Reconstructing Notre Dame Cathedral

It's at the heart of Paris in every sense of the word. But this landmark – which has endured since the 12th century – is now almost unrecognizable inside, as correspondent Seth Doane saw when "Sunday Morning" was granted rare access.

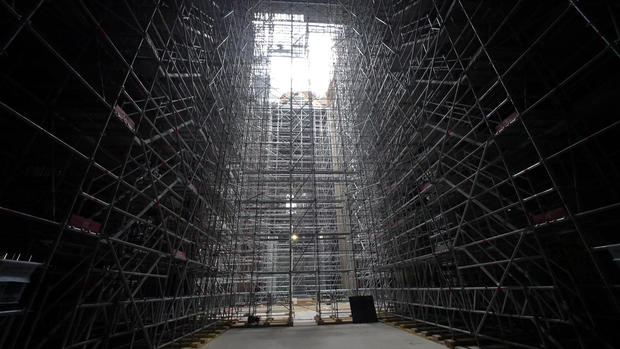

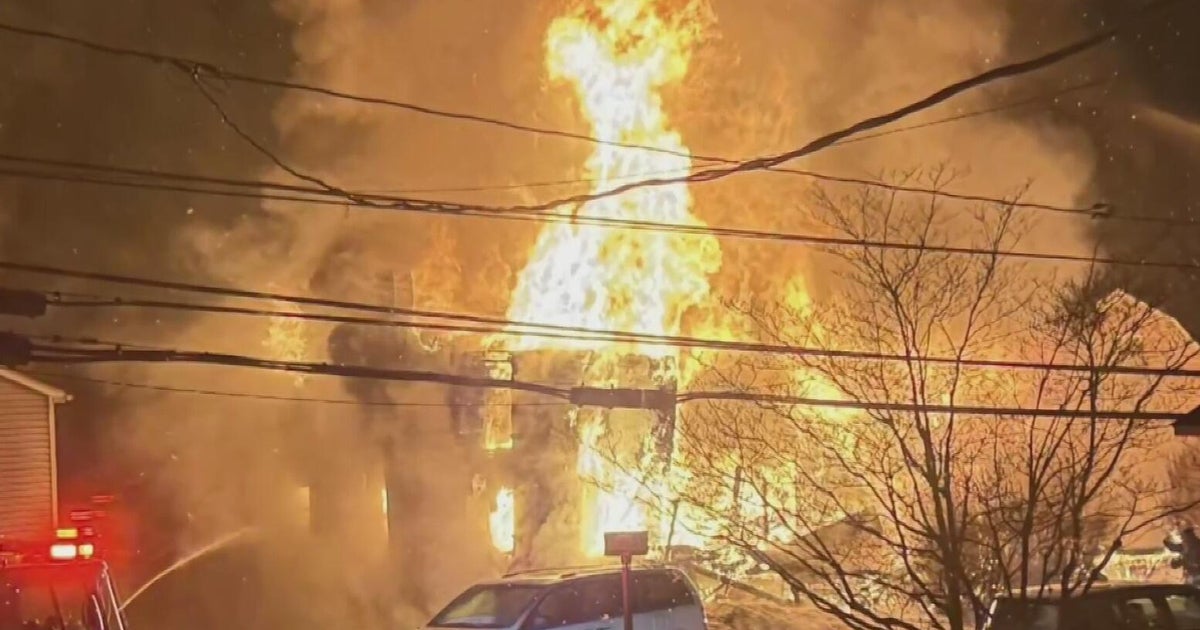

Today, Notre Dame is a cathedral of scaffolding, after that April 2019 fire (likely sparked by an electrical short) which engulfed the church.

The magnificent, 160-year-old Gothic spire toppled, and much of the roof collapsed. Remarkably, though, most of the main stone structure remained. French President Emmanuel Macron vowed to rebuild within five years.

Lead contamination from the destroyed roof and spire is just one of the many challenges slowing renovation work, and even access to the monument, as Doane found out. Those who enter are given completely new clothes, that will be disposed of afterwards.

Doane suited up this past summer to go high on the scaffolding over the cathedral to meet on this commanding perch the man in charge of the renewal effort: Jean-Louis Georgelin, who does not exactly have much time to enjoy the vistas of Paris. "Yes, it's one of the most magnificent view you can have from Paris, but only for a small time, because this will be here only for five years," he said.

He's referring to this scaffolding … and that ambitious renovation deadline.

"I'm here – me – to win this battle," he said. "It's a battle. It's a daily battle."

In fact, he's a former military general – and Georgelin said that's part of the reason Macron chose him. He's charged with managing this rebuilding effort for which they've already raised one billion dollars.

Georgelin showed Doane the gaping hole at the church's transept ("This is the heart of the drama here"), and pointed out where there once was the roof ("Here you will have in wood the framework, and above the framework, the roof in lead").

This is where a lattice of centuries-old wooden beams – known as "the forest" – made up a sort of "attic" for the church.

Doane said, "It doesn't look like it'll be ready by 2024."

"Why do you say that?" asked Georgelin. "Because you have a lot of scaffold?"

"Yes."

"But we have a plan which is very precise. Now you have what we call the stabilization to proceed to the restoration. So, in some way, the most difficult [work] has been done."

To see the work, chief architect Philippe Villeneuve took Doane into that web of scaffolding, which had initially obscured the cathedral's soaring ceiling.

Villenueve said this renovation is, for him, a "duty" and a "mission," adding: "My job is that every morning I wake up to save the cathedral."

They were putting in place temporary, custom-built wooden braces designed to support the flying buttresses.

With such a beloved landmark, there has been debate over every detail: chairs versus pews; lighting; and art. But Villeneuve told us the structure will be as close to the original as possible:

"We'll be using the exact same materials as they did during the Middle Ages and in the 19th century," he said. "We went to look in quarries to see if the stones we had were the correct density. [And for the wood], it was oak, it shall be oak. The rebuilding techniques are absolutely identical."

CBS News visited one of the French forests where they were selecting some of the 1,000 oak trees – at least a century old – for the spire and transept. Earlier this month, they began sawing the first few trees.

Notre Dame did not have modern safety equipment, like sprinklers, to slow the blaze. But French firefighters had trained to fight a fire at the cathedral. They used water at lower pressure and tried to avoid directly spraying the hot stained glass. Villenueve said the treasured stained-glass windows, which he called are irreplaceable, were spared.

There are carpenters, stone masons and iron workers – artisans from about 20 different specialties – at work here, some in this medieval place using this most modern of implements, including a drone fitted with special imaging technology.

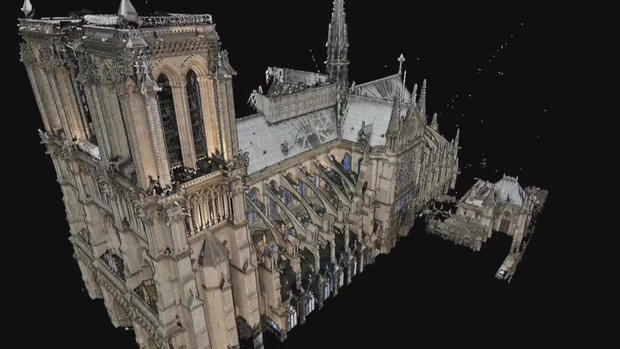

Philippe Dillman is research director at France's National Centre for Scientific Research (the CNRS). He showed us what he calls Notre Dame's "digital twin" – high resolution images in his computer. "We made 3-D maps to understand the way they were built, and the way ancient people built these cathedrals, but also to restore them," he said.

And they can compare these images with high-resolution ones taken before the fire. They've examined how the monument moved where it was stressed by the fire and the temperatures at which it burned. They're trying to understand where specific pieces were placed.

Some materials, like stone, can be re-used. But not burned wood.

Doane asked, "So, why does it matter if you know where, exactly, that [piece] came from, if you can't put it back?"

"It's a matter of knowledge of the ancient carpentry," Dillman replied.

And in trying to understand those processes, there have been some unexpected revelations from materials like that centuries-old wood:

"We can have indications on the medieval climate, the evolution of the medieval climate, just by looking on the isotopes inside the wood," Dillman said.

"Wow, so you're not only learning about putting the cathedral back together, you're also learning bits and pieces of history, climate?' asked Doane.

"Exactly – sciences for the rebuilding of the cathedrals, but it's also the cathedral's for science."

They're tantalizing details. This precious time capsule is inspiring and challenging artisans of our modern era – charged with preserving the majesty of the past.

For more info:

Story produced by Elaine Cobbe and Robbyn McFadden. Editor: Emanuel Secci.