Russia-Ukraine standoff: What you need to know now

Russia has massed well over 100,000 troops near its own border with Ukraine and in neighboring Belarus, leaving the country surrounded on three sides. The buildup and position of those forces has drawn warnings from the White House that Russian President Vladimir Putin could order an attack "any time," and may well do so before the end of this week.

The U.S. has poured military hardware into Ukraine and contributed to a buildup of NATO forces in Eastern Europe in response. Russia and NATO are both carrying out military exercises in the region and demanding that the other party step back first from the brink of war.

Along with European partners and the G7, the U.S. has warned that any Russian invasion of Ukraine would bring "swift and severe costs" for Moscow, in the form of sanctions.

U.S. and European leaders have also warned that a full Russian invasion of Ukraine could result in 100,000 civilian deaths and change the world in fundamental ways. But neither side has abandoned diplomacy yet.

Here's what you need to know about the standoff on the border between Russia and the democracies of Europe.

What's happening now?

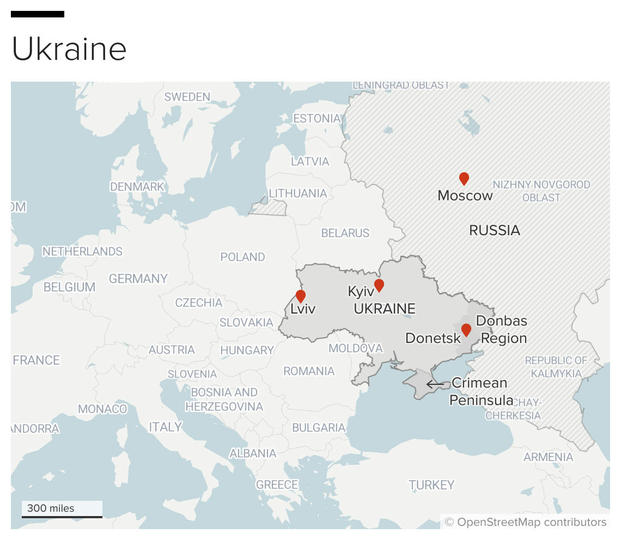

The Russian forces have gathered along Ukraine's northern, eastern and southern borders. U.S. officials tell CBS News that Russia now has at least 80% of the forces in place that it would need to launch a full-scale invasion, and that Russia is expected to launch some form of attack against Ukraine by the end of this week.

Russia insists it has no intention of invading Ukraine and has dismissed the U.S. warnings as "hysteria."

The West points to huge Russian military exercises just across Ukraine's borders as evidence of its aggression. NATO and Ukraine have responded by carrying out their own war games close to Russian territory.

Russia has said that a massive joint drill it's holding with ally Belarus, on Ukraine's northern border, will end on February 20 and that the 30,000 Russian forces taking part will come home when it's over. But on February 14, a U.S. official told CBS News national security correspondent David Martin that Russian troops near Ukraine's border had begun moving into "attack positions."

The Russian defense minister said earlier the same day that some of Russia's military exercises in the region had already concluded and that others would wrap up in the coming days. It was a vague statement, and U.S. officials reported no movements of Russian forces away from Ukraine's borders.

Secretary Antony Blinken announced Monday the U.S. is temporarily moving embassy operations in Ukraine from Kyiv to Lviv, near the country's western border, due to the "dramatic acceleration in the buildup of Russian forces."

Why all the concern about Russia?

The fear of Russian aggression is based on precedent: Russian forces invaded eastern Ukraine in 2014. Putin claimed the assault was merely a defense of ethnic Russians who live in Ukraine's eastern Donbas region, who've never supported the country's relatively new, pro-Western government.

But Putin used the invasion to very literally claim part of Ukraine for Russia, unilaterally annexing the Crimean Peninsula. The annexation is not recognized by the international community, but Russia has indisputably controlled the territory since 2014.

Since the annexation, a proxy war has simmered in Donbas between Russian-backed forces and the Ukrainian government. A 2015 peace deal largely ended the major battles, but the fighting has continued, and left more than 14,000 people dead in the process, according to the Ukrainian government.

What does Putin want?

Russia's strongman leader speaks often of the ethnic ties between Russia and Ukraine and warns against NATO expanding further eastward toward his borders. Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union before declaring its independence in 1991.

As CBS News' David Martin reported in January, Putin's objective is to keep Ukraine — the second-largest country on the continent — from making common cause with the democracies of Europe.

"What motivates Putin," former NATO Ambassador Ivo Daalder told CBS News, "is a concern about the independence of Ukraine — a worry that a functioning, successful, prosperous democracy in Ukraine poses a direct threat to his rule, because it will give people in Russia the idea that they, too, could enjoy what Ukraine enjoys, and rise up against his autocratic rule."

To end the current standoff, Putin has demanded that NATO rule out admitting any new members from among the former Soviet states — most importantly, Ukraine — and that NATO forces pull back from positions in other countries near Russia.

The U.S. and NATO have rejected the demand to preclude any new members as a non-starter, but they have voiced willingness to negotiate over military deployments and openness with exercises in the region, along with other trust-building measures. The U.S. government is waiting for a formal response from the Kremlin to proposals handed from Washington to Russia weeks ago.

Many analysts believe Putin's objective is to erode confidence in Ukraine's government so it can be replaced with a new pro-Russian regime, and that he's using the external threat of military action, along with plausibly deniable actions like cyberattacks, to achieve that.

How has Ukraine responded?

Ukraine has made the quest for NATO membership a cornerstone of its national security policy, and it has refused to back down from that ambition, though even before the current Russian military buildup there was no discussion of Ukraine being admitted to the alliance anytime soon.

While many Ukrainians, especially in the country's east, are pro-Russian, Ukrainians ousted their last pro-Russia president in 2014 and have consistently elected pro-Western politicians since.

The country has responded to the current standoff by readying its forces to confront any Russian invasion, including with huge shipments of U.S. weapons, civilian defense units and ongoing military exercises near its border with Russian ally Belarus.

Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has urged his nation to remain calm, and most Ukrainians — tempered by almost eight years of conflict in the country's east with the Russian-backed separatists — have done so. Despite the White House warnings of a possible imminent invasion, there has been no panic or hysteria, not even stockpiling, in the capital, Kyiv.

Why is it America's problem?

As Ukraine is not a NATO member, the U.S. and most of its European allies have ruled out sending troops into the country to help defend its territory. Instead, they have provided military hardware, cash, and diplomatic support.

President Biden and Secretary of State Antony Blinken have held multiple calls with Russian officials, including a phone call between Mr. Biden and Putin on February 13. So far, the direct conversations have yielded no breakthroughs.

The U.S. interest in rebuffing Russia's aggression is difficult to explain in terms of goods or American lives: Ukraine is not a significant trading partner, and a threat to its territory or sovereignty poses no direct threat to that of the United States.

But the world's most powerful democracies have struggled for years to keep Putin's myriad nefarious actions in check — from claiming Crimea, to poisoning dissidents on British soil and blocking U.N. sanctions against the Assad regime in Syria.

As Putin seeks now to deepen Russia's ties with China, another powerful nation eager to portray the Western model of democracy as past its prime, the U.S. has a clear interest in turning back his latest and boldest effort to drive a wedge between NATO members.

–Eleanor Watson, Olivia Gazis, David Martin, Ed O'Keefe, Sara Cook, Margaret Brennan and Christina Ruffini contributed reporting.