9/11 museum called reminder "that freedom is not free"

NEW YORK -- Leaders of the soon-to-open Sept. 11 museum portrayed it as a monument to unity and resilience ahead of its dedication Thursday, saying that the struggles to build it and conflicts over its content would be trumped by its tribute to both loss and survival.

"It tells how in the aftermath of the attacks, our city, our nation and people across the world came together," former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the memorial foundation's chairman, said at a news conference Wednesday. "This museum, more than any history book, will keep that spirit of unity alive."

After Thursday's dedication, then six days of being open around-the-clock to Sept. 11 survivors, victims' relatives, first responders and lower Manhattan residents, the National September 11 Memorial & Museum opens to the public May 21. It is a testament to how the terrorist attacks that day shaped history, from its heart-wrenching artifacts to the underground space that houses them amid the remnants of the fallen twin towers' foundations.

As museum leaders see it, it is both a site of remembrance and a palpably physical forum for examining the post-Sept. 11 world. To museum Director Alice Greenwald, "it is about understanding our shared humanity"; to Bloomberg, a reminder "that freedom is not free."

In an interview with CBS' "60 Minutes" that was broadcast last September, Greenwald spoke about the difficulties encountered in creating the museum.

"When you come down to questions like, you know, do you include the recorded audio of a person in a burning building on the phone with a 911 operator, how far do you go in making your point?" Greenwald asked. "How much of the authentic material are you obligated to share and when does it become inappropriate? And that debate - there's no one answer."

The memorial also reflects the complexity of crafting a public understanding of the terrorist attacks and reconceiving ground zero.

Over the years, the museum faced financing squabbles and construction challenges. The museum and the memorial plaza above it cost a total of $700 million to build and will cost $60 million a year to run, more than Arlington National Cemetery and more than 15 times as much as the museum that memorializes the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Sept. 11 museum organizers have noted that security alone costs about $10 million a year.

Conflicts over the museum's content underlined the need to memorialize the dead while also honoring survivors and rescuers, of balancing the intimate with the international.

Holocaust and war memorials have confronted some of the same questions. But the 9/11 museum exemplifies the work it takes to "develop a museum program amidst this range of powerful feelings and differing individuals and issues that get raised," said Bruce Altshuler, the director of New York University's museum studies program. He isn't involved in the Sept. 11 museum.

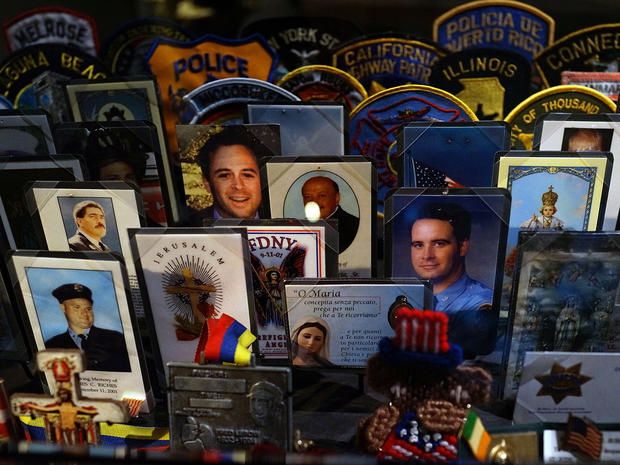

The museum harbors both personal possessions and artifacts that became public symbols of survival and loss. There is the battered "survivors' staircase" that hundreds used to escape the burning skyscrapers, the memento-covered last column removed during the ground zero cleanup and the cross-shaped steel beams that became an emblem of remembrance. (An atheists' group has sued, so far unsuccessfully, seeking to stop the display of the cross).

Portraits and profiles describe the nearly 3,000 people killed by the Sept. 11 attacks and the 1993 trade center bombing. Almost 2,000 oral histories give voice to the memories of survivors, first responders, victims' relatives and others. In one, a mother remembers a birthday dinner at the trade center's Windows on the World restaurant the night before her daughter died at work at the towers.

The museum also looks at the lead-up to Sept. 11 and its legacy - and that has sparked some of the controversy it has faced.

Members of the museum's interfaith clergy advisory panel raised concerns that it plans to show a documentary film, about al Qaeda, that they said unfairly links Islam and terrorism. The museum has said the documentary is objective; Bloomberg said it took care "to make sure that nobody thinks a billion people who practice one religion were responsible."

While not speaking about the film, historian Ed Linenthal, a professor of history at Indiana University who has written books about the Oklahoma City and U.S. Holocaust museums, said during a "60 Minutes" interview broadcast in September that it's a difficult question over including the perpetrators at a memorial museum.

"How could these memorials to these searing events not in themselves be searing?" asked Linenthal. "I mean, there would be really something wrong if we could say, 'Oh, sure, memorial to 9/11? Yeah, we'll knock that out in a month or so.'"

While some Sept. 11 victims' relatives have embraced the museum, others have denounced its $24 general-public ticket price as unseemly and its underground location as disrespectful, particularly because unidentified remains are being stored in a private repository there. Other victims' families see it as a fitting resting place.

Charles G. Wolf, who lost his wife, Katherine, said he felt the tug of mixed emotions as he anticipated seeing the museum Thursday.

"I'm looking forward to tomorrow, and I'm dreading tomorrow," he said Wednesday. "It brings everything up."