Scientists: Genes, not sun, behind redheads' increased melanoma risk

Redheads have long been known to be at a higher risk for melanoma, the deadliest type of skin cancer, because their fair and sometimes freckly skin provides less natural protection against UV radiation from the sun - or so doctors had thought.

New research shows that genetic factors of the skin pigment that's predominantly found in redheads may be what's to blame for the increased melanoma risk.

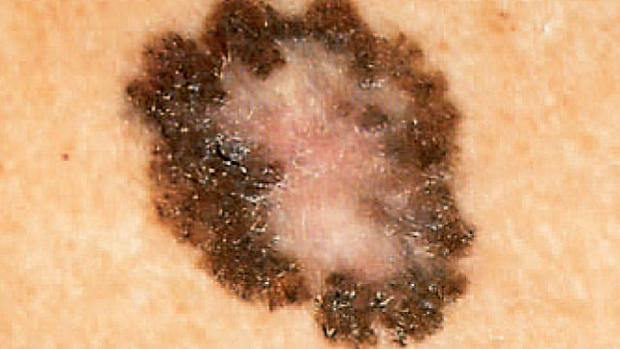

Melanoma is the leading cause of death from skin disease, with more than 76,000 cases expected to be diagnosed in 2012 in addition to nearly 9,200 deaths caused by the cancer.

"We've known for a long time that people with red hair and fair skin have the highest melanoma risk of any skin type," study author Dr. David Fisher, chief of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in a written statement. The new findings "may provide an opportunity to develop better sunscreens and other measures that directly address this pigmentation-associated risk while continuing to protect against UV radiation, which remains our first line of defense against melanoma and other skin cancers," he said.

Fisher's study is published in the Oct 31 issue of Nature.

Human skin contains different types of the pigment melanin, a natural substance that gives the skin its color. There's a dark brown/black form called eumelanin which is predominantly found in those with dark hair or skin, and also a lighter red/blond pigment called pheomelanin, which is the predominant pigment in individuals with red hair, freckles and fair skin.

- Melanoma on rise in young women: Why?

- Skin cancer risk reduced by taking aspirin, ibuprofen, study shows

- Study: Tanning beds cause 170K skin cancer cases yearly

According to the researchers, skin type alone can't explain the rise in melanoma risk among redheads because this increased risk has also seen been seen in skin areas not directly exposed to sun. They tested that theory on two strains of mice that were genetically identical, except one group was bred to have a gene that would give mice more dark-colored pigment and the other group was bred to possess the pigment-producing gene that causes red hair and fair skin in humans.

The researchers used a method to activate a melanoma-causing gene that typically requires UV radiation to create melanoma cancer cells in a lab setting. However, they were surprised to find half of the red mice had developed melanoma within months without UV exposure, compared with only a few dark mice.

Next the researchers wanted to see whether the red pigment itself may cause cancer, testing it on a group of "albino redheads," which were fair-skinned mice who had their pigment production genetically disabled. They found that by completely removing the so-called "red-pigment pathway," the mice were completely protected against melanoma.

The researchers say melanoma risk for redheads might instead be caused by "oxidative damage," from molecules called reactive oxygen species (ROS) which damage cells' DNA. The researchers found higher levels of DNA damage caused by ROS in the skin of red mice, but not in the albino redhead mice.

"Right now we're excited to have a new clue to help better understand this mystery behind melanoma, which we have always hoped could be a preventable disease," Fisher said. "The risk for people with this skin type has not changed, but now we know that blocking UV radiation - which continues to be essential - may not be enough."

Since sunscreen may not offer full protection, the researchers recommend that redheads be especially vigilant looking for changes in their skin, and to never hesitate to get checked out by a dermatologist.

"The big danger here is that somebody will say, 'Oh, well if I can't do anything about it, then I can go to a suntanning salon and go tanning on the beach and just call it fate.' That's not the case," Dr. Meenhard Herlyn, director of the Wistar Institute Melanoma Research Center in Philadelphia, told The Los Angeles Times. "One still has to be very conscientious about not getting a sunburn and getting the damage."

Eugene Healy, a clinical dermatologist at the University of Southampton, U.K., however downplayed the findings to Nature News. He said while the mechanism reported in the study is interesting, it is probably a less common melanoma trigger than UV radiation. "You almost never see melanoma, for example, on the buttocks," said Healy.