Scientists discover Mars-sized rogue planet aimlessly zooming through the Milky Way

Scientists have discovered a lonely orphaned planet wandering through the Milky Way with no parent star to guide it — a "rogue" planet, stuck in endless darkness with no days, nights, or gravitational siblings to keep it company.

It's possible our galaxy is filled to the brim with these rogue planets, but this one is particularly unusual for one special reason: it is the smallest found to date — even smaller than Earth — with a mass similar to Mars.

Scientists have found over 4,000 "extrasolar" planets, also known as exoplanets, which are planets that orbits a star other than the sun. Many exoplanets — for example, one where it rains liquid iron — bear no resemblance to planets in our solar system, but they all have one shared trait: they all orbit a star.

But just a few years ago, astronomers in Poland found evidence of free-floating planets, unattached gravitationally to a star, in the Milky Way galaxy. In a new study, the same astronomers have now found the smallest such planet to date.

Exoplanets are difficult to spot, typically found only by observing the light from their host stars. Because free-floating planets have no parent star and emit almost no radiation, astronomers have to take a different approach to find them.

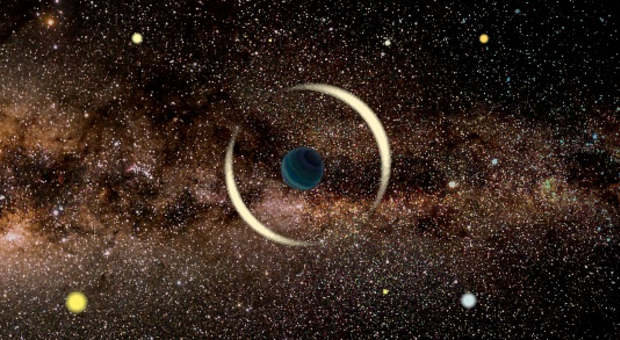

Rogue planets are spotted using gravitational microlensing, a result of Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity. In this case, the gravity of the planet (lens) acts as a sort of magnifying glass, able to bend the light of a bright star (source) behind it so that an observer on Earth can detect its presence.

"The observer will measure a short brightening of the source star," lead author Dr. Przemek Mroz, a postdoctoral scholar at the California Institute of Technology, said in a news release Thursday. "Chances of observing microlensing are extremely slim because three objects—source, lens, and observer—must be nearly perfectly aligned. If we observed only one source star, we would have to wait almost a million year to see the source being microlensed."

Researchers on the lookout for these events are monitoring hundreds of millions of stars in the center of the galaxy, which provides the highest chances of microlensing.

The Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment survey, led by Warsaw University astronomers, is one of the largest and longest sky surveys, operating for over 28 years. Currently using a telescope at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, the astronomers look to the galaxy's center on clear nights, in search of changes in the brightness of stars.

Because this technique relies only on the brightness of the source and not the lens, it allows astronomers to spot faint or dark objects — like rogue planets.

Measuring the duration of such an event, in addition to the shape of its light curve, can provide an estimation for the mass of the object astronomers are searching for. While most observed events, caused by stars, last several days, small planets only provide a window of a few hours.

In this case, OGLE-2016-BLG-1928, the shortest microlensing event ever recorded, lasted just 42 minutes. Based on the event, astronomers estimated the planet to have a Mars-like mass and found it to be rogue.

"When we first spotted this event, it was clear that it must have been caused by an extremely tiny object," said co-author Dr. Radoslaw Poleski from the Astronomical Observatory of the University of Warsaw. "If the lens were orbiting a star, we would detect its presence in the light curve of the event. We can rule out the planet having a star within about 8 astronomical units (the astronomical unit is the distance between the Earth and the sun)."

It's not totally clear why these rogue planets have no parent stars, but scientists don't think the planets had any say in the matter. Rather, they may have originally formed as "ordinary" planets — only to be kicked out of their parent systems after gravitational interactions with other planets.

NASA is currently constructing the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, scheduled to start operations in the mid-2020s. Studying these free-floating planets can help astronomers better understand the unstable histories of young planetary systems — including our own solar system.