Which industries use the most robots?

Wondering what work will look like when the robots take over? Look no further than the auto industry, which accounts for almost half of industrial robots in the U.S., a recent analysis from the Brookings Institution shows.

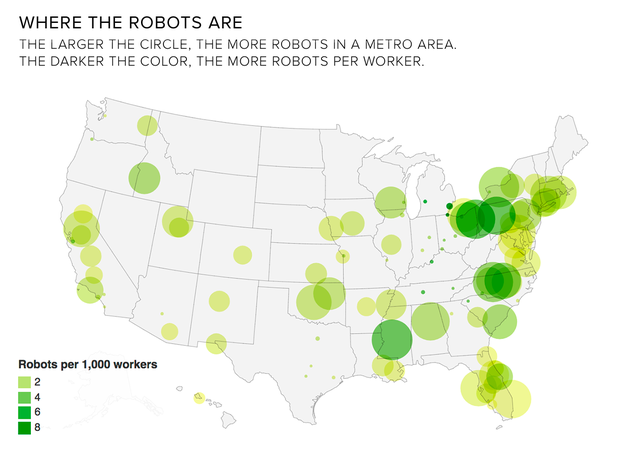

Industrial robots "are burning welds, painting cars, assembling products, handling materials or packaging things in just 10 states." in the Midwest and South, led by Michigan, Ohio and Indiana, according to the analysis.

Of the more than 233,000 robots used in the U.S. in 2015, Michigan accounted for almost 12 percent, Ohio 8.7 percent and Indiana 8.3 percent. By contrast, the entire West makes up just 13 percent of industrial robots. Other "significant" users include electronics, rubber and plastics industries.

Of the largest metropolitan areas, robot "intensity" is most concentrated in the Detroit area, with more than 8.5 industrial robots in place per 1,000 workers. Industrial robots tripled in Toledo, Ohio; Grand Rapids, Michigan; Louisville, Kentucky; and Nashville, Tennessee between 2010 and 2015, according to Brookings.

Industrial companies have been adding robots for decades. But investment climbed after the 2008 financial crisis as corporations sought to be more productive and competitive, Mark Muro, a Brookings senior fellow and policy director who wrote about the findings, said in an interview.

Automaker employment climbed after the financial crisis, when the government bailed out General Motors, as the industry pushed to be more competitive globally. U.S. Department of Labor statistics show a steady increase in auto employment since 2010, leveling off this year. Without embracing automation, the industry may have been less competitive and smaller, Muro said.

"While the map is familiar, that's an auto map. I was surprised how much that is true," Muro said, adding that the numbers might show robot use that was "more diffuse" across industries. Electronics manufacturing came in second, while chemicals and plastics production, where growth is speeding up in states along the Gulf of Mexico, was third, he said.

Another finding sticks out: A dozen smaller cities and towns had more robots per 1,000 people, or density, than any large metropolitan area, including four towns in Indiana, Tuscaloosa, Alabama and Spartanburg, South Carolina.

"Small places turn out to be deeply enmeshed in global and technological trends of our time," Muro said. "Places that are company towns with heavy reliance on a single plant run by a single company are automating furiously."

That could be a another reason robots may have played a role in the 2016 presidential election, with the average red state "intensity" of 2.5 robots per 1,000 workers. Blue states had an average of 1.1, according to the analysis.

Brookings used data from the International Federation of Robotics. The analysis follows a paper released in March from economists at MIT and Boston University. That paper was controversial, according to Brookings, "in its modeling of large negative effects of robots on employment and wages" but the "underlying robot data appear sound."

Brookings didn't analyze employment data.

But stay tuned -- the think tank later this year plans to release another map that's "more predictive" across dozens of industries and more than 550 occupations where robot use "may be most disruptive," Muro said.