas, and 9,199 people died that year from the disease.

- Scientists: Genes, not sun, behind redheads' increased melanoma risk

- Melanoma on rise in young women: Why?

- Skin cancer risk reduced by taking aspirin, ibuprofen, study shows

Researchers uploaded 188 images of skin lesions to four different apps that were found on the two most popular smartphone platforms. The apps either reviewed the images using an algorithm or pictures were reviewed by an anonymous board-certified dermatologist. All apps contained disclaimers saying the information provided was for educational purposes only, and people shouldn't rely on them above seeking professional medical advice.

The app that relied on the board-certified dermatologists only missed one of the 53 melanomas included in the image submissions. The other three apps incorrectly diagnosed 30 percent or more melanomas as "unconcerning," and identified many benign growths as potentially cancerous. Overall for all four apps, the likelihood that the disease was melanoma when a picture of melanoma was presented was only correctly determined in 33 to 42 percent of the cases.

Ferris told NPR that apps that monitor the changes in moles over time and send self-exam reminders may be more helpful than self-diagnosing apps. These apps store photos of the moles so a concerned individual can bring them to the doctor.

But, researchers fear that many low-income people may rely on the free apps to save them medical costs, and might be falsely comforted by the information the app gives them.

"If they see a concerning lesion but the smartphone app incorrectly judges it to be benign, they may not follow up with a physician," Ferris said in a press release. "Technologies that decrease the mortality rate by improving self- and early-detection of melanomas would be a welcome addition to dermatology. But we have to make sure patients aren't being harmed by tools that deliver inaccurate results."