Reintroducing Yemeni coffee to America

Connoisseurs swear this coffee from a far-off land is, well, good to the last drop. Very, VERY good. And as John Blackstone tells us, for the price, it better be:

Coffee experts call it cupping -- the standardized ritual for evaluating coffee beans.

The beans under scrutiny at Equator Coffee, a specialty roaster in San Rafael, California, have Equator's co-founder Helen Russell reaching for superlatives.

"This is a treat, this is passion, this is history, this is drama, this is the best coffee in the world," she told Blackstone.

It comes from Yemen, a country so racked by war its coffee has been largely out of reach for decades -- until a young man named Mokhtar Alkhanshali decided to go and get it.

"If I knew that I was going to go through a war-torn country, escape bullets and air strikes, and leave on a boat across a giant ocean, I would have never started this journey," he said.

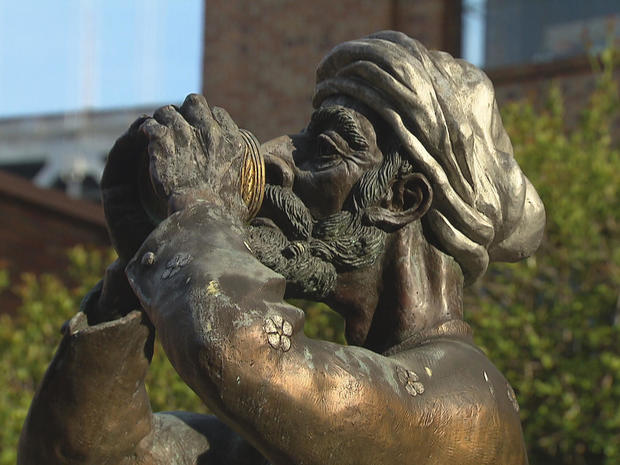

The trip started when he saw a century-old statue in San Francisco: a Yemeni monk with a cup of coffee to his lips … the logo for the Hills Brothers Coffee Company.

"I saw it, [and] I started remembering stories of my grandparents, my mother," Alkhanshali said. "When I was younger my family took me back to Yemen quite a bit. And so I remembered picking coffee cherries with my grandmother."

The connection he felt to coffee drew him back to ancient villages in Yemen, a country his parents left before he was born, a place where for hundreds of years coffee has been grown on steep mountain terraces.

"I went to about 32 different regions across Yemen," Alkhanshali said. "It was a very interesting time for me, because I didn't realize how crazy of a place it was, going through the political instability."

Yemeni farmers are said to have been the first to cultivate coffee. Cut off from the international market for years, their standards had been falling. "So I realized the way it was picked and processed was very arbitrary," Alkhanshali said.

"And so I had to slow down and begin working with them hands-on.

"And that looked like building them raised drying-bed systems, giving them moisture analyzers. But probably the biggest thing was giving them micro loans. The first year we paid for six weddings; they paid us back in coffee cherries."

Getting the coffee out of Yemen with bombs falling forced Alkhanshali to escape in a small boat across the Red Sea, carrying with him coffee beans from the villages.

"Actually when I escaped on the boat, it was a big deal for them," he said. "One village had a huge meeting. And they realized how committed I was for them. And if it wasn't for their hard work and their belief in my vision, I wouldn't be able to do this work."

Back in America, James Freeman, of Blue Bottle coffee, was among the first to taste the beans Alkhanshali had carried out of Yemen.

"It was stunning, stunning coffee," he exclaimed.

And Blue Bottle started selling it at a stunning price: $16 a cup.

Blackstone asked, "When you're offering this coffee at $16 a cup, is it an act of charity to buy it?"

"No," replied Freeman. "No, I think it's an act of sensory pleasure. It has to be an amazing transporting experience for us to be able to justify that price."

Alkhanshali said, "People are willing to pay more for coffees if they know it had a social impact. Luckily like these coffees also are pretty wonderful coffees."

That price begins with farmers in Yemen being paid a fair price, then rises with the cost of transporting the coffee out of the remote mountains and exported from a country in conflict, to a package here in America.

"If I want to help my farmers, I have to make sure their coffees are great," Alkhanshali said. "When someone pays $16 for a cup of coffee, it better be a good coffee!"

See also:

- Brewing Yemeni coffee (from Port of Mokha)

For more info:

- Mokhtar Alkhanshali's Port of Mokha

- Equator Coffees & Teas, San Rafael, Calif.

- Blue Bottle Coffee