The government whistleblower who says the Trump administration's coronavirus response has cost lives

Dr. Rick Bright is the highest-ranking government scientist to charge the federal government's response to the coronavirus pandemic has been slow and chaotic. He says it has prioritized politics over science, and has cost people their lives.

It has cost Dr. Bright his job. In April, he was removed from a top position in the Department of Health and Human Services, and transferred to what he considers a position of less stature and responsibility. Dr. Bright has filed a whistleblower complaint running over 300 pages.

President Trump has called Rick bright a disgruntled employee. In congressional testimony on Thursday, Bright claimed the government retaliated against him for telling the truth about the depth of the crisis.

Bright at congressional hearing: Our window of opportunity is closing. If we fail to improve our response now based on science, I fear the pandemic will get worse and be prolonged.

Until a month ago, Dr. Rick Bright led BARDA, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, a federal agency to which Congress has handed more than $5 billion to fund vaccine development, new antiviral drugs, and badly-needed medical supplies.

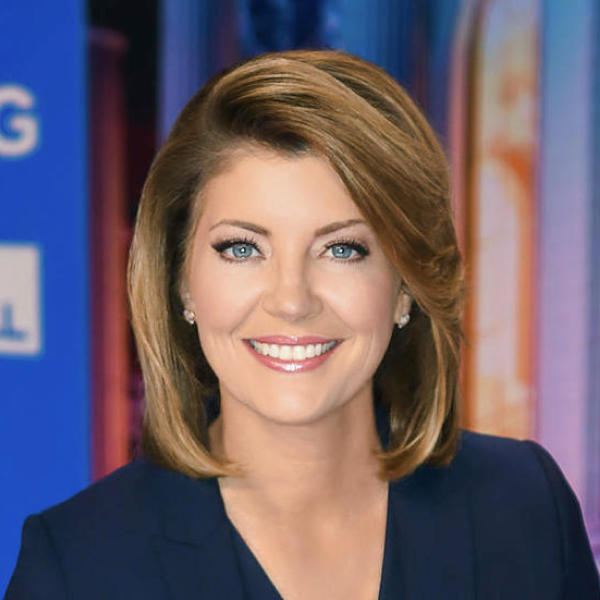

Norah O'Donnell: What is BARDA's mission? And how does it fit in the response to a Coronavirus like this?

Rick Bright: We focus on chemical threats, biological threats such as anthrax, nuclear threats, radiological threats, pandemic influenza and emerging infectious diseases.

He still speaks in the present tense, but Rick Bright isn't running BARDA anymore. The reasons trace back to the very first days of January, when he heard of a new coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China.

Norah O'Donnell: When did you first realize that this virus might be different? That this was the big one?

Rick Bright: Well, I have been trained my entire life to recognize these outbreaks and recognize viruses. I have a Ph.D. in virology. I knew that all of the signs for a pandemic were present. A novel virus, infecting people, causing significant mortality and spreading. So all the signs were there. It was just a matter of time before that virus then jumped and left China and appeared in other countries.

Norah O'Donnell: In early January when you were concerned about this virus, were other government officials on alert?

Rick Bright: I believe my concerns were shared by other scientists in the government. And I believe the NIH was also moving very quickly to start some research in developing a vaccine and starting a clinical trial for an antiviral drug. What struck me though was my sense of urgency didn't seem to prevail across all of HHS.

Bright says that lack of urgency started with the boss of his department, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar. He recalls a meeting Azar chaired on January 23 to discuss the coronavirus.

Rick Bright: I was the only person in the room, however, that said, "We're going to need vaccines and diagnostics and drugs. It's going to take a while and we need to get started."

Norah O'Donnell: You were the only one to raise that?

Rick Bright: Yes.

Norah O'Donnell: In your complaint, you said that Secretary Azar was intent on downplaying this catastrophic threat. Why would he do that?

Rick Bright: You know, I don't know why he would do that.

President Trump was also downplaying the threat. He said this at an event in Michigan on January 30.

President Trump at January 30 event: We think we have it very well under control. We have very little problem in this country at this moment – five.

Rick Bright: Remember, the entire leadership was focused on containment. There was a belief that we could contain this virus and keep it out of the United States. Containment doesn't work. Containment does buy time. It could slow. It very well could slow the spread. But while you're slowing the spread, you better be doing something in parallel to be prepared for when that virus breaks out. That was my job.

Bright says he was well-equipped to do that job because just five months before the new virus emerged, his and other key agencies had concluded an exercise titled Crimson Contagion, premised on the exact idea of a fast-spreading virus originating in china.

Norah O'Donnell: What did Crimson Contagion teach you about fighting pandemics? What were the lessons?

Rick Bright: They were lessons about shortages on critical supplies such as personal protective equipment, such as masks, N95 masks, gowns, goggles. And there were lessons about the need for funding.

Norah O'Donnell: You had practiced this.

Rick Bright: We had drilled. We had practiced. We've been through Ebola, we've been through Zika, we've been through H1N1. This was not a new thing for us. We knew exactly what to do.

Bright says one big lesson from Crimson Contagion was that the entire U.S. medical supply chain would be understocked and under stress for vaccines, testing, and personal protective equipment.

Rick Bright: I had industry manufacturers, industry reps sending me emails almost every day, raising alarm bells that the supply chain was running dry, that America and the world was in trouble.

Mike Bowen was one of those people. He had been warning Rick Bright and BARDA for years. His small Texas company, Prestige Ameritech, is one of just a few that still make surgical and N95 masks in the U.S. Over the last 15 years, he says, 90% percent of the manufacturing has shifted abroad, where masks are cheaper to make.

Norah O'Donnell: How long have you been telling anyone who would listen that, once a pandemic hits, that America would face a big problem?

Mike Bowen: Since 2007. And for 13 years, we told-- we told the story that a pandemic was going to come, the mask supply was going to collapse, and foreign health officials were going to cut off masks to the United States, and that's exactly what happened.

Bowen's factory near Fort Worth had several mask production lines sitting idle, and on January 22, he sent Rick Bright an email offering to reactivate those lines, which could produce 7 million masks a month, but said he could only do it "with government help."

Norah O'Donnell: Mike Bowen was offering to ramp up production. He's like, "I have the factory. I can make more masks." Did you have the authority to say, "Yes, let's do it?"

Rick Bright: I did not, not in BARDA. I had the authority to push that need up into the right department in the-- in-- HHS, in our department. And I did so almost daily for a period of time.

Norah O'Donnell: In fact, on January 25, you wrote your colleagues that, "The mask situation seems to be of concern, and we have been receiving warnings for over a week." How did they respond?

Rick Bright: Passively. They responded with a, "Thank you for notification. We'll talk to the manufacturers ourselves and-- take appropriate action when it's needed."

Norah O'Donnell: A day later, on January 26th, Mike Bowen was even more blunt in an email to you, saying this, "The U.S. mask supply is at imminent risk. Rick, I think we're in deep sh-- ."

Rick Bright: He was exactly right. Mike Bowen saw this coming and was doing everything he could do to get the attention of the U.S. government to get us to act.

Though it took nearly two months, the U.S. government finally did act, ordering 500 million masks. A push for that came from Peter Navarro, President Trump's director of trade and manufacturing policy, who has long been concerned about American industrial production shifting abroad, especially to China.

Norah O'Donnell: President Bush didn't fix the problem of manufacturing like this going overseas. President Obama didn't. And neither has President Trump. Why is this so hard?

Rick Bright: It's actually not hard. It does take a strategy. It does take a commitment. It does take some investment, as well. And again, it's not just about masks.

Norah O'Donnell: You're telling me we've completely offshored our ability to respond to a pandemic.

Rick Bright: We have offshored a lot of our industry for critical supplies, critical health care supplies, and critical medicines to save money.

In March, as hospitals were beginning to swell with critically ill COVID-19 patients, the search was on for any and all possible treatments.

President Trump: Hydroxychloroquine, I don't know it's looking like it's having some good results. I hope that that would be a phenomenal thing.

The president began to tout the potential of a drug combination that he said in a tweet on March 21 had a, "real chance to be one of the biggest game changers in the history of medicine."

Norah O'Donnell: Did you ever think that hydroxychloroquine would be a game changer?

Rick Bright: No. Never. And the limited data available told us that it could be dangerous. It could have negative side effects. And it could even lead to death.

According to Bright's whistleblower complaint, "on March 23… Dr. Bright received an urgent directive… passed down from the White House, to drop everything and make" the drug "widely available to the American public."

Norah O'Donnell: What was the reaction of your lead coronavirus scientist when you got this directive, "You've got to drop everything?"

Rick Bright: I believe his expression was at the time that, you know, we've been hit by a bus.

Bright says his team tried to limit access to the drugs to hospital patients only, and he shared his concerns with a reporter. On April 21, he was reassigned to what he considered a lesser role at the National Institutes of Health.

Norah O'Donnell: You believe you were retaliated against because you raised concerns about hydroxychloroquine?

Rick Bright: Yes. I do. I believe my last ditch effort to protect Americans from that drug was the final straw that they used and believed was essential to push me out.

HHS firmly disputes that, claiming in a statement that Bright's "whistleblower complaint is filled with one-sided arguments and misinformation." And Secretary Alex Azar said it was Bright who made the request for an emergency use authorization, or EUA, for hydroxychloroquine.

Alex Azar at press conference: Dr. Bright literally signed the application for FDA authorization of it. Literally, he's the sponsor of it.

Norah O'Donnell: I mean, you say you were retaliated against. But at the same time, you did sign the EUA.

Rick Bright: I was given a directive. I didn't have a choice, other than to leave at that time. And I went along and signed that letter knowing that we had contained access to that drug.

Bright at congressional hearing: The American healthcare system is being taxed to the limit…

As Rick Bright was testifying before Congress on Thursday, President Trump weighed in.

President Trump: I tell you what. I watched this guy for a little while this morning. To me he's nothing more than a really disgruntled, unhappy person.

Norah O'Donnell: The president called you a disgruntled employee.

Rick Bright: I am not disgruntled. I am frustrated at a lack of leadership. I am frustrated at a lack of urgency to get a head start on developing lifesaving tools for Americans. I'm frustrated at our inability to be heard as scientists. Those things frustrate me.

Rick Bright knows he won't be BARDA's director again, but he says he will report to his new position at the NIH by the end of May, and hopes to continue to speak out about the coronavirus pandemic.

Rick Bright: We don't yet have a national strategy to respond fully to this pandemic. The best scientists that we have in our government who are working really hard to try to figure this out aren't getting that clear, cohesive leadership, strategic plan message yet. Until they get that, it's still gonna be chaotic.

Produced by Keith Sharman, Rome Hartman and Adam Verdugo. Associate producers, Alex J. Diamond, Sara Kuzmarov, Sheena Samu and Margaret Hynds. Edited by Sean Kelly.