"Putin can't kill me": Russians fleeing call to fight in Ukraine find safety, but no welcome in Georgia

For weeks at the northern border of Georgia, lines of cars have stretched for miles as hundreds of thousands seek to escape the fighting in Ukraine. But these escapees aren't Ukrainians, they're Russians, fleeing President Vladimir Putin's so-called "partial mobilization" — a call to fight in his war.

Georgian officials say more than 10,000 Russians are crossing into the former Soviet republic every day, mostly heading to the capital Tbilisi. Relieved to avoid the bloodbath of their own country's making, about 100 new arrivals crowd into a room rented by a support group organized by the NGO Emigration for Action.

Here, they get advice on how to open a bank account, get a cell phone, and other tips to get by in this tiny country the size of West Virginia. First, however, they get a bit of history: The organization starts the meeting by telling the true history of Russia's 2008 invasion of neighboring Georgia, for all the Russians who likely weren't aware.

Outside the meeting, one recent arrival gives CBS News only his first name, Aleksei, to protect his family back at home. He takes us down Tbilisi's winding streets, which are now lined with cars bearing Russian license plates.

"This one is mine," he says. "It took me seven days to drive here from Moscow, with little more than my guitar." Better to have fled carrying that than be forced to carry a rifle into Ukraine, he adds.

We descend into a nearby basement dwelling that's been converted into a shelter for Aleksei and 12 other Russians.

One of them, Skobar, is cooking lunch in the kitchen. About two weeks ago, he received a letter ordering him to report for military training. He decided to catch a domestic flight from Moscow to the border with Georgia instead, and then ride a bike across the frontier to skip the long lines of cars.

"It was really surprising because I am a student, I am only 21 years old, and I've got nothing to do with any army stuff in my past," he said, fidgeting nervously with a rubber band. "It got me panicking, because I don't want to go to the army and go to war and die and kill people."

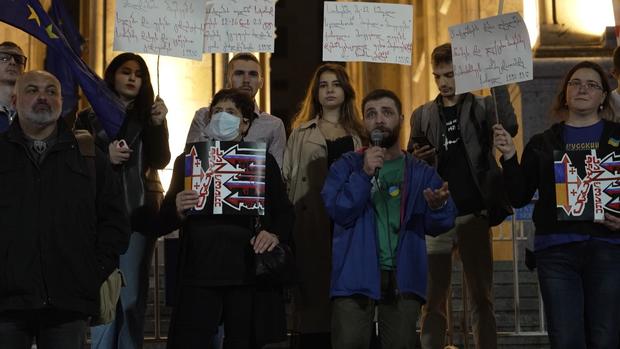

But that same day, at an anti-Putin rally in the capital Tbilisi, Georgians voice fears that the Russian draft-dodgers are really a Trojan horse. The demonstrators see the hundreds of thousands of Russians who have arrived, virtually overnight, as another form of Russian invasion, and they demand the border be closed.

"They are not welcome here until they say that Russia is an occupier," says Nick, a protester who declined to use his last name. "They are not welcome here, they must know that they are not home."

Georgia is no stranger to Russian invasion. Putin attacked by land, air and sea in 2008 — to protect Russians living in Georgia, he said. To this day, 20% of the country remains occupied by Russia. So, who's to say Georgia won't become the next Ukraine, wonders Nick.

"Because we know how Putin starts wars. One day he can come and say, 'Russian citizens who live in Georgia, we need to protect them from Georgians.'"

But morale levels in Putin's army have never been lower, following staggering defeats in the south and east of Ukraine. His troops are retreating, and surrendering ground daily.

Multiple videos posted on social media show conscripts so desperate to dodge the draft, that they're breaking their own arms and legs. Such is the terror that the Russian people have of both the war, and their own government, says Skobar.

"The fear, it's not something rational. It's not something logical. One day you wake up and start to feel it," he says.

Skobar is relieved to be in Georgia, even if not all Georgians are happy to see him.

"When I say that I'm Russian, I feel like I'm telling people some secret about me, a terrible secret. But I'm in safety, that Putin can't kill me or that I'm not in jail, I'm not arrested. Of course, I don't have work and I live in a refugee center, but I'm living with beautiful people, everybody is democratic, liberal and I just feel comfortable."

But when asked how long he expects to stay here, he fights to hold back tears.

"I don't know," he says. "I want to live in Moscow. I want to work in my old job [as a bartender], I want to be with my family and my girlfriend. So, I guess I will turn back when Vladimir Putin will be dead. And I will be just fine with this."