Portland's racist past smolders beneath the surface

Americans live in a world where issues of race often populate headlines: the deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, Colin Kaepernick's controversial kneeling during the national anthem, the deadly white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the rhetoric around building a wall.

In cases of tragedies, people rush to social media to communicate their shock. "How could something like that happen here?" they wonder. Then, some condemn the individual involved in an atrocity and file the event away in their minds as a sort of enigma -- a case in which a bad man entered an otherwise good city and did something unthinkable.

When you delve deep enough beneath the surface of such "otherwise good cities," however, you often find deep-rooted issues that may have contributed to an event. That's what the latest "CBSN Originals" documentary, "Portland | Race Against the Past," does with the presumed liberal enclave of Portland, Oregon, where in the spring of 2017, three men were stabbed by a white supremacist on a MAX train after coming to the defense of two minority women he was harassing.

As with similar cases across the country, Americans responded with incredulity: Portland? Many people on the ground in Portland, however, were not shocked. Quite the opposite.

Keegan Stephan, a caucasian political organizer who spent his high school years in a suburb of Portland tells CBS News: "When I first saw the news, I flashed back to my time there and some of the really violent racist comments I'd hear white people in the presence of white people make. It made perfect sense to me that that sort of violent, racist behavior was going on in Portland and that it had led to this."

Oregon historian Walidah Imarisha agrees. "I was absolutely not shocked," she said. "I didn't meet any people of color who were shocked. They were horrified. They were terrified. They were enraged. They were saddened. There were many emotions happening, but surprise was not one of them because we live in Portland every single day and we see the mask that Portland puts on for the rest of the world. And we see that it is paper thin and we have to look under it every single day."

Experts point to a few pivotal events in Oregon's history that set the scene for events that transpire today.

Oregon's Constitution

When Oregon became a state in 1859, it did not become a slave state. People often assume that it entered the Union as a free state, but that isn't the case, either. Oregon entered the Union as its sole no-blacks state -- a little-known fact that has eluded many Oregonians.

"I've met many Oregonians who are very proud that Oregon came into the Union a free state. And the reality is much more complicated," said Imarisha. "That same law that outlawed slavery also included the black exclusion law that said that black people weren't allowed to live in Oregon, and it included the Lash Law that said that black people would be publicly whipped every six months, up to 39 lashes, until they left the state."

The language remained on the books until 2002. And when the 14th and 15th Amendments were ratified across the country in the years after the Civil War, giving black men the right to vote and granting citizenship and equal protection under the law to "all persons born or naturalized in the United States," Oregon failed to ratify those amendments for nearly a century.

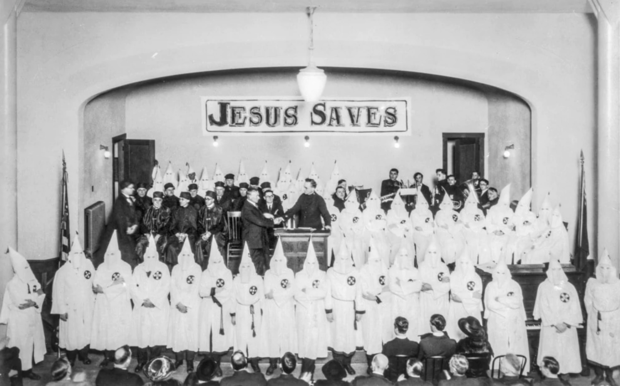

The KKK

Due in large part to the inhospitable nature of its constitution, by the 1920s, Oregon had developed the largest Klan membership per capita of any state in the Union.

"One thing that many people don't understand about Oregon is the importance of the Ku Klux Klan," said Judith Margles, executive director of the Oregon Jewish Museum. "[Oregon's] Klan in 1923 was the largest Klan west of the Mississippi. And if we think about the issues that we're facing with white supremacy today, they didn't just happen, right? The white supremacists didn't just decide in the 1990s, 'Oh, let's come to Oregon and see what havoc we can raise.' Of course, there's a direct line from white supremacists today through to the Ku Klux Klan, right back to 1844 to that first exclusion law."

The Vanport Flood

At the time of the 1940 census, black residents made up just 0.2 percent of the state's population. However, all that changed during World War II, when industrialist Henry Kaiser recruited thousands of black workers from the South to work in his shipyards, building ships for the war effort. The problem was that black people were legally only allowed to live in a small sector of Portland proper and there was not nearly enough room in that district for the thousands of workers answering Kaiser's call.

"These thousands of black folks who were coming had no place to live. The Housing Authority of Portland refused to build additional housing for these workers," said Imarisha. "So Kaiser said, 'I'm rich. I can build myself a city.' And that's exactly what he did. He built a city on unincorporated land between Vancouver, Washington and Portland, Oregon, and called it Vanport. It became the second largest city in Oregon and it was 40 percent black."

However, Vanport was never intended to be permanent, only a temporary solution to the labor needs of World War II. All of its houses were built hastily and economically, with wooden foundations rather than more substantial materials. Despite that, when the war ended, there was nowhere else for black families to move. So, they remained in a temporary city, surrounded on all sides by bodies of water, and in houses constructed with what Imarisha calls "shoddy materials." They were sitting ducks when, in the spring of 1948, after a winter of particularly heavy rainfall, a dam broke and washed the entire city away in less than an hour.

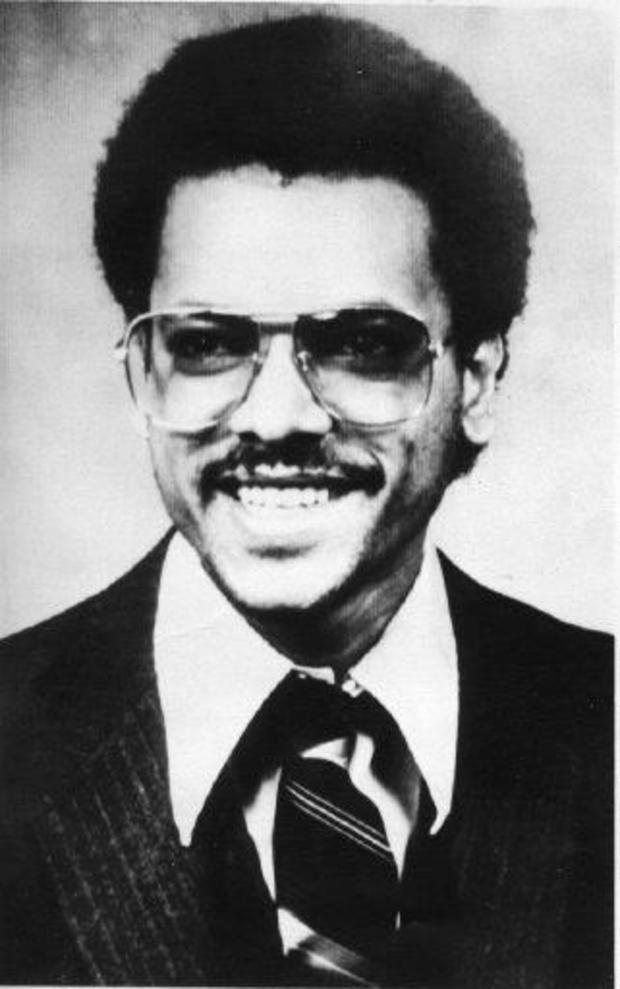

The murder of Mulugeta Seraw

By the 1980s, Portland, Oregon, had become the skinhead capital of the United States, with rival gangs of white supremacists intermingling with the city's thriving punk rock scene. And it all came to a boiling point in 1988, when three members of a local skinhead gang, called East Side White Pride, beat an Ethiopian immigrant to death with a baseball bat in the street outside his apartment building.

Much like the days and weeks after Jeremy Christian stabbed two men to death on a train in May 2017, people were shocked. Local politicians took to rallies with emphatic statements like, "Racism is un-Oregonian."

"They acted as if Oregon were not in fact an extremely racist place," recalls Elinor Langer, author of "A Hundred Little Hitlers." "Nothing could be further from the truth."

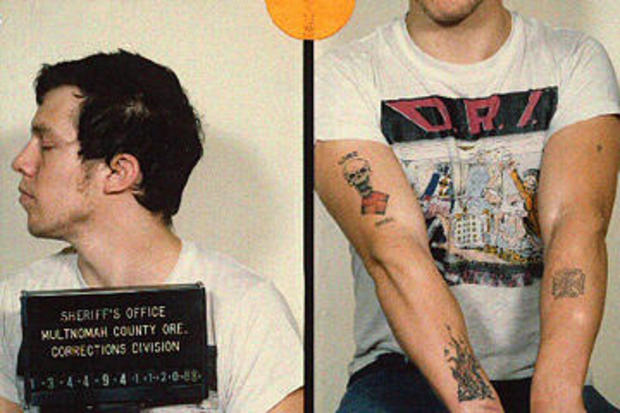

And while the three skinheads involved in Mulugeta Seraw's brutal murder were sentenced to time in prison for their crimes (life for Ken Mieske and 20 years for his cohorts, Kyle Brewster and Steve Strasser), experts say that what came next was yet another example of Portland skirting responsibility for its chronic white supremacy problem.

A lawsuit from the Southern Poverty Law Center shifted the focus to another trial, in which the city tried a California-based white supremacist leader, named Tom Metzger, for the crime. Metzger was the leader of the comparatively massive hate group, White Aryan Resistance (WAR), and the Southern Poverty Law Center saw this as an opportunity to bankrupt his organization for its role in influencing the three skinheads involved.

The Metzger trial was ultimately a victory and achieved exactly what the SPLC hoped it would, but some experts feel it allowed the city to project the blame on an outsider.

"This is what Oregon has been doing since Oregon existed as a state," said Imarisha. "Oregon can't put this on someone else."

White supremacists today

Much like the stabbing that inspired this documentary, the Portland that "CBSN Originals" showcases isn't an enigma. It is a microcosm of a much larger problem in American life today. So, while the details of Portland's racist history are unique, racist undercurrents have likely been lurking beneath the surface of other cities across the country, too. Until Americans confront that uncomfortable reality in open discussion, experts believe that nothing will change.

"This direction of these ideas or these movements from the fringes, which they were, to the center -- from the little music clubs in Portland, I mean, to essentially the White House -- that's a huge reality of American life," Langer said. "There is a movement, whether you call it white nationalism or white supremacy or neo-Nazi, and that is growing. That was exemplified by what happened in Portland and that is not secret anymore. It's not undercover."