"This is not a human life": New struggles for Rohingya refugees

NEW DELHI -- Life for the 14,000 Rohingya Muslim refugees crammed into slums in the Indian capital is a daily struggle. There is little in the way of sanitation. Even electricity can be hard to come by.

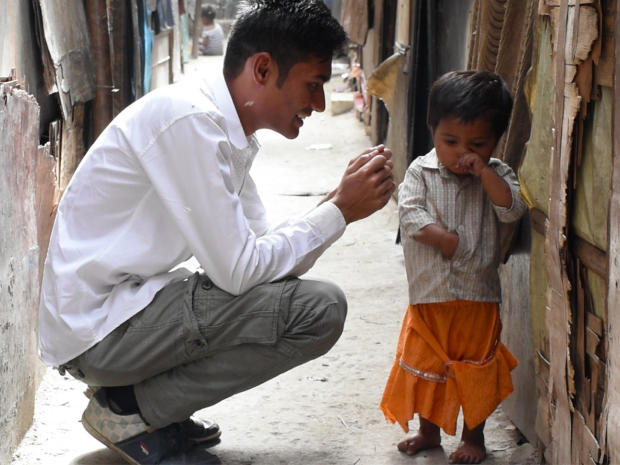

Row after row of small shanties -- most, just simple bamboo frames covered with tarps -- are crammed onto low-lying pieces of land in New Delhi. There are no proper roads, just narrow tracks weaving through the fetid maze of shacks.

In one slum, home to about 50 Rohingya refugee families, there are just two water pumps and a couple toilets for all to share. Human and animal waste litters the alleyways, drawing armies of flies and mosquitoes in the steaming Delhi summers when temperatures regularly top 110 degrees.

"Health and sanitation are the key challenges here," Muhammad Haroon told CBS News. He lives in the slum with his children, including a son born just three months ago. "Our children fall ill due to mosquito bites and the unhygienic conditions here."

The United Nations refugee agency helps the Rohingya, who fled alleged government-backed persecution in their home country of Myanmar. The UNHCR helps the refugees gain access to public education and health facilities in India, but many of the kids don't actually go to school, and if they do, they often drop out within months.

Most adults in the slums don't have a stable income. A few have opened shops funded by UNHCR, like Haroon, but most work as laborers, earning less than $5 a day -- and they don't get work every day.

"This is not a human life," refugee Ali Johar told CBS News. "The basic human rights; a proper place to stay, toilet, water, are missing."

And those are just the immediate concerns.

"Feeding us to the sharks"

In early April, Indian media reports suggested the government was working on a plan to try to arrest and deport the Rohingya refugees on the grounds they were illegal immigrants. Some officials within the Indian security and intelligence agencies believe the Rohinya are prone to radicalization by Muslim extremist groups.

But it may be difficult -- if not impossible -- for India to deport the Rohingya, even if such planning is afoot.

A senior UNHCR official in India told CBS News it was "considered part of customary international law, binding on all states" that registered refugees cannot be sent back to their home countries if they could be subjected to persecution.

The official also noted that India is party to several international human rights conventions, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, Convention on the Rights of the Child, which would make a mass-deportation impossible.

"If India sends us back to Myanmar, we will face much more persecution than we have already faced," Johar told CBS News. "It will be like feeding us to the sharks."

Just as they did at home, the Rohingya face regular threats in the country to which they have fled. A trade body in Jammu, northern India, has threatened to "identify and kill" Rohingya Muslims and Bangladeshi immigrants in the city if they're not deported.

"Habit of lying"

"Why doesn't the world help solve our issue with the Myanmar government, so that we won't need to flee to any other country?" Johar wondered as he spoke to CBS News.

Myanmar's de-facto leader, Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi spent decades under house arrest in Myanmar as an outspoken critic of the country's ruling military junta, which seized power in the early 1960s.

Significant reforms, much lauded by the West, saw her released in 2015 and her political party won huge support in elections that year. Her rise to power, after years as an outspoken but imprisoned advocate for democracy, brought new hope that the contentious issue of the Rohingya might finally be addressed.

In a recent interview, however, Suu Kyi denied that her country's Rohingya Muslim minority is deliberately targeted.

"Ethnic cleansing is too strong an expression" she said, suggesting violence in the western Rakhine state also included, "Muslims killings Muslims."

Johar believes Myanmar's government is still, "in the habit of lying to the international community."

"When Suu Kyi was under detention, she told the world, 'please use your liberty to promote ours,'" Johar said. "I want to tell her today, 'now you are free, please use your freedom to promote ours.'"

Johar does not, however, intend to just wait for others to help his people.

When he first arrived in India he worked as a laborer on construction sites for about six months, but then managed to finish school in Delhi with the help of the UNHCR. Now he's studying to earn a bachelor's degree from the University of Delhi, and he intends to become a lawyer, to fight for his people.