Rewind: Parting the sea with Venice's Project Moses

Amsterdam is a city known for its canals. Waterways encircle the city's historic center like a kind of belt, providing picturesque views of boats and urban reflections. Even though Amsterdam sits almost entirely below sea level, the city never floods. As Bill Whitaker reports this week on 60 Minutes, the Dutch have taken extraordinary precautions to prevent flooding and allocate more than a billion dollars each year to manage their flood infrastructure.

The other city of canals is a different story.

Venice, too, is famous for its characteristic waterways. But it's also known for its narrow brick streets inadvertently turning into small rivers more than 100 times a year. In 2001, correspondent Bob Simon reported on a new effort aimed at preventing this deluge of water, a system of gates then called Project Moses.

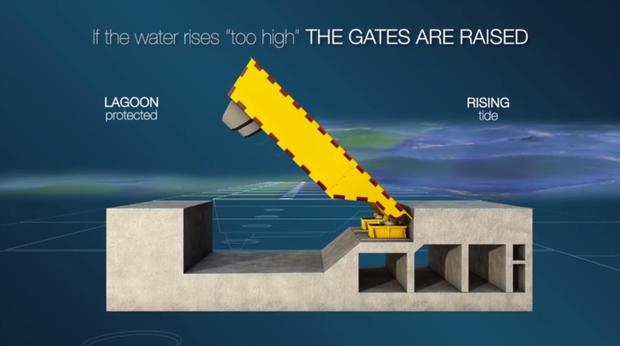

The gates are similar to the Dutch system. In the Netherlands, two enormous arms seal off the Rhine River and Rotterdam. In Venice, the system will employ mobile gates at the three openings to the lagoon which surrounds Venice. The gates can sit idle in the water during low tide, then during storms, they can be raised to provide a barrier between the lagoon and the Adriatic Sea.

But as Simon reported, Project Moses needed a miracle — squabbling between Italy's politicians had kept the system mired in debate for years.

"If Nero fiddled while Rome burned, the Italians have been fiddling while Venice drowns," Simon reported. "It took nearly 20 years for Project Moses to be drawn up, and Italy has been arguing about it for the past 10. And Venetians … fear it will take another disastrous flood to shake Italy's politicians."

Simon spoke with Andrea Rinaldo, a professor who was part of a panel of experts brought in to evaluate Project Moses. Simon was frank: Did Rinaldo think Project Moses would ever happen?

"No, I don't think so," Rinaldo said. "Unfortunately, I don't think so. I don't think you're going to march forward, not an inch."

Project Moses may not be marching, but it's at least still somewhat afloat. Today, it's called MOSE, an acronym for Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico, or "Experimental Electromechanical Module." It still alludes to Moses, or Mosè in Italian, whose biblical narrative includes the parting of the Red Sea — much like MOSE's 78 gates are intended to do.

Work on MOSE began in 2003, more than 20 years after the proposal was submitted — but after countless delays, it's still incomplete. According to the Italian newspaper La Stampa, the project, which has already cost 5.5 billion euros (approximately $6.5 billion), is now expected to be completed in 2022. For comparison, the Dutch gates took just six years to build and cost $500 million.

Here's a look at MOSE today.

Simon understood the consequences of delay in 2001. He quoted Marcel Proust, who wrote, "When I came to Venice, my dream became my address."

"He, like every worshiper of Venice, realized that only the Italians could have built this city," Simon said, "and perhaps equally, only the Italians can sit by and watch it disappear."