Every patient in this experimental drug trial saw their cancer disappear, researchers say

A small clinical trial conducted by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center found that every single rectal cancer patient who received an experimental immunotherapy treatment had their cancer go into remission.

One participant, Sascha Roth, was preparing to travel to Manhattan for weeks of radiation therapy when the results came in, Memorial Sloan Kettering said. That's when doctors gave her the good news: She was now cancer-free.

"I told my family," Roth told The New York Times. "They didn't believe me."

These same remarkable results would be seen in 14 patients to date. The study was published Sunday in the New England Journal of Medicine. All of the patients had rectal cancer in a locally advanced stage, with a rare mutation called mismatch repair deficiency (MMRd).

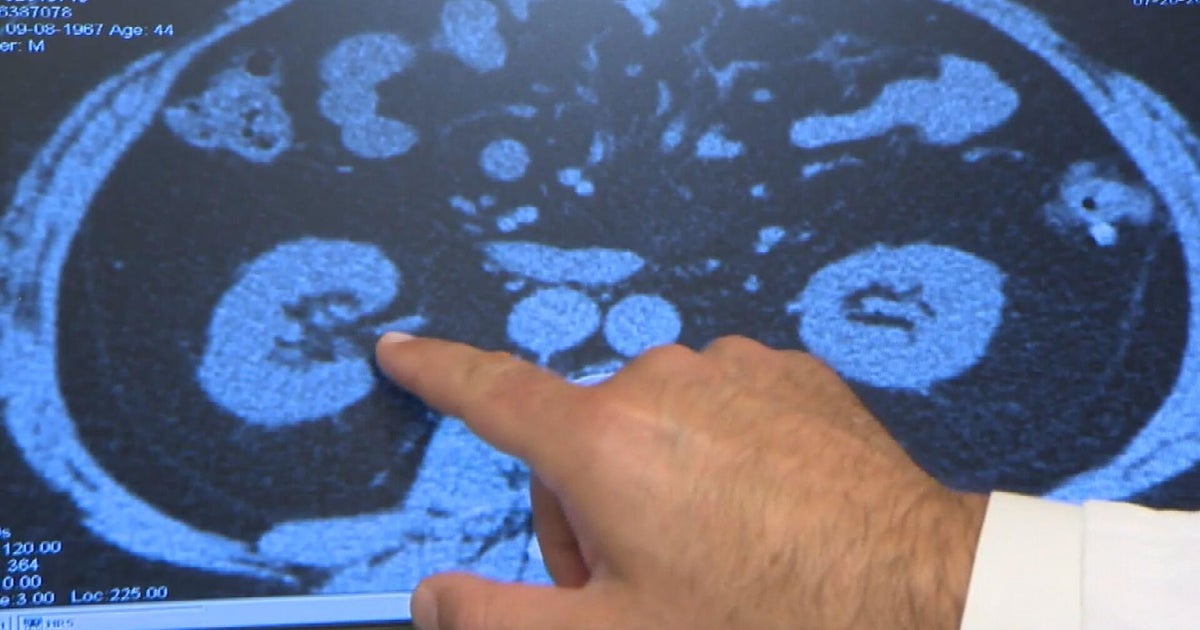

They were given six months of treatment with an immunotherapy drug called dostarlimab, from the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline, which helped fund the research. The cancer vanished in every single one of them — undetectable by physical exam, endoscopy, PET scans or MRI scans, the researchers said.

The drug costs about $11,000 per dose, The Times reports. It was administered to each patient every three weeks for six months, and it works by exposing cancer cells so the immune system can identify and destroy them.

"This new treatment is a type of immunotherapy, a treatment that blocks the 'don't eat me' signal on cancer cells enabling the immune system to eliminate them," CBS News medical contributor Dr. David Agus explains.

"The treatment targets a subtype of rectal cancer that has the DNA repair system not working. When this system isn't working there are more errors in proteins and the immune system recognizes these and kills the cancer cells."

After six months or more of follow-up, the patients continued to show no signs of cancer — without the need for the standard treatments of surgery, radiation and chemotherapy — and the cancer has not returned in any of the patients, who have now been cancer-free for a range of six to 25 months after the trial ended.

"Amazing to have every patient in a clinical trial respond to a drug, almost unheard of," Agus said, adding that it "speaks to the role of personalized medicine — that is identifying a subtype of cancer for a particular treatment, rather than treating all cancers the same."

Another surprise from the study was that none of the patients suffered serious side effects.

"Surgery and radiation have permanent effects on fertility, sexual health, bowel and bladder function," Dr. Andrea Cercek, a medical oncologist and principal investigator in the study, said in an MSK news release. "The implications for quality of life are substantial, especially in those where standard treatment would impact childbearing potential. As the incidence of rectal cancer is rising in young adults, this approach can have a major impact."

"It's incredibly rewarding," Cercek said, "to get these happy tears and happy emails from the patients in this study who finish treatment and realize, 'Oh my God, I get to keep all my normal body functions that I feared I might lose to radiation or surgery.'"

Researchers agree the trial needs to now be replicated in a much bigger study, and noted that the small study focused only on patients who had a rare genetic signature in their tumors. But they say that seeing complete remission in 100% of patients tested is a very promising early signal.

Dr. Hanna K. Sanoff of the University of North Carolina's Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, who was not involved in the study, said it is not yet clear if the patients are cured.

"Very little is known about the duration of time needed to find out whether a clinical complete response to dostarlimab equates to cure," Dr. Sanoff wrote in an editorial accompanying the paper.

But she noted, "These results are cause for great optimism."

The trial is expected to include about 30 patients, which will give a fuller picture of how safe and effective dostarlimab is in this group.

"While longer follow-up is needed to assess response duration, this is practice-changing for patients with MMRd locally advanced rectal cancer," said study co-leader Dr. Luis Diaz Jr., head of the division of solid tumor oncology at MSK.