America's sex ed controversy: Can you teach consent?

Watch the new CBSN Originals documentary "Sex. Consent. Education." in the video player above.

When Amy Fortier-Brown took a sex education class in high school, she learned how to avoid getting pregnant and how to protect herself from STDs. Before that, she learned abstinence in her middle school health classes. She doesn't remember learning anything about consent, sexual assault or what to do if it happened to you until college.

But by then, she says, it was too late. She'd been assaulted by someone she was dating in high school.

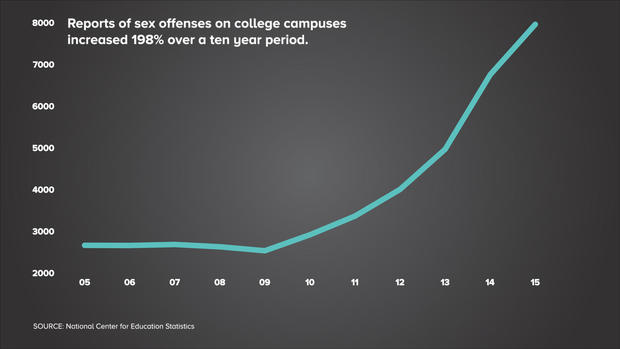

In recent years, the issue of consent — what it means, and how it is given — has become a cultural topic of conversation. Significant increases in the number of reported sexual assaults on college campuses and the #MeToo movement have left many wondering, how can we prevent these situations from happening in the first place?

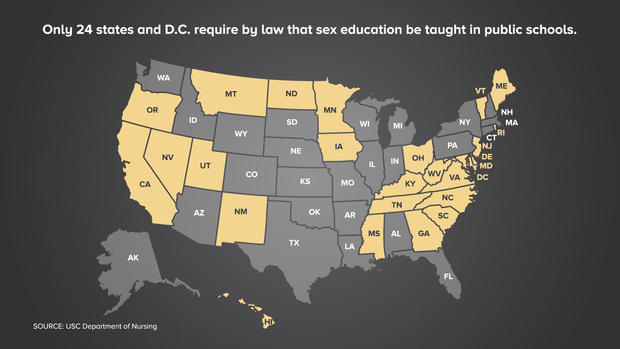

Some believe a different approach to sex education could help. There is no federal regulation mandating sex ed or what should be taught. Each state is left to decide on its own guidelines and what the curriculum should be. Individual school districts then choose how to implement that curriculum.

Only 24 states and Washington, D.C. have laws on the books mandating sex ed be taught in public schools. Communities in the rest of the country have varying degrees of regulations. In some districts sex ed isn't taught at all, and when it is, the content of what is taught can vary widely. Some students might be instructed on abstinence until marriage, where others might learn about STDs and condoms. Many get a mixture of both.

Either way, incorporating an understanding of consent into those lessons hasn't always been the norm. States across the country are now considering changing that. Maryland and Colorado, for example, recently passed laws requiring a more comprehensive approach that includes conversations about consent and sexual assault.

"Because it's not talked about, kids don't know what exactly consent is," said Alicia Gill, an educator with a non-profit clinic called Life Choices in Dyersberg, Tennessee. Her main goal is to promote abstinence as the best choice, but she educates students about sexually transmitted diseases, birth control, and dating violence prevention as well.

In her lessons, she teaches that consent must be enthusiastic and freely given — and that it can be revoked. "We really, really like to drill that into them so they know it's OK to change your mind. It's OK to say yes, then in the heat of the moment, change your mind."

Colleges and universities are also looking for ways to decrease the number of assaults happening when young adults go away to school. From 2005 to 2015, the number of reported sexual offenses increased 198 percent, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

"About 50 percent of all of the assaults on campus are going to happen in the person's first month of their first semester of college," said Fortier-Brown, who is now a senior at the University of Maine, Farmington. "We can stop that, or we can at least mitigate that by, A) educating people on what consent is, but B) educating people on how to protect themselves. Because unfortunately that's a part of it."

One popular trend is for schools to present a skit or seminar about consent during freshman orientation. Some schools require students to take an online tutorial. Experts, however, say that's not enough.

"I think where we haven't figured out yet, on college campuses, how to do this education. Everyone is all over the map," Donna Freitas, author of "Consent on Campus: A Manifesto," told CBS News. "We need to create ongoing spaces. There's not even a human sexuality course you can take at most universities."

Fortier-Brown is trying to address that problem at her school. After a sexual assault scandal rocked their campus, she and other activists took a number of proposals to the school administration, including a request for a health class that would address the gap in sex education.

But she and many experts in the field believe this education needs to start well before college, to create a foundation of knowledge long before young people have to navigate their first romantic relationship or sexual experience.

"In kindergarten, you would talk about concepts," said Chitra Panjabi, the former president and CEO of the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States.

"Consent looks like being able to say, if you don't want to be touched, you can tell someone, 'I don't want to be touched.' Or that you have to respect someone when they say that to you. You know, by the time you look at 8th grade or even 12th grade, what those concepts mean will be fleshed out out within the context of sexual health and sexuality education more broadly, that's age and developmentally appropriate."