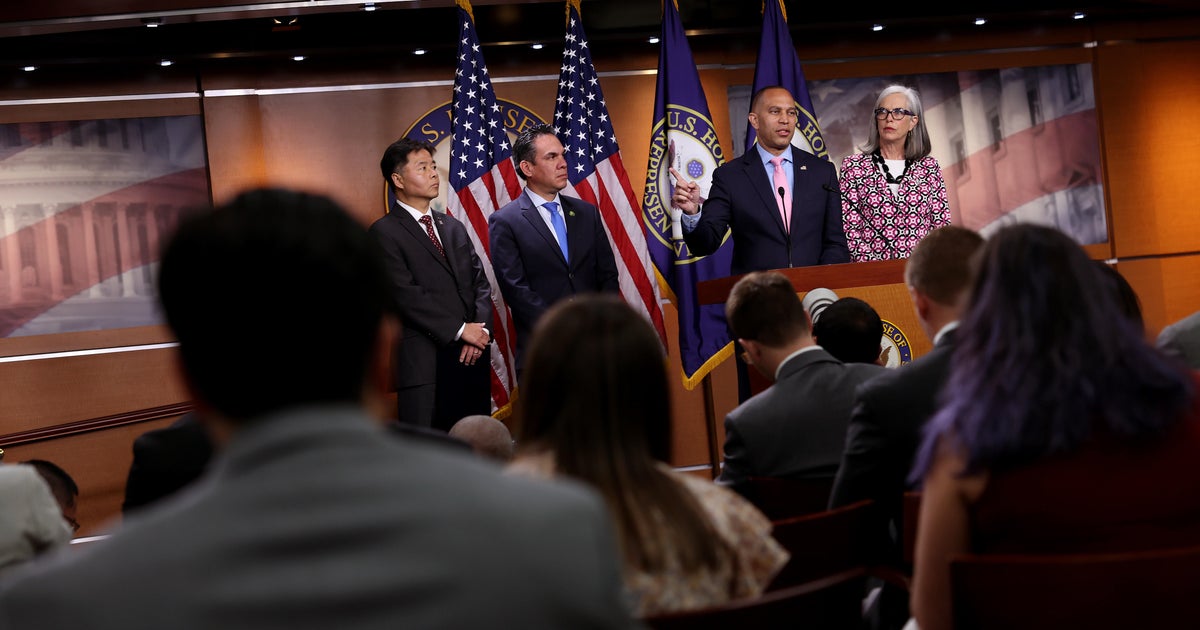

Once challenged by House Republicans, proxy voting becomes tool for both parties

Washington — On a Tuesday afternoon in early February, Rep. Ro Khanna, a Democrat from California, participated in an event with the Philadelphia Inquirer from the inside of a vehicle parked outside the U.S. Capitol.

But at the same time, his colleagues were in the House chamber, casting votes on a bill to name a post office in Slatersville, Rhode Island. A review of the roll call vote shows Khanna supported designating the facility as the "Specialist Matthew R. Turcotte Post Office," even though he was not physically present to vote "yea."

Instead, he enlisted Rep. Jimmy Gomez, a fellow Democrat from California, to vote for him, citing in a letter to the House clerk the "ongoing public health emergency" as his reason for being unable to participate in the proceedings in-person.

Weeks earlier, New York Rep. Elise Stefanik, the No. 3 House Republican, cast two votes in the House on the afternoon of Jan. 11, but posted photos to Twitter that night showing her alongside former President Donald Trump at his South Florida estate, Mar-a-Lago, where she attended an event with the 45th president.

Like Khanna, Stefanik said in a letter to the House clerk she was unable to physically attend the proceedings "due to the ongoing public health emergency," and tapped GOP Rep. Dan Meuser of Pennsylvania to vote in her stead.

The instances involving Khanna and Stefanik are just two examples of House members using proxy voting to do their day jobs in Washington without actually being in the Capitol.

Congress is approaching the two-year anniversary of approving a resolution that allowed House members to vote remotely by designating another lawmaker as their proxy. Implemented to keep the wheels of government turning during the COVID-19 pandemic without requiring all 435 House members to gather on the floor together, the practice was initially maligned by GOP members — so much so they sued to stop it — but has come to be embraced by Democrats and Republicans alike.

"We accommodate to the necessities that confront us in life, and proxy voting and virtual work is accommodating to issues that we confront in life," House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, a Maryland Democrat, told CBS News.

While proxy voting began as a mechanism for lawmakers to remain safe during the pandemic without missing votes, reasons for the remote participation have morphed over the span of the pandemic from concerns about the public health emergency to overt participation in political activities.

In late February 2021, for example, nearly a dozen GOP lawmakers authorized colleagues to cast votes for them, citing the "ongoing public health emergency," only to appear at the Conservative Political Action Conference in Orlando, Florida.

Four months later, in June, a group of Republicans appeared alongside Trump in South Texas for a visit to the U.S.-Mexico border while still voting in Washington by proxy.

Democrats, meanwhile, have taken advantage of the absentee voting policies to appear alongside President Biden in their home states, while simultaneously fulfilling their voting obligations in Washington.

When Mr. Biden visited Michigan in May, for example, he was greeted at the airport in Detroit by Reps. Debbie Dingell and Rashida Tlaib, and by other Democrats in the Michigan delegation at the Ford Rouge Electric Vehicle Center in Dearborn. All had voted by proxy, according to letters submitted to the House clerk.

And Rep. Kai Kahele, a Democrat from Hawaii, recently came under scrutiny for his extensive use of proxy voting, employing the practice for 120 of the 125 roll call votes so far this year. His office, though, defended his record of voting-by-proxy, saying in a statement that staff has tried to reduce his cross-country travel to limit his exposure to COVID-19 "while ensuring he fulfills all of his responsibilities in Congress."

Three Democrats have not voted in person at all this year, voting records show.

"Members miss votes, that's a fact of the House," Molly Reynolds, a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution who analyzed the use of proxy voting. "Now we have this situation where instead of having to choose between missing a vote and not doing something else, they can do the other thing and use proxy voting."

Reynolds found there are several categories of reasons members vote-by-proxy: Some lawmakers choose to engage in political activities, while others find themselves in circumstances where they need workplace accommodations, such as when GOP Rep. Dan Crenshaw of Texas used proxy voting after undergoing emergency eye surgery last year that restricted his ability to travel.

And while there are few questions as to what constitutes an abuse of the pandemic-related voting procedures, other uses by lawmakers — Democratic Rep. Colin Allred of Texas voted by proxy while on leave after the birth of his son — make it difficult for congressional leaders to draw clear lines of what is permissible and have exposed flaws in Capitol Hill as a workplace.

"As we consider the future of proxy voting — when we no longer live in a world where there are acute COVID concerns or get to a point where COVID isn't as acute of a concern — Congress would certainly not want a system that continues to let people vote while going to political fundraiser, but the House might want a way to let members participate remotely for a defined reason for short period of time," Reynolds said. "And figuring out what it looks like is hard for a legislative body, particularly in the current political environment."

Rep. Jackie Speier, a Democrat from California, said she believes the ability for lawmakers to take family leave should be written into House rules.

"Life happens," Speier told CBS News, adding "if you extend remote voting for extreme circumstances, emergency circumstances, I think that serves the House well, it serves the individual members well, and it's part of being in the 21st century."

She noted, though, there are clear differences in the reasons for voting by proxy that should be allowed.

"It's one thing to use it when you have a family emergency or you're giving birth or a family member's died," Speier said. "It's another thing to use it to go to a political event."

A contested policy, eventually embraced

Since the House first passed the resolution authorizing proxy voting in May 2020, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has extended the procedure several times, most recently through mid-May.

GOP lawmakers at first lambasted the use of proxy voting, and 160 members of the House Republican conference signed on to a lawsuit brought in federal court challenging the absentee voting procedures. In fact, until December 2020, no GOP lawmaker voted by proxy, according to the analysis conducted by the Brookings Institution.

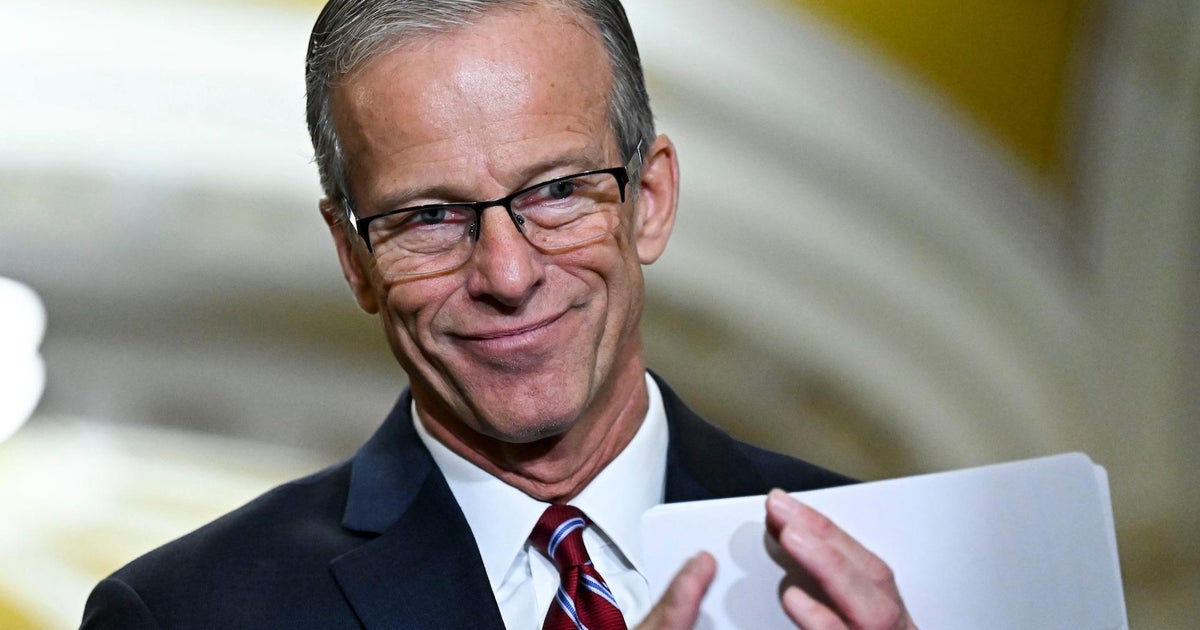

But as the COVID-19 pandemic continued, now in its third year, many of those same Republicans have taken advantage of the ability to cast votes in Washington without actually being physically in the House chamber. And as the suit against Pelosi spearheaded by Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy weaved through the federal judiciary last year, the number of GOP lawmakers listed as plaintiffs waned.

By the time the dispute landed before the Supreme Court in September, only McCarthy and Texas Republican Congressman Chip Roy remained as plaintiffs. The high court ultimately rejected the GOP lawmakers' appeal of a lower court decision tossing out the case, leaving the proxy-voting process in place.

An analysis of the practice conducted by the Ripon Society, a center-right think tank, found that of the proxy votes cast during the first session of the 117th Congress, across 2021, 72% were cast by Democrats, while 27% were from Republicans.

Of the 225 Democratic House members, 202 voted by proxy, while 137 of the 215 Republicans used the procedure last year. Just 65 lawmakers did not engage in proxy voting at all, neither serving as a proxy nor tapping another member to vote for them, the Ripon Society found.

The Brookings analysis published in January found the typical GOP lawmaker had an open proxy letter for an average of 13 days as of mid-December, while the typical Democrat has had an open proxy letter for an average of 19 days.

Even as Republicans continue to make use of their ability to cast proxy votes, GOP leaders have pledged to do away with the practice, should the party retake the majority after the November midterm elections.

"Our very first day is rules, OK? We're no longer going to do proxy voting," McCarthy previewed to reporters of Republicans' first action at the start of the next Congress if they regain power.

Reynolds, of Brookings, agreed there are some pitfalls of proxy voting, including that members are not physically present on the House floor to speak, offer amendments or make motions.

"In lots of situations, the process in the House is locked down, but if we aspire to a more deliberative House floor, that'll be incompatible with widespread proxy voting," she said.

But there are less direct consequences, such as members losing the direct engagement with one another.

"If you've watched the House floor during a regular vote, there are important conversations that happen in person, and not just whipping votes, but all kinds of in-person interactions that have shaped and driven the culture of the House," Reynolds said. "It's harder for members, not impossible, to build relationships."

Hoyer agreed that being in-person for House proceedings is "the ideal, particularly for an institution that relies on the kind of give-and-take in debate that democracy flourishes under." But he noted that technology has extended the bounds of what Congress can accomplish without being physically present.

"I think that what our constituents elected us to do is to represent them. How do we do that? We vote and we speak, but we don't have to speak in this room, that room, in the other room, or vote at that machine, that machine or the other machine," he said. "We can do so virtually and with using technology and affecting the same result."