Scientists find world's oldest stone tools

Scientists working in a remote region of Kenya have found stone tools dating back 3.3 million years, making them the oldest ever used by our human ancestors.

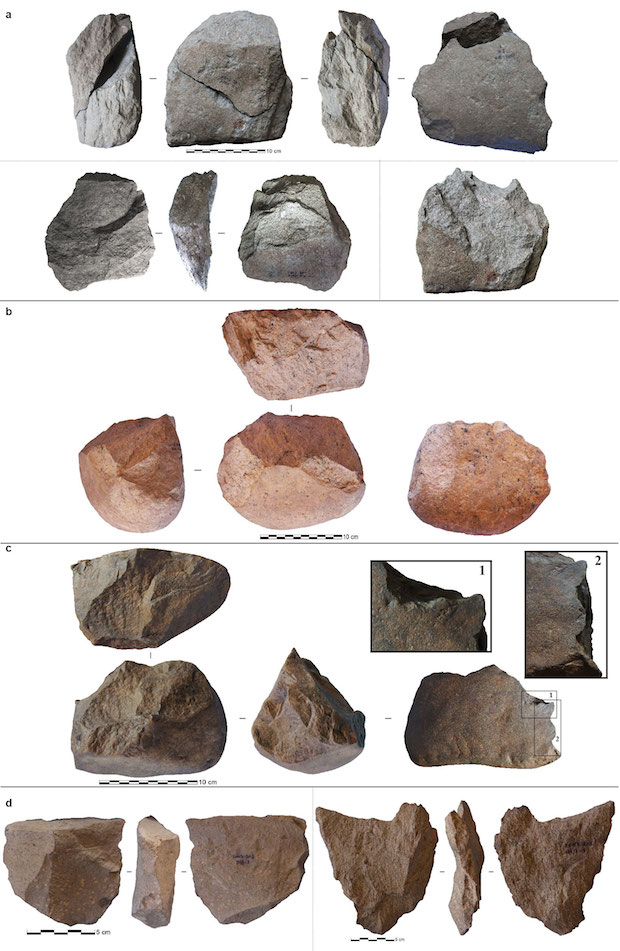

The collection of razor-edged and round rocks the size of softballs and even bowling balls pushes the known date of such tools back by 700,000 years and would suggest that our ancestors were converting them into pounding or cutting tools long before our genus homo appeared. They are much simpler than the more modern stone tools, which had a much broader range of uses.

The tools "shed light on an unexpected and previously unknown period of hominin behavior and can tell us a lot about cognitive development in our ancestors that we can't understand from fossils alone," said lead author Sonia Harmand, of the Turkana Basin Institute at Stony Brook University and the Université Paris Ouest Nanterre.

Calling the discoveries at the archeological site named Lomekwian 3 a "new beginning to the known archeological record," the researchers detailing the findings Wednesday in a Nature study suggest this would be first evidence that an even earlier group of proto-humans may have had the thinking abilities needed to figure out how to make sharp-edged tools.

"The whole site's surprising, it just rewrites the book on a lot of things that we thought were true," said geologist Chris Lepre of the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and Rutgers University, a co-author of the paper who precisely dated the artifacts.

The researchers admit they can't say for sure who made the tools. But earlier finds suggest a possible answer.

The skull of a 3.3-million-year-old hominin, Kenyanthropus platytops, was found in 1999 about a kilometer from the tool site. A K. platyops tooth and a bone from a skull were discovered a few hundred meters away, and an as-yet unidentified tooth has been found about 100 meters away.

The precise family tree of modern humans is contentious, and so far, no one knows exactly how K. platyops relates to other hominin species. Kenyanthropus predates the earliest known Homo species by a half a million years. This species could have made the tools or the toolmaker could have been some other species from the same era, such as Australopithecus afarensis, or even an undiscovered early type of Homo.

"It could be Kenyanthropus, It could be Australpithecus afarensis," Lepre said. "It's like if you come across a crime scene and you find a murder and there are 300 people in the building. You need evidence to link that person the crime. It's the same way here. We need more evidence."

Anthropologist Louis Leakey first found stone tools more than 80 years ago in East Africa's Olduvai Gorge - the oldest of these so-called Oldowan tools were later dated to 2.6 million years old. Leakey and his wife later found bones there from a species they named Homo habilis or the "handy man." That convinced most anthropologists that our lineage alone took the cognitive leap to create tools - a theory that was directly linked to climate change and the spread of the savannah grasslands.

But in 2010, Shannon McPherron and his team announced they had found evidence - dents in small animal bones from Dikika, Ethiopia - that stone tools were used by hunters at least 3.39 million years ago. Critics dismissed the find, suggesting that the marks came from animal teeth or simply wear and tear.

The latest tools would seem to pretty much put that debate to rest - and support the 2010 findings.

"The publication in 2010 of the marked Dikika specimens was a turning point in paleoanthropology, because it got researchers thinking in new ways about the origins and significance of stone tool use in our earliest ancestors," Emory University's Jessica C. Thompson, who was among those who conducted a blind test to confirm the 2010 findings and believes the latest tools are the oldest.

"It got them out looking for sites like Lomekwi 3," she said. "And it got them thinking carefully about the fundamental shifts in diet that took place at this point in our evolution, because using tools to butcher bones from large antelope is something that is unique to the human lineage."

Richard Potts, director of the Human Origins Program at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, who was not involved in the latest study, saw the tools during a visit to Kenya in February and came away convinced they were "definitely purposeful modification of the stones by the hominins" 3.3 million years ago.

"The capabilities of our ancestors and the environmental forces leading to early stone technology are a great scientific mystery," Potts said, adding that the newly dated tools "begin to lift the veil on that mystery, at an earlier time than expected."

At the desert site of the latest discovery that borders Sudan and Ethiopia, researchers were able to date a layer of volcanic ash below the tool site, which set a "floor" on the site's age. It matched ash elsewhere that had been dated to about 3.3 million years ago.

To more precisely date the tools, Lepre and co-author and Lamont-Doherty colleague Dennis Kent examined magnetic minerals beneath, around and above the spots where the tools were found.

"We essentially have a magnetic tape recorder that records the magnetic field ... the music of the outer core," Kent said. "By tracing the variations in the polarity of the samples, they dated the site to 3.33 million to 3.11 million years."

But what were the tools used for?

The initial thought was that they would have been used to cut meat off animal carcasses or smashing their bones. But the size and markings of the newly discovered tools "suggest they were doing something different as well, especially if they were in a more wooded environment with access to various plant resources," Lewis said.

Among the possibilities is that the tools were used for breaking open nuts or tubers or bashing open dead logs to get at insects.

"The tools are much larger than later Oldowan tools, and we can see from the scars left on them when they were being made that the techniques used were more rudimentary, requiring holding the stone in two hands or resting the stone on an anvil when hitting it with a hammerstone," Harmand said. "Some of the gestures involved are reminiscent of those used by chimpanzees when they use stones to break open nuts."

Potts agreed, saying "the researchers are wise to have given a different name - Lomekwian - to this type of stone alteration in order to distinguish it from the oldest definite stone tools known up until now, which are more sophisticated in how early humans flaked the stone. "

"Many of the rocks are large enough to have been used as anvils held on the ground. Such anvils are known to have been used by early humans and even by living chimpanzees and other primates," he said.

What struck Thompson about the tools was that they were "much closer to what we would expect at the dawn of this technology."

"But they are indeed purposefully made stone tools," she said. "This not only means that our ancestors were making stone tools at a time when our brains and bodies were still ape-like in many ways, but that there is much more to be learned about how those ancient creatures were spending their day-to-day lives."

Potts said more research was need to done to determine exactly why the stones were hit together. The other outstanding question, he said, was whether there was continuity from "the 3.3 million-year-old stone alteration described in the new study and the 2.6 million-year-old Oldowan stone technology."

"Were the stone-using and stone-altering capabilities of Australopithecus something that switched on and off?" Potts queried. "In other words, was the toolmaking activity at Lomekwi a short-lived behavior that might have occurred off and on without it spreading or proliferating as you would expect of a new and consistently useful adaptation to the environment? Or is there indeed continuity yet to be discovered over the 700,000 years between the Lomekwi stone-altering behavior and Oldowan technology?"