What does Qatar get out of the prisoner swap?

LONDON -- Qatar, a tiny nation in the Persian Gulf, played a key role in negotiating the prisoner swap between the Taliban and the United States to free Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl.

U.S. policy doesn't allow for direct negotiation with terrorists, but as CBS News correspondent Margaret Brennan explains, President Obama was able to bypass that by having U.S. diplomats deal instead with Qatar as a third party.

It was a role that no other country could have played, and the ability to act as a bridge between the West and the world of radical Islam makes Qatar a vital player in geopolitics, and could serve as an insurance policy to a royal family which has ruled without serious challenge for about a century and a half, in a region where upheaval has become the theme of the day.

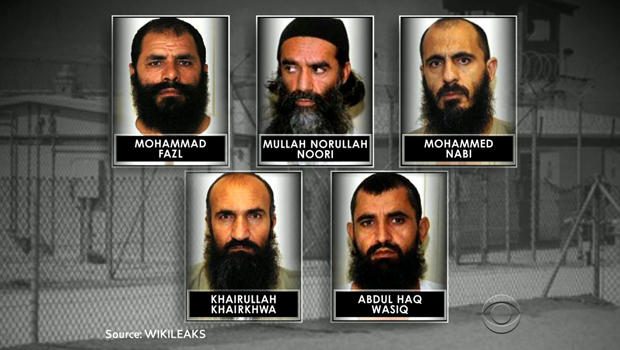

The five senior Taliban figures who walked out of the U.S. prison camp in Guantanamo Bay join a cadre of other Muslim militants living in exile in Doha. Senior members of the Muslim Brotherhood fled to the Qatari capital when their government -- which rose to power on the wave of the Arab Spring -- was toppled in Egypt.

Qatari Emir Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani was handed all the power in his country by his father in June 2013, as the fallout from the Arab Spring-inspired uprisings in Egypt, Syria and Libya was still becoming clear.

Even before the young Emir got his job, his family had decided to throw its weight behind (and by many accounts, it continues to fund) some of the hardline Islamic groups fighting in Syria, and Libya. Qatar still has strong ties to the Muslim Brotherhood.

Last year, the Taliban opened a diplomatic mission in Qatar, though it was officially closed about a month later in the face of widespread criticism from Kabul and the U.S. over the extent to which the office was portrayed as a government-in-exile.

Regardless of its official status that office in Doha remains open, and a group of Taliban officials still live and work in Qatar. A video released by the militant group on Sunday shows the newly-freed members being welcomed into Qatar -- oddly by the side of a dusty road after they pull up in a convoy of SUVs -- by the local Taliban contingent. More than a dozen Afghan Taliban members were on hand for the momentous occasion, along with a few Qatari officials.

At the same time, Qatar hosts one of the most important U.S. military bases in the world, at the al Udeid Air Base. The Qataris enjoy cordial relations with Israel, which has a trade mission in Doha. And on the opposite side of the Muslim world's religious spectrum from the Taliban and the Muslim Brotherhood, Qatar also maintains ties with the Shiite Muslim regime in Iran.

"Qatar likes to punch above its weight class and influence internationally with its significant resources, control of al Jazeera, and ability to manage varied and often conflicting diplomatic relationships at the same time," said CBS News' senior national security analyst Juan Zarate.

Trying to keep all sides happy is no easy chore, however, and Qatar's decision to back Islamist groups, it's use of al Jazeera to try and effect events in other countries -- particularly in Egypt -- and the eagerness displayed by Doha to put itself at the center of regional disputes, has put it at odds with its much larger neighbor Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states.

Saudi's own royal family has weathered the Arab Spring in-tact, but those leaders and their counterparts in Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates have taken the sudden (if ephemeral) rise of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, and the still roiling chaos in Libya and Syria, as a warning.

Last month, Saudi, the UAE and Bahrain withdrew their ambassadors to Doha as a clear sign that Qatar was trying tempers.

As CBS News consultant Jere Van Dyk explains, Qatar is an enormously wealthy, authoritarian "island sitting on a pool of natural gas... and thus is insecure in a sea of Arab poverty, chaos and yearning."

In other words, even though Qatar remains peaceful and there has been no uprising there, just like its Sunni Muslim neighbors, Qatar's Sunni royal family is worried about the rise of Shiite Iran, and worried about a destabilizing spillover of violence from Syria and Iraq.

Unlike its neighbors, however, Doha has tried to walk a delicate line and keep the Islamists, the West, and its Arab neighbors happy -- or at least on talking terms.

"Deep down, they are all afraid of the Islamists," says Van Dyk. But while Saudi Arabia works with the Egyptian military and other regional powers to try and destroy them, "Qatar has essentially sought to buy them off."

It was a strategic decision likely made several years ago, when the Brotherhood seemed poised to control Egypt, and when the heavily-Islamist Syrian rebel factions were still gaining ground against the Assad regime.

All of that calculus has changed dramatically within the last year, but so far -- as Doha's ability to facilitate the U.S.-Taliban prison swap shows -- Qatar has managed to play all sides and create a unique role for itself in Middle East politics. That can't hurt the royal family's prospects for self-preservation.