Descendants of key figures in landmark segregation case Plessy v. Ferguson create unlikely friendship

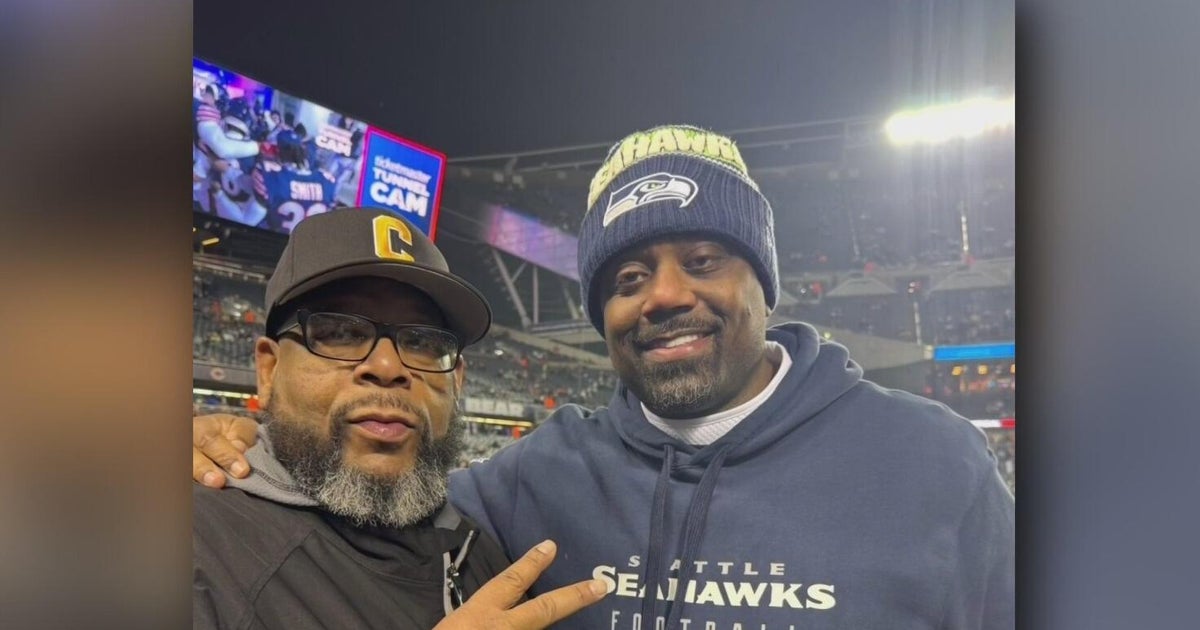

It's a friendship two decades strong between the descendants of two people who turned the course of American history.

Keith Plessy is the distant cousin of an African American shoemaker turned activist. Homer Plessy was tapped to challenge Louisiana's newest segregation law, the Separate Car Act of 1890.

"He looked like a white person, he was one-eighth Black," Plessy told CBS News' Michelle Miller. "He was selected to purchase that ticket. There was a group of people called the Citizens' Committee who organized that."

Eighteen lawyers and prominent citizens came together to defy the law, according to Plessy. The case made its way to the Supreme Court, with Justice John Marshall Harlan as the lone dissenter.

But a Louisiana state judge ruled against Plessy. His name? John Howard Ferguson.

"I remember thinking, 'Well, my name's Ferguson,'" said Phoebe Ferguson, the judge's great-great-granddaughter. "And I think by fourth grade we had learned something about it. I didn't pursue it or ask my parents or anything."

Like Ferguson, Plessy was in the dark about his ancestors for years, with the exception of a paragraph he read about the case in elementary school.

"I never knew that I was related to him," he said.

Ferguson found out about her ancestral connection through a phone call about a property that belonged to her great-great-grandfather.

"I just got a call, and this gentleman had purchased my great-great-grandfather's house on Henry Clay, and he wanted to restore it," she recalled. "He's saying, 'I bought your great, great grandfather's house, the judge in Plessy versus Ferguson. But I didn't know that."

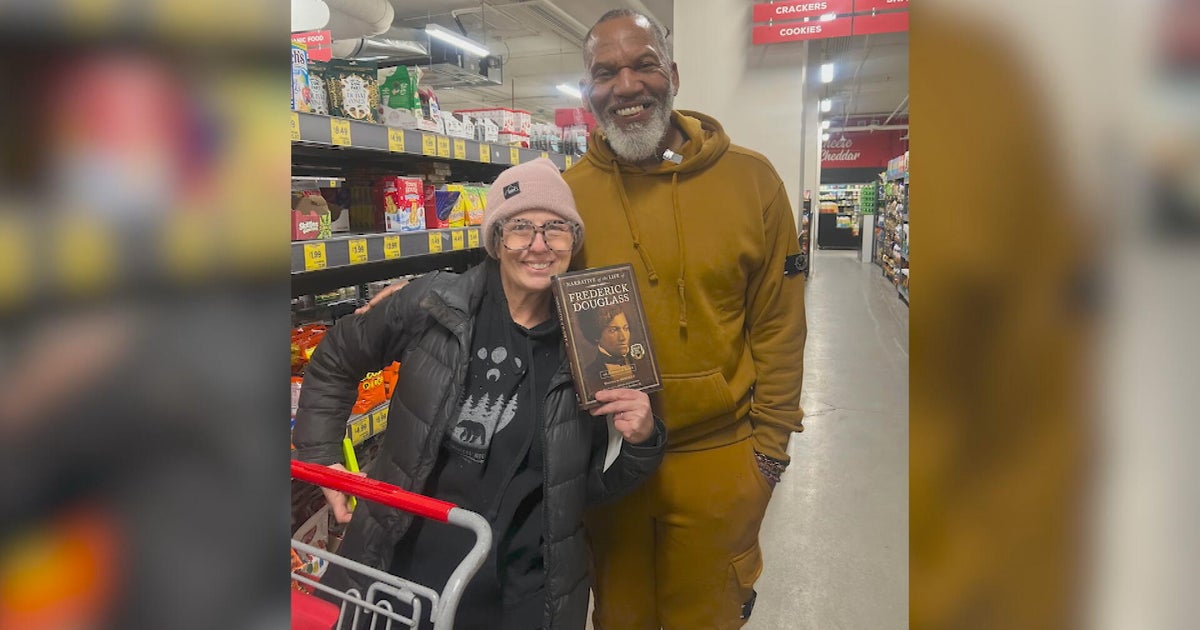

Finding out about her family history got her and Plessy on a mission, she says. After being introduced by author Keith Weldon Medley, the pair launched the Plessy and Ferguson Foundation.

The modern-day Plessy and Ferguson hope to create change by telling the truth about history and helping people understand the meaning of legacy.

"I think it's our responsibility, that's how we look at it," Ferguson said. "We want people to understand what legacy is, and not to wait until the end of your life to understand legacy, but to understand legacy at an early age."

Had the ruling been different, Ferguson said it would have been "the most disastrous decision by the Supreme Court, or one of the most in American legal history."

"America had a chance to mend itself or begin at that time, but instead, after coming through a bloody Civil War and Reconstruction, which really worked, and a person like Homer Plessy had to go and ride a train and break a law in order to get their attention," Plessy said. "Instead, the highest court in the nation sanctions separate but equal."

"At that time, there was enough evidence and enough people who were progressive enough to change this place."

After the death of George Floyd last year and the massive Black Lives Matter protests that followed, both Ferguson and Plessy said they felt sad but hopeful seeing a unified force marching through the streets for justice.

The two think of themselves as "memory preservationists," planting markers around New Orleans to honor Black resistance, like the one that exists near the railroad tracks where Homer Plessy was arrested.

"This gives my life meaning, we really love working together," Ferguson said.

"In my case, I would say it's a calling," said Plessy. "I look at what's happening around us and I try to find solutions rather than to harp on the problem. Working with Phoebe is like therapy."

The duo hopes this therapy can lead to a nation's healing.

"It allows me, and us, to make a difference. Our unity can make a difference, and I am thrilled to be a part of that," Ferguson said.

"As a result of this thing, I'm hoping that we find some common ground," Plessy said. "I think the world is my canvas right now, and the painting I'm going to make is one of peace."