Scientists crack genetic code of Black Death germ, Yersinia pestis

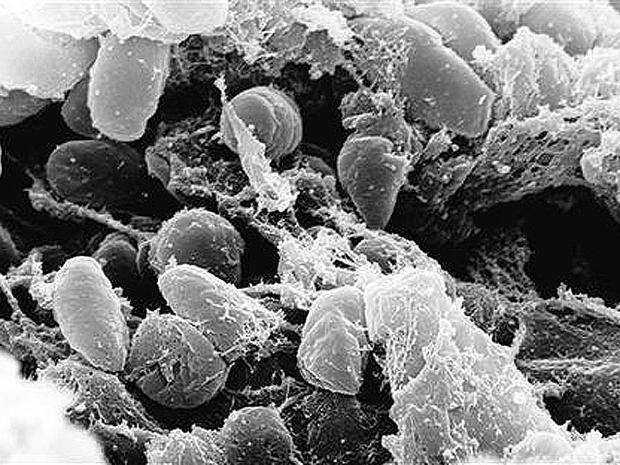

(CBS/AP) Using DNA taken from centuries-old skeletons, scientists have cracked the genetic code of the bacterium that caused the Black Death, one of history's worst plagues. They found that the germ, Yersinia pestis, is almost identical to germs that are around today.

There are only a few dozen changes among the more than 4 million building blocks of DNA, according to a study published online Wednesday in the journal Nature.

That suggests that the Black Death, or plague, was so lethal for reasons beyond its DNA, study authors said. It had to do with the circumstances of the world back then.

In its day, the disease killed 30 million to 50 million people - about 1 in 3 Europeans. It struck at a time when the climate was suddenly cooling, in the midst of war and famine, and people were moving into closer quarters where the disease could spread easily, scientists say. And it was likely the first time this particular disease had hit humans, suggesting that their immune defenses against the germ were lacking.

"It was literally like the four horseman of the apocalypse that rained on Europe," said study author Johannes Krause of Germany's University of Tubingen. "People literally thought it was the end of the world."

In devastating the population, Yersinia changed the human immune system, wiping out people who couldn't deal with the disease and leaving the stronger to survive, said study co-author Hendrik Poinar of McMaster University in Ontario.

Today, simple antibiotics like tetracycline can beat the plague bacterium, which seems to lack the properties that enable other germs to become drug resistant, Poinar said. Plus, advances in medical treatment, coupled with improved sanitation, put humanity in a better position. And there's an immune system protection we mostly have now, Poinar said.

"I think we're in a good state," Poinar said. "The reason we do so well is that conditions are so different."

People still get the disease, usually from fleas from rodents or other animals, but not often. Worldwide, there are around 2,000 cases a year, mostly in rural areas, with a handful popping up in remote parts of the U.S., according to the CDC. Earlier this year, two people in New Mexico were diagnosed with plague. In 1992, a Colorado veterinarian died from a more recent strain, one that scientists used heavily in their study.

To get the original Black Death DNA, scientists played dentist to dozens of skeletons.

During the epidemic in the 14th Century, about 2,500 London-area victims of the disease were buried near the Tower of London. It was excavated in the mid-1980s with 600 individual skeletons moved to the Museum of London, said study co-author Kirsten Bos, also of McMaster University. She removed 40 of those teeth, drilled into the pulp inside the teeth and got "this dark black powdery type material" which likely was dried blood that included bacterial DNA.

When she was done, Bos returned the teeth, minus a little DNA, to the skeletons at the museum.

When the same scientists first tried mapping the bacterium's genetic makeup, it appeared to be a distinctly different germ than what is around today. But part of that was a reflection of working with 660-year-old DNA and newer, more refined techniques revealed fewer difference between the early day and modern Y. pestis than between a mother and daughter, Krause said.

That's a surprising result, but the work was well done and makes sense, said Julian Parkhill, a disease genome expert at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Britain. Parkhill was not involved in the research but has studied the germ.

"Getting an effectively complete genome sequence of a bacterium that lived nearly 700 years ago is incredibly exciting," Parkhill said.

The CDC has more on Yersinia pestis and plague.