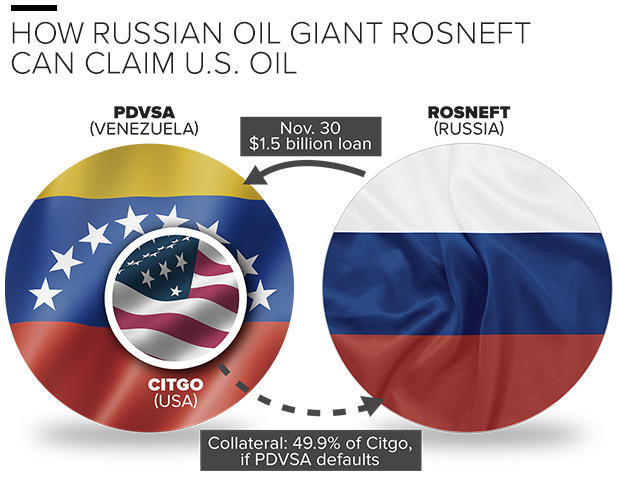

How Russian oil giant Rosneft could claim U.S. oil

Rosneft, an oil corporation majority-owned by the Russian government, says it has the right to claim an ownership stake in U.S. oil company Citgo Petroleum if Citgo’s cash-strapped parent company defaults on billions in loans, according to a lien Rosneft recently filed in Delaware. If that claim succeeds, Rosneft, which is run by one of President Vladimir Putin’s closest allies, would own a sizable chunk of a company that is among the 10 largest petroleum refiners in America.

Russian ownership of a large portion of a U.S.-based oil company would be unprecedented, according to experts contacted by CBS News. Those experts also emphasize that the White House has the power to block the deal -- either on national security grounds or simply by leaving in place Obama administration sanctions against Russia.

Citgo’s parent company, the Venezuela state-owned PDVSA, pledged a 49.9 percent stake in Citgo to Rosneft as collateral for a $1.5 billion loan signed on Nov. 30. That same day, attorneys for Rosneft filed the lien with the Delaware Department of State, asserting that Rosneft — whose CEO, Igor Sechin, has long been considered Putin’s right-hand man — would claim the collateralized 49.9 percent if the struggling Venezuelan debtor defaults or folds.

A PDVSA default in the near future would not be a surprise, said Praveen Kumar, who is the executive director of the Gutierrez Energy Management Institute at the University of Houston’s Bauer College of Business.

In fact, credit rating agency Fitch reported in January that a default at PDVSA is probable. And in September, another credit rating agency, Standard & Poor’s, downgraded PDVSA to a CCC rating -- near the bottom of the junk-bond ladder -- after a complex bond swap that Standard & Poor’s called “tantamount to default.” Meanwhile, Venezuela, reeling from the global collapse in oil prices since 2014, has less than $10.7 billion remaining in foreign reserves, down from $30 billion six years ago, according to the latest data from the country’s central bank.

Kumar, whose research focuses on energy finance, said a default would leave the door open for Rosneft to seize the promised stake in Citgo, a company whose U.S. holdings include three refineries and three pipelines.

“If [PDVSA] gets in trouble and if Rosneft thinks it’s in their best interest to grab Citgo’s assets, they’re going to grab the assets,” Kumar said.

The players involved make the deal particularly newsworthy, said Philip Jordan, an oil, gas and mineral law partner at the Dallas-based firm Gray Reed & McGraw.

“If there was a default under the loan, Rosneft would have ownership on that stock,” Jordan said. “It’s not unusual from a legal perspective -- companies use stock as collateral all the time -- but it’s very unusual from a geopolitical perspective to have a Russian company and a Venezuelan company doing business in Delaware [where Citgo Holdings is based].”

PDVSA is believed to owe billions of dollars to corporations that sued after the Venezuelan government seized international oil and mining operations based in the country a decade ago during President Hugo Chavez’s reign. The Rosneft lien was included as an exhibit in a federal lawsuit for alleged unpaid debts filed by ConocoPhillips, another oil company, against PDVSA. The Houston-based corporation estimates in the court filing that PDVSA owes it “multiple billions of dollars” in damages.

ConocoPhillips added Rosneft to the lawsuit after the Russian oil company and PDVSA agreed to the loan.

“The key to open all the locks here is the Venezuelan government’s desperation for cash,” Kumar said. He and other experts said PDVSA has been siphoning money from its American company to the Venezuelan government, which for more than a decade has used oil profits to subsidize social commitments.

Both ConocoPhillips and Crystallex, a Canadian mining company that is also owed more than $1 billion from PDVSA, have asked the Delaware federal court to cancel Rosneft’s lien.

Just over 50 percent of Rosneft is owned by Rosneftegaz, a Russian state agency run by Sechin, the Rosneft CEO. A 19.5 percent stake in the company was purchased in December by a consortium of investors that include the Anglo-Swiss commodities producer and trader Glencore, the Qatar Investment Authority and anonymous investors based in the Cayman Islands. The rest is owned by British oil company BP and Russia’s National Settlement Depository, a division of the Moscow stock exchange.

Representatives of PDVSA, Citgo and Rosneft did not reply to requests for comment on this story.

While the terms of Rosneft’s loan to PDVSA could lead it to own nearly half of Citgo — the other 50.1 percent would remain under PDVSA control — there are two major roadblocks in its way.

U.S. sanctions against Russia

Rosneft, with $86 billion in annual revenue, is the world’s largest public oil company in terms of reserves and output. But it is barred from acquiring U.S. holdings because of sanctions imposed by former President Barack Obama’s administration after Russia annexed the Ukrainian territory of Crimea in March 2014.

However, as a candidate for president, Donald Trump expressed an openness to relaxing those sanctions, which include a ban on business transactions with dozens of companies and officials, including Rosneft and CEO Sechin.

A former British spy’s 35-page dossier about alleged communications between Trump associates and a Russian official, which has gained credibility among law enforcement, includes claims that in July Sechin met with energy industry investor Carter Page, who at the time was a foreign policy adviser to the Trump presidential campaign. Page and Russian officials have denied the meeting occurred.

Mr. Trump said in a January interview with the Times of London that he would consider removing sanctions as part of a nuclear arms reduction deal. And ExxonMobil lobbied Congress about the sanctions while Secretary of State Rex Tillerson was the company’s chief executive, arguing they were harmful to U.S. business interests.

In late December, U.S. surveillance of Russian officials picked up soon-to-be National Security Adviser Michael Flynn’s voice on a call with Sergey Kislyak, the Russian ambassador to the United States, discussing Obama administration sanctions on Russia. It is not clear which sanctions were discussed and Flynn resigned on Feb. 13, following media reports about the call. The New York Times later reported that in early February two Trump business associates met with a Ukrainian politician about a plan to lift Russian sanctions as part of an effort to solve the violent conflict simmering between Ukraine and Russia.

Ilya Ponomarev, a Russian politician and former vice president of Yukos — which was Russia’s largest oil and gas corporation before the early 2000s, when the Russian government seized its assets, absorbing them into Rosneft — said in an interview with CBS News that Rosneft is likely betting the sanctions will be lifted.

“Right now you have Trump and he seems favorable to Russia, and so they think in a year maybe the sanctions are gone, and maybe it goes through,” said Ponomarev, during a phone call from Kiev, Ukraine, where he lives in self-imposed exile after being the lone member of Russia’s State Duma to vote against the annexation of Crimea.

Ponomarev noted that although Venezuela and Russia have long-standing friendly ties, it is unusual that they would agree to a deal involving U.S. assets.

“U.S. markets are interesting for Russian companies, but they stay away because of the sanctions,” Ponomarev said. “Generally, Rosneft is pretty cautious internationally, [because] it’s a state actor. It’s like a state ministry.”

But even if sanctions are lifted, there would still be one more hurdle that Rosneft would have to jump to assert ownership over PDVSA’s collateral after a default: the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, or CFIUS.

What is CFIUS?

When foreign companies make major investments in American properties, each side is expected to voluntarily file a notice with the White House committee known as CFIUS, a collection of nine Presidential Cabinet members who review the national security implications of foreign investments in U.S. companies. Its chair is the U.S. Treasury Secretary.

CFIUS has never previously had so many members with ties to the oil industry. Tillerson, the former CEO of ExxonMobil, was closing in on an oil exploration deal with Rosneft reportedly worth in the tens of billions when the Obama administration announced the Crimea sanctions. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross purchased through his investment firm hundreds of millions of dollars in energy debt in 2016, according to the Wall Street Journal. Energy Secretary Rick Perry has been on the board of directors of two pipeline companies. All three have left their previous positions and taken steps to divest their business interests in the energy industry.

Experts interviewed by CBS News said companies involved in CFIUS reviews are not told if a committee member with potential conflicts has recused himself.

“We don’t know because of the nature of the CFIUS process, which is confidential,” said Mark Plotkin, a partner at the Washington law firm Covington & Burling, who has handled CFIUS cases

Representatives of each CFIUS member agency, as well as the White House, directed CBS News to the Treasury Department for comment when asked whether the department head would support any transaction that would allow ownership of U.S. oil properties by a Russian state-owned firm. A spokesperson for Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin declined to comment beyond noting that “information filed with CFIUS may not be disclosed to the public.”

In 2014, the most recent year for which data are available, CFIUS reviewed 147 filings, rejecting one. Another 12 filings were withdrawn during the review process.

While rejections are rare, there have been cases in which foreign state-operated companies have withdrawn their bids due to political pressure. In 2005, for instance, the Chinese state-owned oil and gas company CNOOC cancelled its $18.5 billion bid for U.S. oil company Unocal after members of Congress sought to extend CFIUS’ review of the case.

Every expert contacted by CBS News predicted the Rosneft transaction would meet similar, if not fiercer opposition.