Breaking through Russia's digital Iron Curtain

In the fight against disinformation, this is the front line: The Prague studios of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, where writers, producers, and social media hosts are battling Kremlin propaganda.

"Our role is to provide surrogate journalism, essentially local journalism, in countries where freedom of the press is under assault," said Jamie Fly, the president of RFE, which operates in 27 languages and 23 countries, including Russia. "These are countries where the message is decided every day in a government office about what people should see, what they should hear, what they should be told."

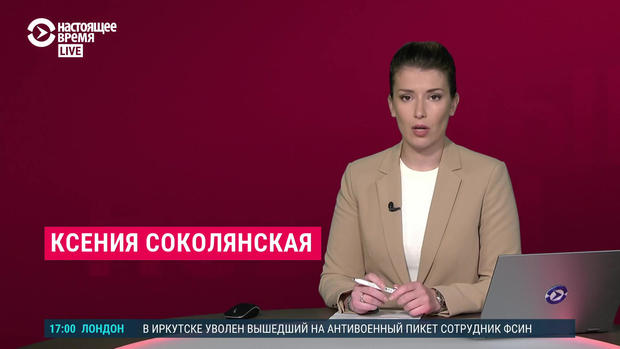

Correspondent Christina Ruffini asked Ksenia Sokolyanskaya, an anchor for RFE's Russian-language network, "What is it like covering this conflict as a Russian?"

"There is no easy way to talk about it," Sokolyanskaya replied. "I don't want to push anyone. I think that people should come to conclusions themselves. [But] they need to have the options. And that's the biggest problem with media in Russia: there are no other options."

Those other options disappeared earlier this month when Russian President Vladimir Putin imposed a restrictive new media law, forcing almost all independent outlets to shut down.

Fly said, "We were warned that unless we started to censor our content about the war in Ukraine, that we would be blocked. We refused to censor, and so, our websites are now blocked inside Russia."

- What Russians can see of their war against Ukraine ("Sunday Morning")

- The social media war between Ukraine and Russia ("Sunday Morning")

- Russia blocks Facebook and Twitter access

And that's where Patrick Boehler comes in. He's the head of digital strategies, helping keep RFE and its consumers one step ahead of the censors. "Part of it's a cat-and-mouse game, where you try to anticipate what they're going to do, and you react," Boehler said.

"So, is it kind of a race against time to stay ahead of whatever measure they're implementing?" asked Ruffini.

"They will block our site, then they might block a copy of our site. But then we just create another copy of our site. And then another copy, another copy …"

"So, it's whack-a-mole?"

"That's right, yeah."

The strategy seems to be working: since the war began, RFE says its page views from inside Russia are up 51%.

Getting past Russian censors is familiar territory to RFE. It started in the 1950s as a Cold War counter-propaganda machine piercing the Iron Curtain with short-wave radio broadcasts. It claimed to be entirely funded by public donations, but that wasn't true, as CBS' Mike Wallace reported in 1967: "If you responded to the many appeals for Radio Free Europe, then you became part of a CIA cover."

CIA involvement ended in 1971, and RFE became an independent agency openly funded by Congress.

Still, since the fall of the Soviet Union, the organization has seen its relevance questioned and its funding slashed – even as Moscow has re-tooled its messaging machine for the digital age.

Fly said, "It is harder to reach audiences now. State propaganda today is much more sophisticated. We have to compete more, and have to be more relevant and nimble than we did during the Cold War to adapt to audience trends."

Far from a Cold War relic, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty says its mission is now more relevant than ever. Earlier this month Congress increased RFE's budget 15 percent.

"Information, honest, truthful, objective reporting will play a huge role eventually in helping bring about change inside Russia," said Fly.

"You think, ultimately, truth will win out?" asked Ruffini.

"Everyone in this building subscribes to that notion," Fly replied. "Otherwise, they wouldn't be working for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty."

For more info:

Story produced by T. Sean Herbert and Dustin Stephens. Editor: Chad Cardin.