Recovering service members lost 70 years in an Alaskan glacier

There are no white crosses amid the blue of Colony Glacier in Alaska, even though it's been the resting place for 52 U.S. servicemen, locked in frozen limbo there since 1952. It was just five days before Thanksgiving when a massive C-124 Globemaster on its way to Elmendorf Air Force Base in Anchorage lost radio contact during a storm.

On board: Eight Army soldiers, a Marine Corps major, a Navy commander, and 41 airmen, including Isaac Anderson, who left a letter to his wife behind. He'd written it two hours before he got onto the plane, said his granddaughter, Tonja Anderson-Dell.

"All I want you to do is to write me every day, and to stay sweet, and be good, and take care of my son," Anderson wrote.

His son would, tragically, never know his father. The wreckage of Anderson's plane was finally found after the storm subsided. According to a report detailing the investigation, most of the debris was buried under snow "as deep as several hundred feet … Any attempt to locate the passengers aboard will be an extremely difficult operation."

And so, the plane and its occupants were left buried in the snow and ice.

"I just couldn't understand," Anderson-Dell told correspondent Lee Cowan. "We all stand by 'We never leave our fallen behind.' With the technology we have today, you found the Titanic. You telling me that we can't find a C-124 military plane?"

Although the crash happened during the Korean War, she said the military didn't consider it a combat loss, which she believes is why it was forgotten so quickly. "Why? When they put their hand up, they're no different than the one who put his hand up and went missing in action. They're all the same. Treat us the same."

She spent years writing letters to the military, documenting other planes lost in non-combat situations, to no avail.

But in 2012 came a break: The Alaska Army National Guard, flying a training mission, spotted something in the spring melt on the glacier. It was as if the plane was reaching through the ice to be freed.

Anderson-Dell recalled, "Oh, how I danced, jumped up and down. I called my dad, crying on the phone. I'm like, 'You won't believe it. They found your dad's plane!' And he's like, 'No, they didn't. No, they didn't. It's somebody else.'"

"He just didn't believe it?" Cowan asked.

"'His luck wasn't that good,' is what he said."

But his luck was that good, and that meant it might be good for all family members left behind, like Marsha Jahn, the niece of Capt. Jerome Goebel. "I thought, 'Oh, finally we'll have some closure here,'" she said.

Jahn was only seven at the time of the crash. Goebel's nephew, Mick Mayer, wasn't even born. "When they found it, where here I have all these stories that I've heard and read, and now it's not just a story. Now it's real," he said.

Every year since 2012 a multi-disciplinary team based in Anchorage has been engaged in what is perhaps the longest-running recovery effort in the history of the U.S. Air Force. They come with buckets and patience, during a brief weather window that the spring allows.

At first glance, you wonder how they can find anything. One searcher picking through rocks said, "A lot of times, it won't just jump out at you, until it does. It's hard to explain."

The constant churning of the glacier reveals new items ever year, like aircraft parts, while it conceals others.

In the storage room at the Air Mobility Command Museum, in Dover, Del., what the ice has turned up is being preserved – shoes, caps, shaving brushes and more, like one passenger's camera.

"History is about people, and it's about their stories," said the museum's deputy director Eric Czerwinski. "It's a memory of them."

As personal as they all are, none of these items could be traced to a specific service member.

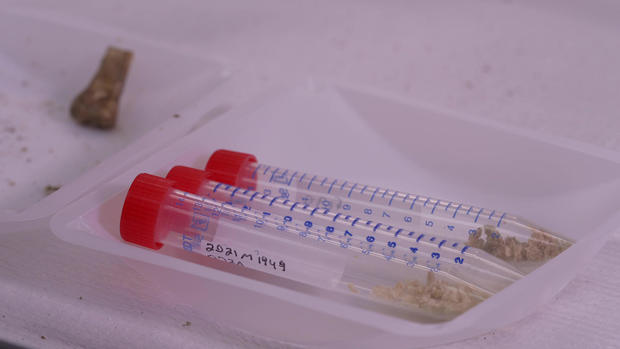

Only DNA can provide a scientific ID, and finding those precious fragments is part of the job of U.S. Air Force Captain Lyndi Minott. She uses metal forceps: "Metal scraping rock is a different sound than metal scraping bone," she said.

The remains – bones sometimes as small as a fingernail – are flown to the Armed Forces Medical Examiner at Dover Air Force Base, in Delaware, for identification.

Cowan said, "It strikes me that some of the methods you're using now to identify these servicemen wouldn't have been around in the '50s."

"Absolutely," said director Dr. Tim McMahon. "This occurred in 1952. 1953 is when Watson and Crick defined DNA."

But the technology has come far enough, that less than a gram is now needed for a positive match, which can be hugely comforting to the families.

McMahon said, "We developed methods to preserve parts of the bone, because we don't know how much of each person we may recover. So, if that's the only piece of that missing service member, the family gets something back."

The last decade of searching has paid off; 45 of the 52 service members aboard that C-124 have been identified. That includes Airman Isaac Anderson, who was finally identified from a single tooth.

Tonja Anderson-Dell said, "My father, he was just in awe, because he watched his father come home after being missing for over 60 years."

Cowan noticed around Anderson-Dell's neck two dogtags, her grandfather's – both found in the ice as well. "This was the last thing that was on my grandfather's neck," she said. "So, to have these, it makes every phone call, every letter, it makes it worth every hour."

But for Marsha Jahn and Mick Mayer, the search for Capt. Jerome Goebel goes on. He's one of the seven still locked somewhere in the ice. Jahn said, "When they said that they had found more remains, I was so hopeful this year. It would be nice to have something just to know that he didn't just vanish."

The task force says that as long as remains and artifacts are still being found, and as long as it's safe, the mission on Colony Glacier will continue until all 52 are lost no more.

Captain Minott said, "Being able to find items that we're able to link or trace back to family members, and provide that type of closure, is honestly the best feeling in the world."

For more info:

- Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage

- Air Mobility Command Museum, Dover, Del.

- Armed Forces Medical Examiner System (AFMES)

Story produced by John Goodwin. Editor: Ed Givnish.