Creating a virtual choir with 17,572 singers

The coronavirus hasn't been kind to choirs. Think about it: You're packed in together, breathing deeply, mouths open wide. It's a recipe for super spreading.

Choirs can't sing together over video chat, either; the Internet introduces about a half-second delay, making it impossible to sync up.

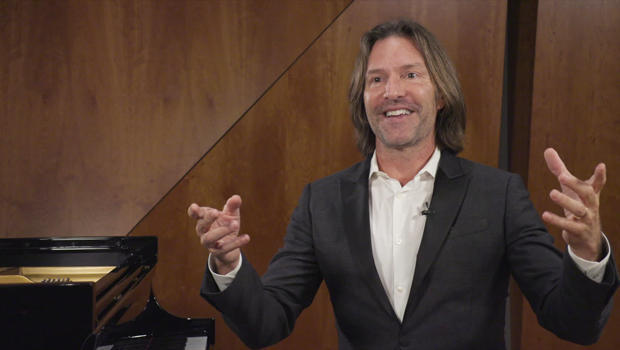

But in 2009, way before the pandemic, Grammy-winning composer Eric Whitacre figured out how to build a choir without having the singers in one place: "This idea came up which was pretty simple: I would upload a video of myself conducting the piece. And then people sat alone in their rooms and followed my conductor's track, and sang along to it. If I uploaded all of those videos and I started them at the same time, this choir would have to emerge, a virtual choir."

One-hundred-and-eighty-five singers participated in that very first virtual choir:

"Lux Aurumque" performed by Eric Whitacre's Virtual Choir (2010)

"I got that final video back and I immediately realized, 'Oh, this is so much bigger than I'd imagined,'" Whitacre said.

That video went viral. In the years since, Whitacre and his team have created more virtual choirs, each one bigger than the last: 2,000 singers in "Sleep" (2011); 3,700 singers for "Water Night" (2012); 8,000 singers for "Deep Field" (2018).

But they were just barbershop quartets compared to Whitacre's newest piece: "Sing Gently," featuring 17,572 singers from 129 countries. It's the biggest virtual choir ever assembled.

"It was only when the COVID crisis started that we thought, 'Actually, if there was ever a time for one of these virtual choirs, it would be now,'" Whitacre said.

In March, with all his performing and speaking engagements canceled, he began writing the music. "I was inspired by what I was seeing around me: people in isolation. And I wrote the music and words to this very delicate, simple piece called 'Sing Gently.'"

He recorded an accompaniment video to guide the singers, and set a deadline for singers to turn in their recordings.

"Sunday Morning" contributor David Pogue was one of them.

Singing all by yourself on camera, with no other voices to smooth the rough edges, you feel like an idiot, he said: "I hope Eric doesn't listen to mine by itself!"

"We all felt that!" said Ashley Ballou-Bonnema, a fellow virtual choir participant.

As Pogue got to know some of the other singers, he realized how inclusive a virtual choir can be. You can live anywhere in the world. Maybe you're five years old, or 87. Maybe you're blind. Maybe you're deaf.

Alexandria Bailes signed the lyrics instead of singing. "I did this as a personal reflection from how I was feeling at the time with everything that was going on in the world," Bailes said through an interpreter. "Feeling that sense of isolation. I wanted to express that in my language, which is American Sign Language."

You might not expect Ballou-Bonnema to be in choirs at all. She has cystic fibrosis; catching even a cold could be devastating to her health. "It can be pretty lonely, though, in that sense of extreme isolation, and I think that's where the virtual choir really comes into play," she told Pogue. "'Sing Gently" was the means in which we could still feel like we are contributing to something and creating something in the midst of all this destruction and uncertainty."

Pogue asked Whitacre, "With each virtual choir you've done, the number of participants keeps going up and up and up. Are you secretly thrilled inside? 'This time 17,000, next time, the world'?"

"It's the exact opposite," Whitacre replied. "The irony is that for every virtual choir, we pray that the numbers will be low. Because on the back end, it is so much work. You need to listen to every single video."

Yes, they watch every single video submission. That way they can weed out the ones with technical problems, like intrusive cats and ringing mobile phones.

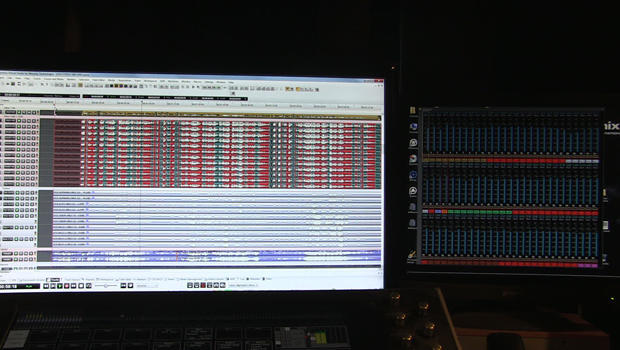

Every usable recording winds up in the finished piece. With only six weeks until the premiere, the engineers work on the audio first, mixing together the recordings of two hundred singers at a time.

Meanwhile, a graphic specialist creates the computer animation that incorporates all those videos.

The finished song premieres today on YouTube, at 1:30 p.m. ET. It's about three minutes long, plus seven minutes of credits.

Pogue asked, "Is there a downside of making choirs this way?"

"The downsides of virtual choirs are legion," Whitacre said. "A virtual choir is this gorgeous, delicate, ephemeral artwork. And what's beautiful about it is that it will exist for all time. But singing together in a room, taking that first breath together, and then singing together, I mean, nothing beats that, and nothing ever will."

WATCH AN ARCHIVE RECORDING OF THE FACEBOOK LIVE CHAT (featuring David Pogue and composer Eric Whitacre):

For more info:

Story produced by David Rothman.