Raw sewage and toxins have been polluting our waterways for decades: "Most people don't know about it"

The significant amount of pavement covering the modern world is creating an environmental problem — every time it rains.

In many places where rain cannot be absorbed into the ground where it falls, it runs off the pavement and into nearby waterways. The runoff carries pollutants like fertilizer oil, pesticides and bacteria.

It may also force raw sewage to spill into the water.

"CBS This Morning" co-host Tony Dokoupil spoke to people working to fix the problem.

"This is a magnificent, majestic river," environmentalist John Lipscomb told Dokoupil on a windy day out on the Hudson River.

As a member of the group RiverKeeper, Lipscomb has been patrolling the Hudson for decades, marveling as salt water from the ocean flows up — but also worrying about what is flowing in every time it rains.

"Bottle caps, cigarette butts, you name it," he said, adding that the debris was a "visual indicator of what the stormwater has carried off the streets into the river."

But according to Columbia University researcher Elise Myers, it's what cannot be seen that is the bigger concern.

"When we have a lot of these areas where the water just runs straight off, it can carry whatever's on here," Myers said. "So trash, but also chemicals and things like that. And in urban areas where you have that high concentration, definitely something to be worried about."

The Environmental Protection Agency calls polluted runoff "one of the greatest threats to clean water."

Standing in the marsh along the Hudson, north of New York City, Myers said that marshes are "really critical to ecosystems."

"Here I'm seeing a lot of bacteria that usually we only find inside the guts of warm-blooded animals like ourselves. And so when we find them in the water it's an indication that we have some sort of sewage contamination," she said.

Unfortunately, Myers said, "there's definitely a way that something you have flushed down — some of those bacteria can end up out here."

She explained that rain can overwhelm sewage treatment plants, and in nearly 800 cities across the country, raw sewage overflows into the water by design in a downpour.

Those cities have what is known as "combined sewer systems," where what goes down the drain at home mixes with what washes off the streets outside.

When it rains, those systems can release a mix of sewage and polluted stormwater instead of backing up into residents' homes.

As Dokoupil traveled back down into New York City, John Lipscomb of RiverKeeper showed him some of the hundreds of points in that area alone where sewage enters water.

"City has said this is what we must do, because we can't do better. And the state okays it. Those are state permits," he said. "And the EPA knows it. And the EPA is, of course, the federal agency that oversees all the states."

Asked why this open information has not caused a scandal, Lipscomb simply answered: "Most people don't know about it."

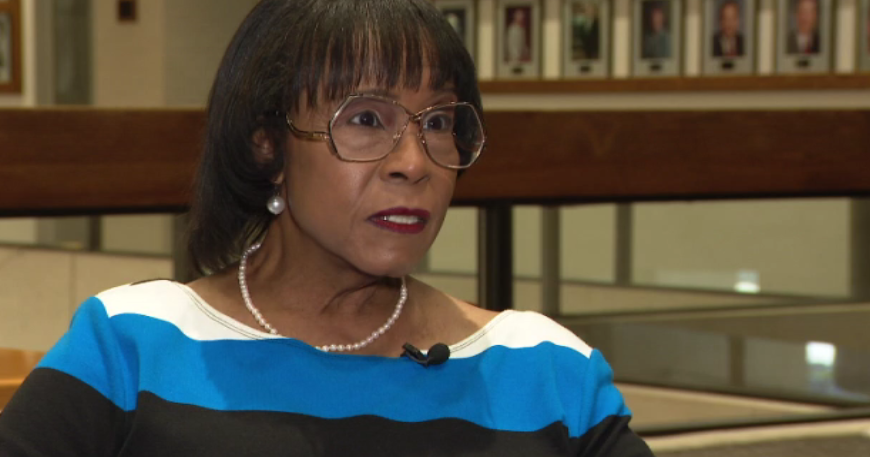

Yet it is something the New York City Department of Environmental Protection is working to address, according to Deputy Commissioner Angela Licata.

She revealed how the city is trying to keep water out of the system with surfaces that can absorb more of it into the ground.

"This synthetic turf here is designed to hold about a million gallons of stormwater a year," she said.

Dokoupil asked, "So without these changes, all that would have run over the regular old road and ended up in the drain?"

"Exactly," Licata replied.

The city is also redirecting stormwater into thousands of tiny new "rain gardens" designed to soak up runoff. The local government has built massive tanks that can hold tens of millions of gallons of sewage that would otherwise spill into the water, spending billions of dollars on these projects.

There have been some results. According to data from the New York Department of Environmental Conservation and the NYC Department of Environmental Protection, the amount of combined sewage overflow has dropped 26% since 2008, and more than 80% since the 1980s.

"There's been a tremendous improvement. Now it's finishing the job," Lipscomb said.

The Hudson is now clean enough for many locals to get out and enjoy it — but even if it doesn't make you sick, finding out that 20 billion gallons of sewage still gets released into it every year could make anyone think twice.

So as environmental leaders figure out how to stop toxins from entering the water, people like environmentalist Robina Taliaferrow are working on a way to clean up what's already there.

"So we're heading over to our oyster reef cabinets," she told CBS News. "What they do is they help clear the water."

Taliaferrow is part of the Billion Oyster Project, installing oyster reefs in New York Harbor.

A single adult oyster can filter 50 gallons of water every day.

"They will pull out of the water those particles, those things," Taliaferrow explained, "They will pull that… and actually create like a casing and drop it to the bottom of the water column."

She said they help to a "certain degree" — but John Lipscomb says a complete fix will require more money, and more pressure from the public.

"We've got a vehicle driving around on Mars right now," he said. "And we've walked on the moon. Don't tell me this can't be done."