Retirement income scorecard: Systematic withdrawals

(MoneyWatch) Continuing our look at how to assess your future retirement income, let's turn our attention to "systematic withdrawals," which are one of three ways to generate a paycheck from the retirement savings you've stashed away. (For more background on the three methods, you may want to review this recent post: "3 ways to turn your IRA and 401(k) into a lifetime retirement paycheck.")

Financial planners and writers will tell you that if you invest in a balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds, withdraw 4 percent each year for retirement income and give yourself an annual raise to account for inflation, there's roughly a 90 percent chance that your money will last for at least 30 years. This is what's behind the 4 percent rule.

- 3 ways to turn your IRA and 401(k) into a lifetime retirement paycheck

- Retirement income scorecard: interest and dividends

- Your most critical retirement planning challenge

Retirement income generator (RIG) No. 2: Systematic withdrawals

The 4 percent rule is a good starting point for determining an appropriate withdrawal rate. But if you fall into one of the following two categories, you may want to consider withdrawing amounts of less than 4 percent:

- If your retirement investments are actively managed and incur investment expenses of more than 50 basis points (0.50 percent), over the long run you may fall short of the net rates of return that justify the 4 percent rule.

- If you're married, both you and your spouse are healthy and you retire in your early to mid-60s, there's a good chance that one of you will live for more than 30 years.

If either of these statements applies to you, you may want to consider payout rates on your retirement income of 3 or 3 1/2 percent.

In addition, some financial analysts, among them Wade Pfau, say that the analyses supporting the 4 percent rule are based on a period of U.S. history that may have been a remarkably good time for stock and bond returns. But it's possible that future returns on stocks and bonds won't be able to support a 4 percent withdrawal rate. If that's how you see it, you may want to lower your rate of withdrawal.

On the other hand, you may want to consider a higher withdrawal rate if you're willing to accept the chance of running out of money before you die, or if you're willing to curb your withdrawals down the road should your investments sour. In fact, many analysts believe it doesn't make sense to devise a withdrawal strategy when you first retire if you're not going to adjust that strategy to reflect changing conditions in the course of your retirement. In short, setting the appropriate withdrawal rate is both art and science, and there's no single right answer that works for everybody.

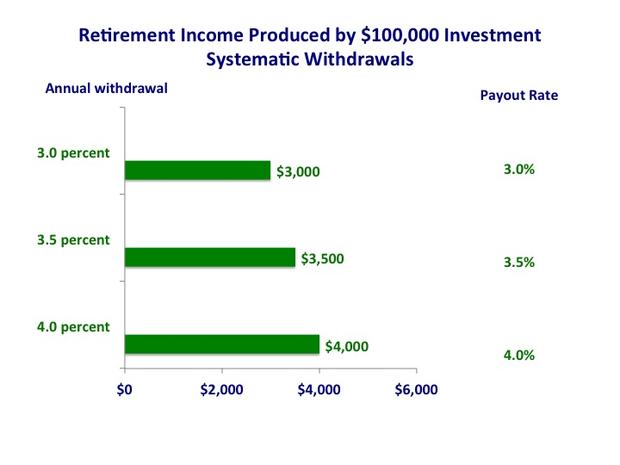

For the purpose of comparing this strategy with other methods of producing retirement income, here's a simple table comparing payout amounts for $100,000 in retirement savings at three different rates.

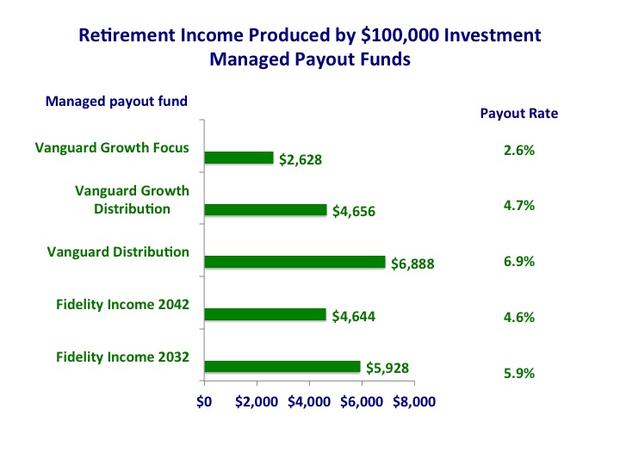

Now let's look at managed payout funds offered by mutual fund companies. Vanguard offers managed payout funds, and Fidelity offers so-called income replacement funds. These funds invest in balanced portfolios of stocks and bonds, and pay a monthly retirement income that includes interest, dividends and principal payments. Here's a comparison of annual retirement paychecks generated by these funds and their payout rates as of July 2013.

The payouts from Vanguard funds have increased since my last retirement income scorecard in January, but the payouts from the Fidelity funds are unchanged.

Why are the payouts from most of these funds are higher than those from the simple managed payout rules shown previously? There are a few reasons.

With the simple managed payout rule, your monthly income should never decrease, even with poor investment returns. You start with a low payout rate so that you can withstand possible future unfavorable investment returns. Your monthly income from the Vanguard and Fidelity managed payout funds can decrease in the future if returns head south.

The Fidelity funds are designed to be exhausted at their target date (thus the snarky nickname for this investment, "target death funds"). The Vanguard funds, however, are meant to last throughout one's life, but that's not guaranteed.

Also, note that the Vanguard and Fidelity funds each have different asset allocations, depending on their growth goals, which helps to explain the different payout rates.

Clearly, there are differences in the way systematic withdrawals can work, and you'll need to spend some time learning about the different strategies and features. It's not enough to just pick the method or fund that generates the highest retirement income. And you would do well to recognize that systematic withdrawals require the most ongoing attention of the three different ways to generate retirement income.

The retirement income data in the charts above represent pretax income amounts. It's important to recognize that federal and state income taxes will have a significant effect on your after-tax income and should be taken into account. The income taxes you pay will vary depending on whether your retirement savings have previously been invested pretax in traditional IRA or 401(k) accounts or have been invested after-tax, such as in a Roth IRA. Your eligibility for special tax treatment on capital gains, ordinary dividends or municipal bonds will also come into play.

My next post will offer a retirement income scorecard for RIG No. 3, immediate annuities.