Relocating a Frank Lloyd Wright house

An empty clearing about 20 miles west of Duluth, Minnesota, used to be Peter and Julene McKinney's living room. They lost it not to a fire, a storm, or a foreclosure, but to progress.

"The first few days were a little tough, you know, watching your home be taken apart," Peter said.

Julene remembered seeing "a bulldozer in the kitchen."

They had tried to sell it for a decade. No takers. The pine trees did their best to hide the strip mall and the Walmart that had sprouted up across the street, but they couldn't hide the reality; the peace and quiet of the land had gone.

"I think Frank Lloyd Wright always said when you find the perfect land, go 10 miles further, and in this case it was probably pretty accurate," Julene said.

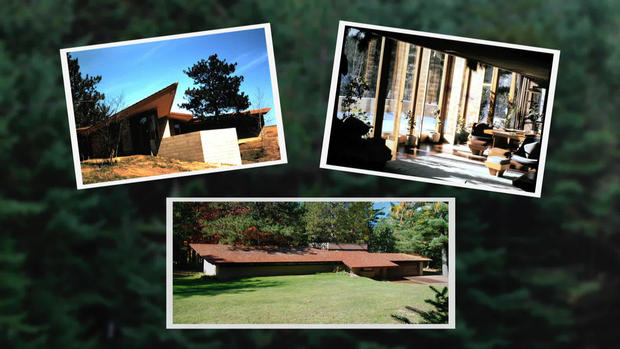

Famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright had designed that house for Peter's grandparents, Emma and Ray Lindholm, back in the mid-1950s. It had all of Wright's signatures – the low profile, the big windows, the cantilevered roof. It even had a name: Mäntylä, which is Finnish for "of the pines."

But now it was gone.

"I had a lot of really good memories there," said Julene, wiping away tears.

We've been creating a lot of memories in our homes lately – they've become our offices, our schools, our safe havens. What a luxury it would be to return to the world in something like the McKinneys' Frank Lloyd Wright house.

Well, there's one place where you can do just that, thanks to Tom Papinchak and his wife, Heather.

Correspondent Lee Cowan asked, "How did you interest in Frank Lloyd Wright start?"

"For myself," Tom replied, "it's childhood memory."

Back in 2003, Papinchak stumbled on 130 acres about an hour outside Pittsburgh. On that land, surrounded by woods, were two remote houses built by one of Wright's apprentices, Peter Berndtson.

They had names, too: the Balter House and the Blum House, slices of mid-century architecture that Tom, a licensed contractor, thought deserved a second chance. So, he bought the land … and both houses.

Cowan asked Heather, "So, when he came to you with the idea of buying 130 acres with two houses on it that you weren't going to live in?"

Tom said, "I don't think it was an idea; I think I told her after the fact!"

"Yes, we're going to take this leap of faith, and make it happen," Heather said.

Tom worked tirelessly to restore both of them, and eventually started offering tours. It went so well, it gave Tom another idea: If people would come all the way out here just to look at a home inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright, maybe they'd want to spend the night in one, too.

Heather said, "Our first overnight guest were from Tel Aviv, and we're from a very small coal mining town, so to meet people from so far away was really amazing."

It is "no frills" – there's no spa, no workout room, no valet parking here. It's just a step back in time, in a place Heather and Tom called Polymath Park – polymath meaning a person of encyclopedic learning.

Busloads of guests and tourists started to arrive, and Heather and Tom soon earned a reputation as preservationists with the space and the know-how to foster wayward homes.

And soon, another one came up for adoption. It was in Lisle, Illinois, called the Duncan House, and it was actually designed by Wright himself. To save it from the wrecking ball, it had been disassembled and put into shipping containers for storage. It was a giant jigsaw puzzle that Tom wasn't entirely sure he could put back together.

Cowan asked, "How did you even start?"

"It was three of us: me, God, and Frank Lloyd Wright!" he laughed. "That's kind of how it began, as a leap of faith for sure. I've always had this inner stirring to make a difference. And I think that was kind of the beginning of that, realizing that, 'Okay, this is my path.'"

Guests couldn't wait to stay overnight – it was booked solid from the get-go. They were so busy they needed more room, but Frank Lloyd Wright homes aren't exactly easy to find (or easy to move).

But, remember the McKinneys' lovely Frank Lloyd Wright home that just didn't fit into its surroundings anymore? Bingo.

Tom said, "We sat down on the couch and Peter McKinney says, 'Well, what do you think?' And I said, 'I can do it.' And he said, 'Really?'"

That "House of the Pines" wasn't torn down, it was lovingly deconstructed by Tom Papinchak and his hand-picked craftsmen. Every nut, bolt, window, door, even the roof tiles were cataloged, wrapped and shipped to Polymath Park.

It would be three long years before Peter and Julene McKinney would see their old house again.

And there it was – standing proudly nearly a thousand miles from where it was originally built.

"It's hard to describe, it's almost like we've never left," Peter said. "It just feels like home immediately."

Julene told Cowan, "The last time I left the house before the deconstruction, I just went in the hall and I put my hand there and I just said, 'Goodbye house, I'm going to see you in Pennsylvania.'

"You kept your promise," Cowan said.

"I did, yeah, and that was one of those moments where you're like, I can't believe we did this!"

The fact that strangers will soon be spending the night in their home doesn't bother them at all. In fact, that's what they hoped for, especially after reactions like this from a German tourist, Rebecca: "Oh my God, coming to stay in a Frank Lloyd Wright house? That's like a dream come true!"

And a dream of a Pennsylvania couple who found a way to share their love of architecture with those who might never get a chance to experience a Frank Lloyd Wright home as a resident, not a passing tourist.

Tom said, "That's what's most gratifying to me, is reading the guest book, just to read their quick paragraph of how it moved them or inspired them in some way."

"Because they get that privilege to live in one for 24 hours?" Cowan asked.

"Exactly," said Heather. "And they get to see the sun setting and the sun rising, and see the light in all the ways that Wright intended."

These few quiet acres at Polymath Park may be just what the doctor ordered – a place where the past, it seems, will always have a home.

For more info:

Story produced by Mark Hudspeth. Editor: George Pozderec.