MIT develops plans to deflect "planet-killer" asteroids bound for Earth

It's not often the Earth is at risk of being hit by a giant speeding asteroid from outer space. But on the off chance one is heading our way, MIT scientists want us to be prepared.

A team of researchers there recently developed a system to figure out the best method for avoiding a collision with what they call "planet-killer" asteroids — the largest objects that have the potential to strike Earth. By observing an asteroid's mass and momentum, proximity to a "gravitational keyhole," and the amount of warning time, they believe they can identify the most successful mission to avoid catastrophe.

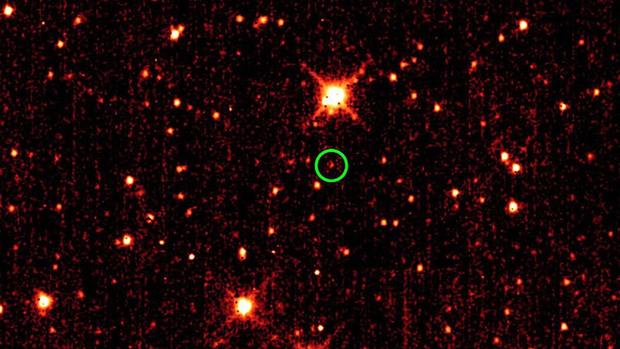

The next planet-killer asteroid to fly through our cosmic neighborhood is expected to pass near Earth on April 13, 2029. The giant icy space rock — known as 99942 Apophis, for the Egyptian God of Chaos — will speed by at over 67,000 miles per hour. Astronomers say it will be one of the largest asteroids to cross that close to Earth's orbit in the next decade.

Early observations suggested Apophis could potentially enter Earth's gravitational keyhole — in other words, come close enough that our planet's gravity would alter its trajectory. That might have put it on track to impact Earth its next time around in 2036. While scientists later determined it should pass by safely both times, they are eager to come up with viable strategies for deflecting any future asteroids that threaten to come too close for comfort.

In a study published this month in the journal Acta Astronautica, researchers at MIT applied their hypothetical deflection methods to the astroids Apophis and Bennu, an asteroid currently being targeted by a NASA mission to return a sample of its surface material to Earth in 2023. They say the method could be applied to deflecting any potentially dangerous near-Earth asteroids.

"People have mostly considered strategies of last-minute deflection, when the asteroid has already passed through a [gravitational] keyhole and is heading toward a collision with Earth," Sung Wook Paek, lead author of the study and a former graduate student in MIT's Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, said in a press release Tuesday. "I'm interested in preventing keyhole passage well before Earth impact. It's like a preemptive strike, with less mess."

In 2007, NASA suggested that launching a nuclear bomb into space would be the most effective method for deflecting an incoming asteroid, but nuclear fallout makes it an options many would rather avoid. Another option would be to send a spacecraft, rocket or another projectile to collide with an asteroid and change its course, requiring a level of precision that may be impossible to achieve.

"Does it matter if the probability of success of a mission is 99.9 percent or only 90 percent? When it comes to deflecting a potential planet-killer, you bet it does," said co-author Olivier de Weck, an MIT professor of aeronautics and astronautics and engineering systems. "Therefore we have to be smarter when we design missions as a function of the level of uncertainty. No one has looked at the problem this way before."

One of the main purposes of the study was to rethink the problem of "planetary defense," researchers said, and create solutions that do not involve nuclear weapons or individual missions, but rather a series of missions to more accurately target such asteroids.

The MIT team simulated 3 different scenarios for dealing with asteroids:

- Using a "kinetic impactor," or a projectile sent into space to attempt to divert the asteroid.

- Sending a "scout" first to gain specific measurements of the asteroid so a more accurate projectile can be used.

- Sending two scouts: one to measure the asteroid and the other to push it slightly off course before a large projectile can be used to ensure it misses Earth, like a game of cosmic billiards.

They say time is the most important factor in determining which method would be best.

If a planet-killer asteroid was more than five years away from entering Earth's gravitational keyhole, sending two scouts and a projectile would be the way to go, the MIT researchers concluded. If we have between two and five years, sending a single scout and a projectile is the safer option. With one year or less, Paek said it may be too late to do anything at all.

"Even a main impactor may not be able to reach the asteroid within this timeframe," he said.

Should an asteroid the size of Bennu or Apophis actually collide with Earth, "the result would be regional devastation the size of a large U.S. state," co-author and MIT professor of planetary science Richard Binzel told CBS News on Thursday. However, neither of those asteroids are currently on track to hit Earth.

If another asteroid did approach, "All we have to do is change its speed a little faster or a little slower so that when it crosses Earth's orbit, it crosses either in front of us or behind us," Dr. Lori Glaze, director of planetary science at NASA, told CBS News last year.

The method developed at MIT could give scientists a handy guide to determine the best course of action before launching a full-scale attack on a potential planet-killer.

But as scary as it sounds, the chances of impact are pretty remote, and experts say everyday citizens shouldn't be too worried.

"It doesn't really keep me up at night," Glaze said.