Federal jobs aren't the ticket to a middle-class life they used to be

In Washington, D.C., so many furloughed federal workers have sold clothing to make a few bucks that one thrift store was overwhelmed by donations. An office manager for the Environmental Protection Agency started working nights in a local restaurant. And a dozen air traffic controllers resigned this week over being forced to work without pay during the partial government shutdown.

Working for the U.S. government—once seen as a ticket to a stable middle-class life—now looks like a road to professional and financial insecurity. This is the 21st government shutdown since Congress adopted new budgeting procedures in 1976, according to the Congressional Research Service, and it was the third in 2018 alone.

"For some folks, the volatility of being in this type of position is jarring. The federal government has always been seen as a stable employer, and suddenly, they don't pay you?" said Alan Moore, one of the founders of the XY Planning Network, a group of fee-only financial advisers.

The group last week offered free financial planning services to government workers affected by the shutdown. Along with helping furloughed workers consider their financial options, such as taking out a personal loan, advisers also are "starting to have some career conversations," he said.

That shift is a stark one for the kind of work once coveted for offering job security, decent pay and the satisfaction of public service. In return for a steady schedule, lower turnover and a decent retirement, many federal workers willingly accepted lower pay than what they might've earned in the private sector.

"For many government workers, it's still a chance to have real upward mobility but also be able to balance work and life," said David Van Slyke, dean of the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University. "It's 40-45 hours a week of work, but you still can have upward mobility, positive benefits and have purpose in your job."

For many workers, the federal workplace can offer more predictable promotions and better career development, Van Slyke added, noting that the government doesn't have to show investors that it's profitable and growing every quarter. "For better or for worse, there's not the same short-term profit motive," he said.

Early de-segregation

Government work has been especially important for black Americans, who historically were shut out of many private-sector jobs. The federal government was one of the first sectors of the economy to de-segregate in the 1960s; state and local governments soon followed, allowing many African-Americans to enter the middle class. Even today, black and Latino workers are better-represented in public-sector jobs than in the broader U.S. workforce.

Government work has been particularly important for workers with less education or lower skills. For example, the lowest-paid postal employee in Des Moines, Iowa, earns $15 per hour, federal data show -- more than twice the U.S. minimum wage of $7.25 an hour. (For more senior positions, federal workers' salaries typically top out at much lower levels than what they could command in the private sector.)

In recent years, however, federal workers have lagged their private-sector counterparts when it comes to getting a pay hike. Federal workers' pay, which is set by Congress, rose only 1.7 percent in 2018, while this year President Donald Trump canceled federal raises outright.

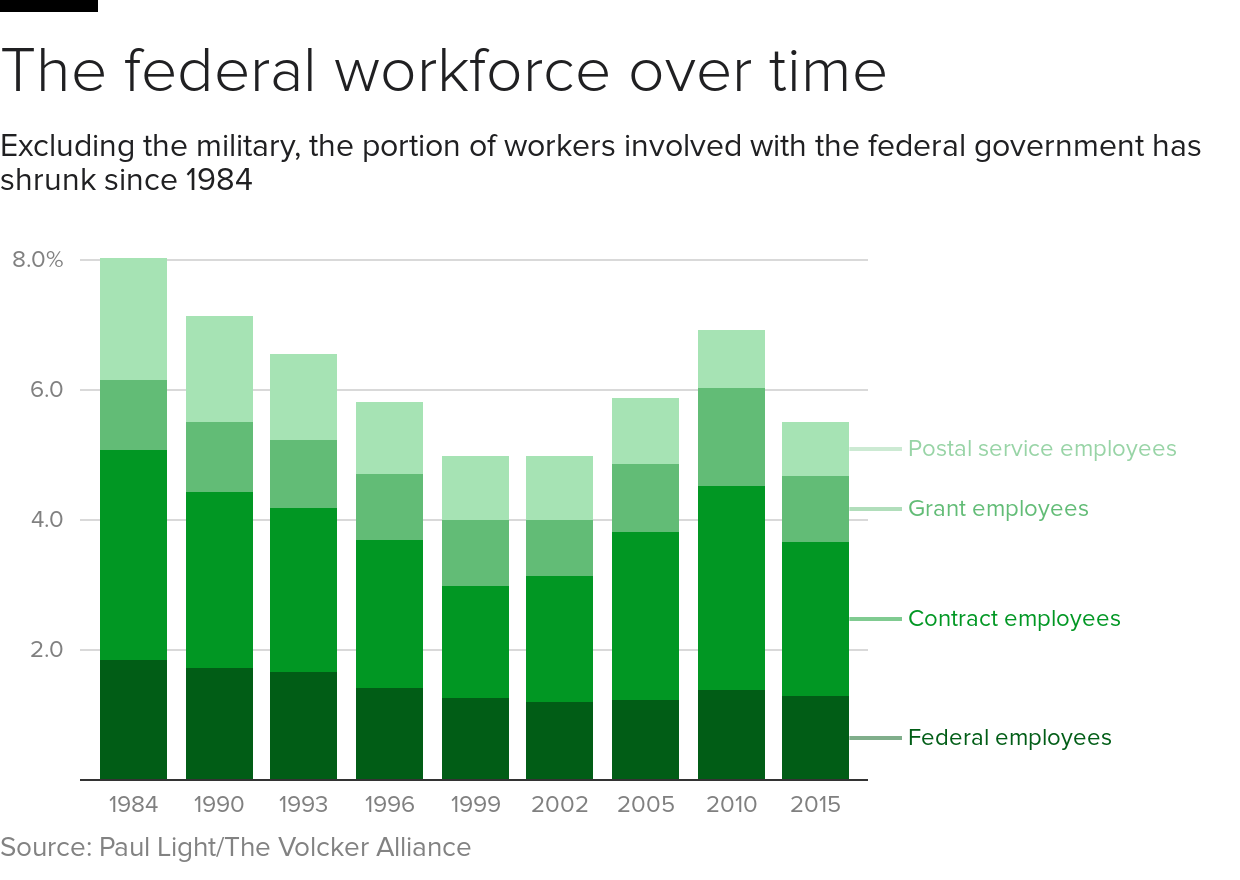

The number of people working for the federal government today is the same as it was 35 years ago, even while the overall workforce has added 4 million people. A much larger share are contractors who work for a private company that does government business. Besides being more vulnerable to shutdowns than employees, contractors are also more likely to be poor than federal employees and the broader workforce, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

"I've tried to be prepared"

Some government workers have faced criticism after going public with stories of financial hardship.

"I've had people tell me I should take Dave Ramsey's financial course so I'm better prepared," said Sarah Watterson, a former U.S. Marine and married mother of two who's been on furlough from her EPA job since late December.

"I've tried to be prepared, but how do you budget when you don't know what the end is?"

Most Americans lack the savings to cover a surprise $1,000 emergency expense, according to Bankrate. In that respect, federal workers are no different: According to one estimate, a worker sidelined in the shutdown has now missed out on $7,000 in pay on average, Sentier Research found. The typical worker furloughed in this shutdown earns a median of $67,000 a year, according to Sentier. Half of the workers affected are the only earners in their household.

Watterson doesn't know when she'll get back to work. But she said she was feeling "a little bit better" since starting a night job in a local restaurant last week. She's working in the kitchen and will be doing deliveries, Watterson said.

She made sure to only look for jobs on evenings and weekends, because once she's back at the EPA, she plans to keep the second gig, she said. "I would like to get ahead and have a lot more in savings because this does come up, and it's very stressful."