In clinical trials and laboratories, the hunt is on to find vaccines and drugs to treat, prevent novel coronavirus

With the novel coronavirus extending its shadow of illness and death globally, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health are now slashing red tape to expedite research so promising vaccines and therapies can be developed as quickly as possible. To date there is no proven medical way to stop this coronavirus - no treatment, no vaccine. The best defense has been tried-and-true public health measures: social distancing and hand washing. But the rapid spread of the deadly virus prompted medical researchers the world over to go on offense. Old medicines are being dusted off and repurposed, new vaccines are being developed in government and commercial labs. We went to Omaha, Nebraska, where one of those drugs is being tested on some of the sickest American patients.

At the University of Nebraska Medical Center, one of the eerier scenes we've witnessed in recent weeks. Cocooned inside that bubble, called an isopod - a 36-year-old woman - unlucky to have been infected with the new coronavirus, but lucky to be here. This facility was one of the first in the country built for outbreaks like this. Some of the sickest patients from the Diamond Princess cruise ship were taken there. Quarantined in Yokohama, Japan, more than 700 passengers and crew contracted the virus, including 67-year-old American Carl Goldman. He was quarantined here for a month. We had to talk to him through thick glass.

Carl Goldman: When we landed in Omaha, more officials came onboard with hazmat suits. They unloaded me, put me on a stretcher. They were wheeling me through passageways that were deserted then up an elevator, and then into a room that was set up as a bio-containment room.

Bill Whitaker: They moved you to a bio-containment room?

Carl Goldman: Yeah.

Dr. Angela Hewlett is the medical director of the bio-containment unit, equipped to care for patients with highly contagious, dangerous diseases. Built in response to the 2001 anthrax scare, the unit is isolated from the rest of the medical center, with its own ventilation system, security access and highly trained staff: about 100 nurses, therapists, critical care and infectious disease doctors.

Bill Whitaker: How many patients can you treat at one time?

Dr. Angela Hewlett: We could actually accept up to probably eight patients in the biocontainment unit, totally dependent on how sick they are and how much equipment is required.

Bill Whitaker: How many facilities like this are there around the country?

Dr. Angela Hewlett: We have 10 regional treatment centers with those capabilities.

Bill Whitaker: Given the scope of this outbreak, that doesn't seem nearly enough. And when I see the Isopods being used to bring people into this facility, that makes me think that this is pretty bad.

Dr. Angela Hewlett: If we had a-- a therapeutic agent that we knew worked or if we had a vaccine that could help prevent the spread of this illness, then-- you know, then this would be something a little more controllable than what we have now.

Researchers at the University of Nebraska Medical Center modeled a worst case scenario in the U.S.: over the course of a year, 96 million cases of COVID-19; 4.8 million hospitalizations; almost a half-million deaths. Scientists hope the measures the country is taking will keep the worst from happening, but the urgency of this moment has medical researchers all over the world racing to find some way to fight the killer virus. Last month, the National Institutes of Health tapped the Nebraska Medical Center to launch the first clinical trial in the U.S. of an antiviral drug, remdesivir, which is administered intravenously to treat patients who have already contracted the virus. It's being tested against a placebo.

Dr. Angela Hewlett: It was actually studied in Ebola, interestingly. Didn't work as well for Ebola. However-- there have been some animal studies as-- as well as some studies in the lab that demonstrate that it worked fairly well against illnesses like SARS and MERS, which are also coronaviruses.

Bill Whitaker: How does the drug work?

Dr. Angela Hewlett: It inhibits replication of the virus and so when a virus would normally try to reproduce itself, this drug inserts itself into that process and then stops viral replication, so it stops reproduction of the virus.

Bill Whitaker: This clinical trial is up and running in the middle of this outbreak.

Dr. Angela Hewlett: I will say this is the fastest clinical trial that I've ever seen come to-- to fruition in this amount of time.

Bill Whitaker: Ordinarily, how long would it take to get a trial up and running?

Dr. Angela Hewlett: that can range from many months to-- to years.

The maker of the anti-viral, remdesivir, Gilead Sciences in California, is ramping up production to provide multiple clinical trials in the U.S., Asia, and Europe. The U.S. Army also is testing the drug.

With no proven treatments, hundreds of trials of different drugs are underway worldwide. Researchers in the U.S. and China are investigating whether the common anti-malarial drug Chloroquine and related drugs might inhibit the virus. In New York, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals is testing a cocktail of antibodies to see if they can temporarily boost immune systems to fight the virus.

Scripps Research in San Diego is using a robot to go through its extensive library of existing drugs looking for antiviral compounds to send to labs around the world to test if any combination might prove effective in combating the new coronavirus and quell the pandemic.

Kate Broderick: I can't express to you the pressure-- that I personally feel under, and I think the whole scientific community feels under. There's a great deal of responsibility-- in working towards a solution for this outbreak, literally as it's happening.

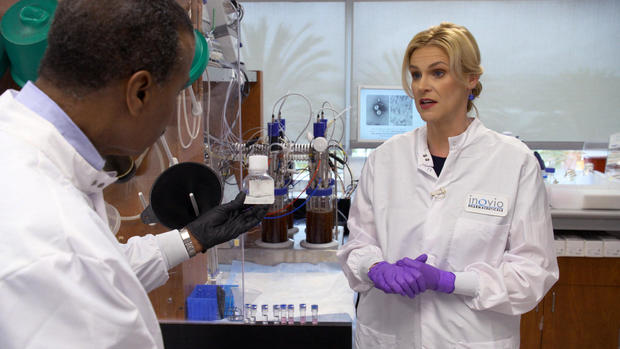

Scottish born Kate Broderick is Senior Vice President of Research and Development at Inovio Pharmaceuticals in San Diego. Employees are working against the clock to create a vaccine to prevent people from ever getting the virus. Inovio is using DNA biotechnology, cutting edge science that has yet to produce a marketable vaccine.

Bill Whitaker: How optimistic are you that this is the solution?

Kate Broderick: I feel very confident in the technology that we've developed here at Inovio. And I feel very cautiously optimistic that our vaccine will be effective when we test it in the clinic.

Inovio has already started testing its vaccine on animals and expects to start human trials next month. The company's race to create a vaccine was triggered by this: the genetic sequence of the new coronavirus. Chinese scientists posted it online just weeks after the outbreak was identified.

Kate Broderick: all we need is that genetic code. So it's just a series of A's, and T's, and C's, and G's that make up the blueprint to the virus. We use a computer algorithm to generate the design of the vaccine. So we plugged in the viral sequence. And after three hours, we had a fully designed vaccine on paper. And then, after that, the stages to manufacture went straight into effect.

Bill Whitaker: Three hours?

Kate Broderick: Yeah, absolutely.

Bill Whitaker: Is that unusually fast?

Kate Broderick: Certainly, if you're thinking of traditional vaccines. They take months to years.

Using the genetic code, Inovio scientists are able to zero in on the part of the deadly virus, these spikes, that attach to human cells. They then recreate that bit of coronavirus DNA in the lab. The synthetic snippet of virus is grown inside bacteria. After sloshing around all night, there are thousands, if not millions of copies of the synthetic DNA. Filtered and processed it looks like this. The vaccine is made from this liquid.

Kate Broderick: Then it's injected into the subject or the patient. And your own body is able to react and mount what we call an immune response against that part of the virus.

Stephen Hoge: I don't feel like we get to choose when an epidemic happens. We just get to decide how we're gonna respond. And what we've decided to do is try and use our platform to bring forward a safe and effective vaccine.

Former emergency room doctor, Stephen Hoge, is president of Moderna, a Boston area biotechnology company also working on a vaccine. We met Dr. Hoge shortly after the CDC recommended social distancing. Teaming up with the NIH, Moderna started human trials last week in Seattle, where the North American outbreak took hold. Forty-five healthy volunteers will receive injections over six weeks and be monitored for a year to see if the vaccine is safe. Moderna started work on the vaccine as soon as China posted the virus genetic sequence online.

Bill Whitaker: So how long did it take you to go from getting this genetic information to actually having a vaccine ready for human trial?

Stephen Hoge: 25 days. It was released to the clinic within 42 days. Dr. Tony Fauci called it the-- I think the world indoor record. But it's definitely faster than we think anybody's-- done before.

Moderna's process pushes the envelope of biotechnology. Its scientists manipulate the genetic code to instruct cells what to do - in this case trigger the body's immune system to fight the new coronavirus.

Stephen Hoge: Once you realize that you can essentially put a software-like program into a cell the opportunities to address human disease are pretty broad.

Bill Whitaker: How did your relatively small biotech get to be the first one to go into human trials?

Stephen Hoge: Some of that has the advantage of the technology we're using. it allows us to move incredibly quickly-- when we have a pandemic situation like the one we're in.

Bill Whitaker: So you-- you have never brought a-- vaccine to market using this technology.

Stephen Hoge: No. We have not.

Bill Whitaker: Have not?

Stephen Hoge: We have not yet.

The National Institutes of Health is collaborating with Moderna to accelerate the development of a coronavirus vaccine. They hope to start a second phase of human trials in a few months.

Bill Whitaker: The whole world is sort of watching and waiting. So if you find that this works, when will people be able to start getting vaccines?

Stephen Hoge: Well, if we're able to show there's a clear benefit-- we're gonna need to be able to make sure that it's accessible to everybody who needs it. And so we've actually already started the investment to scale up supply into the millions of doses. But ultimately what we really need to focus on is generating the clinical data that shows that the vaccine, in fact, does have a benefit, that it's safe and effective.

Bill Whitaker: this is the purest form--

Kate Broderick: This is-- this is the purest form of the DNA.

Kate Broderick of Inovio told us technology is accelerating vaccine development, but it's no match for people's expectations.

Bill Whitaker: what is the realistic timeline for this vaccine being administered to the public?

Kate Broderick: We're hoping to have our vaccine tested in what we call a large, phase two trial by the end of the year, which would be potentially hundreds, if not thousands, of subjects being treated. But to have it rolled out to the public is likely to take longer than that.

Bill Whitaker: So the best case scenario is more than a year. Any way to speed up that process?

Kate Broderick: Really, I-- I have to say, we're going as absolutely fast as we possibly can.

With the number of people with the virus growing exponentially and deaths climbing inexorably that timeline just doesn't seem fast enough. With so much human suffering, hospitals in the U.S., Europe and Japan have given several hundred desperate patients the experimental antiviral drug, remdesivir, for what is called compassionate use. That's the drug being studied in clinical trial at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Dr. Angela Hewlett: We wanna make sure that, you know, we're not giving-- drugs to people that could have side effects.

Bill Whitaker: Now I know you don't know who's getting the drug and who's getting the placebo. But from what you've observed of the patients who are in the trial, what have you seen?

Dr. Angela Hewlett: So we have seen patients improve.

Bill Whitaker: You have?

Dr. Angela Hewlett: but it-- it's hard to tell if they would've just gotten better on their own, or if was due to the drug. And that's the reason that we really need to study this drug in this fashion.

Director of the CDC, Dr. Robert Redfield, told Congress this month we should know in a matter of weeks whether remdesivir is effective. But until a proven treatment and vaccine are available to fight this pandemic, doctors and researchers will keep working at a fevered pitch.

Bill Whitaker: Is this like a race to get to a vaccine?

Stephen Hoge: not really.

Bill Whitaker: How would you describe it?

Stephen Hoge: there's a lot of fear out there right now. And there is a competition. But it's not between the companies. It's between all of us and the virus. It's not us and them. It's us versus it. And the only way we're gonna beat the coronavirus is all working together. No one group, no one company can possibly expect to do this alone.

Produced by Marc Lieberman and Ali Rawaf. Edited by April Wilson. Broadcast associate, Emilio Almonte.