Posting hateful speech online could lead to police raiding your home in this European country

If you've ever dared to read the comments on a social media post, you might start to wonder if civilized discourse is just a myth. Aggressive threats, lies, and harassment have unfortunately become the norm online, where anonymity has emboldened some users to push the limits of civility. In the United States, most of what anyone says, sends, or streams online — even if it's hate-filled or toxic — is protected by the First Amendment as free speech. But Germany is trying to bring some civility to the world wide web by policing it in a way most Americans could never imagine. In an effort, it says, to protect discourse, German authorities have started prosecuting online trolls. And as we saw, it often begins with a pre-dawn wake-up call from the police.

It's 6:01 on a Tuesday morning, and we were with state police as they raided this apartment in northwest Germany. Inside, six armed officers searched a suspect's home, then seized his laptop and cellphone. Prosecutors say those electronics may have been used to commit a crime. The crime? Posting a racist cartoon online. At the exact same time, across Germany, more than 50 similar raids played out. Part of what prosecutors say is a coordinated effort to curb online hate speech in Germany.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What's the typical reaction when the police show up at somebody's door and they say, "Hey, we believe you wrote this on the internet,"?

Dr. Matthäus Fink: They say-- in Germany we say, "Das wird man ja wohl noch sagen dürfen." So we are here with crimes of talking, posting on internet, and the people are surprised that this is really illegal to post these kind of words.

Sharyn Alfonsi: They don't think it was illegal?

Dr. Matthäus Fink: No. They don't think it was illegal. And they say, "No, that's my free speech." And we say, "No, you have free speech as well, but it is also has its limits."

Interpreting those limits is part of the job for Dr. Matthäus Fink, Svenja Meininghaus and Frank-Michael Laue: a few of the state prosecutors tasked with policing Germany's robust hate speech laws, online. After its darkest chapter, Germany strengthened its speech laws. As prosecutors explain it, the German constitution protects free speech but not hate speech. And here's where it gets tricky, German law prohibits any speech that could incite hatred or is deemed insulting.

Sharyn Alfonsi: It's illegal to display Nazi symbolism, a Swastika or deny the Holocaust. That's clear. Is it a crime to insult somebody in public?

Svenja Meininghaus: Yes.

Frank-Michael Laue: Yes, it is.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And it's a crime to insult them online as well?

Svenja Meininghaus: Yes.

Dr. Matthäus Fink: The fine could be even higher if you insult someone in the internet.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Why?

Dr. Matthäus Fink: Because in internet, it stays there. If we are talking face to face, you insult me, I insult you, okay. Finish. But if you're in the internet, if I insult you or a politician.

Sharyn Alfonsi: It sticks around forever.

Dr. Matthäus Fink: Yeah

The prosecutors explained German law also prohibits the spread of malicious gossip, violent threats, and fake quotes.

Sharyn Alfonsi: If somebody posts something that's not true, and then somebody else reposts it or likes it, are they committing a crime?

Svenja Meininghaus: Yeah, in the case of reposting it is a crime as well, because the reader can't distinguish whether you just invented this or just reposted it. It's the same for us.

The punishment for breaking hate speech laws can include jail time for repeat offenders. But in most cases, a judge levies a stiff fine and sometimes - keeps their devices.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How do people react when you take their phones from them?

Frank-Michael Laue: They are shocked. It's a kind of punishment if you lose your-smartphone. It's even worse than the fine you have to pay.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Because your whole life is typically on your phone now.

The application of Germany's decades-old speech laws to the online world was accelerated after an assassination, fueled by the internet, sent shockwaves through the country. In 2015, a video of a local politician named Walter Lübcke went viral after he defended then-Chancellor Angela Merkel's progressive immigration policy.

Svenja Meininghaus: People with a very right political world view they started-- hating him on the internet. They started insulting him. They started to incite people to--to kill him. And that went on for about four years.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Online.

Svenja Meininghaus: Yes. Until in 2019, so four years after he gave that speech, he was shot in his head and instantly dead. So that was one of the cases where we see that online hate can sometimes find a way into real life and then hurt people.

After a man with links to neo-Nazis was arrested, Germany ramped up the creation of its online hate task forces. There are 16 units across the country, each with a team of investigators. Frank-Michael Laue, a career criminal prosecutor, leads the Lower Saxony unit.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How many cases are you working on at any time?

Frank-Michael Laue: In our unit, we have about 3,500 cases per year.

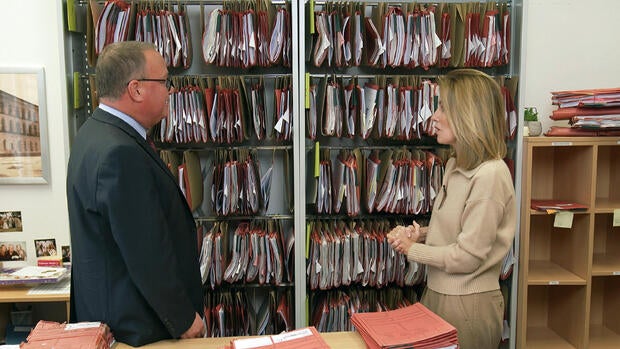

Nine investigators work out of this office in a converted courthouse. Laue says they get hundreds of tips a month from police, watchdog groups and victims. The worst of the internet is wrapped in red case folders, stuffed with printouts of online slurs, threats, and hate.

Frank-Michael Laue: This is a criminal offense, so…

Sharyn Alfonsi: What does that say?

Frank-Michael Laue: (German language - reading the bold text "Kletterpark für Flüchtlinge")

Sharyn Alfonsi: So they're suggesting that the refugee children play in the electrical wires. Okay.

Frank-Michael Laue: This case, the accused had to pay, 3,750 euros…

Sharyn Alfonsi: Wow.

Frank-Michael Laue: It's not a parking ticket.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Not a parking ticket.

To build their cases, investigators scour social media and use public and government data. Laue says sometimes, social media companies will provide information to prosecutors, but not always. So the task force employs special software investigators to help unmask anonymous users.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So this is suggesting you kill people seeking asylum here.

Laue says his unit has successfully prosecuted about 750 hate speech cases over the last four years. But it was a 2021 case involving a local politician named Andy Grote that captured the country's attention. Grote complained about a tweet, that called him a "pimmel," a German word for the male anatomy. That triggered a police raid and accusations of excessive censorship by the government. As prosecutors explained to us, in Germany, it's OK to debate politics online. But it can be a crime to call anyone a "pimmel," even a politician.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So it sounds like you're saying, "It's okay to criticize a politician's policy but not to say 'I think you're a jerk and an idiot.'"

Dr. Matthäus Fink: Exactly. Comments like You're son of a bitch." Excuse me for using, but these words has nothing to do with a political discussions or a contribution to a discussion.

Civility is more than a commandment, for Germans rules are gospel. Even on a quiet street, the crosswalk signal is adhered to with the devotion of a monk. But some here worry by policing the internet, Germany is backsliding.

Sharyn Alfonsi: The criticism is that you know, this feels like the surveillance that Germany conducted 80 years ago. How do you respond to that?

Josephine Ballon: There is no surveillance.

Josephine Ballon is a CEO of HateAid, a Berlin-based human rights organization that supports victims of online violence.

Sharyn Alfonsi: In the United States a lot of people look at this and say, "This is restricting free speech. It's a threat to democracy."

Josephine Ballon: Free speech needs boundaries. And in the case of Germany, these boundaries are part of our constitution. Without boundaries a very small group of people can rely on endless freedom to say anything that they want, while everyone else is scared and intimidated.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And your fear is that if people are freely attacked online that they'll withdraw from the discussion?

Josephine Ballon: This is not only a fear. It's already taking place, already half of the internet users in Germany are afraid to express their political opinion, and they rarely participate in public debates online anymore. Half of the internet users.

Renate Künast is a prominent German politician. In 2015, this meme of the Green Party member appeared on Facebook, falsely implying that she said every German should learn Turkish.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You never said that.

Renate Künast: I never said that. And this harms my reputation. Because people say—I think she's a bit crazy. Gosh, how can she say that?

Künast, a 40-year politician, says she began receiving threats and hate-filled comments from anonymous users online.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You've spent your—a life in politics. What was different about what took place online?

Renate Künast: The first point was it was much more personal, "You're looking so ugly. You are an old woman. You-- we know where you live." Or even-- "You should be raped by a group of men so that you see what all these immigrants are doing."

Sharyn Alfonsi: So this was not elevated conversation. This was very personal and very hateful.

Renate Künast: It was very personal.

Künast asked Meta to delete all the false quotes attributed to her worldwide.

Renate Künast: And they were astonished. "What? We cannot do it," they said. "Just by software, the software is not able to deal with all this." And we have to get a lot of new employees. And the-- I said yes, it's my personal right. It's my reputation.

Künast sued Facebook and won. Last year in a landmark case, a German court ruled Meta had to remove all the fake quotes attributed to her. Meta is appealing.

Renate Künast: This court said, in case of public servants, which have public offices and jobs, it's public interest that their personal rights are protected." Because otherwise no one would go for these jobs, you know? That would harm democracy.

Sharyn Alfonsi: After all this are you seeing less hateful comments now on your social media feeds?

Renate Künast: Yes, there are less hateful comments. And there was one tweet which says, "Don't say that to her, she would take you to court."

Sharyn Alfonsi: You might sue them.

Renate Künast: I might sue them.

Last year, the European Union implemented a new law that requires social media companies to stop the spread of harmful content online in Europe or face millions of dollars in fines. But Josephine Ballon of HateAid says some social media companies are still not complying with the new law.

Josephine Ballon: I would love social media companies to be a safer place than they are right now. But what we see is that their content moderation is not comprehensive. Sometimes it seems to be working well in some areas, but in many areas it's just not.

The European Commission is currently investigating whether Elon Musk's social media company X has breached the EU digital content law. Musk, who has been criticized for using X to promote Germany's far right party ahead of next week's elections, accused the EU of censorship and hating democracy. But in Lower Saxony, prosecutors argue they are protecting democracy and discourse by introducing a touch of German order to the unruly world wide web.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You're doing all this work. You're launching all these investigations. You're fining people, sometimes putting them in jail. Does it make a difference if it's a worldwide web and there's a lotta hate out there?

Dr. Matthäus Fink: I would say yes, because what's the option? The option is to say, "We don't do anything?" No. We are prosecutors. If we see a crime, we want-- to investigate it. It's a lot of work and there are also borders. It's not an area without law.

Produced by Michael Karzis. Associate producer, Katie Kerbstat. Broadcast associate, Erin DuCharme. News associate, Mary Cunningham. Edited by Sean Kelly.