Pianist Jeremy Denk on how practice makes perfect

"That's a very good cheese, you know?" said Jeremy Denk. "You could have a more French cheese. But then, you know, sometimes you want a good old German cheese, you know?"

Why is this man at the piano talking about cheese? Because the classical pianist is trying to put his finger on classical music, and he knows that means more than putting his fingers on the keys.

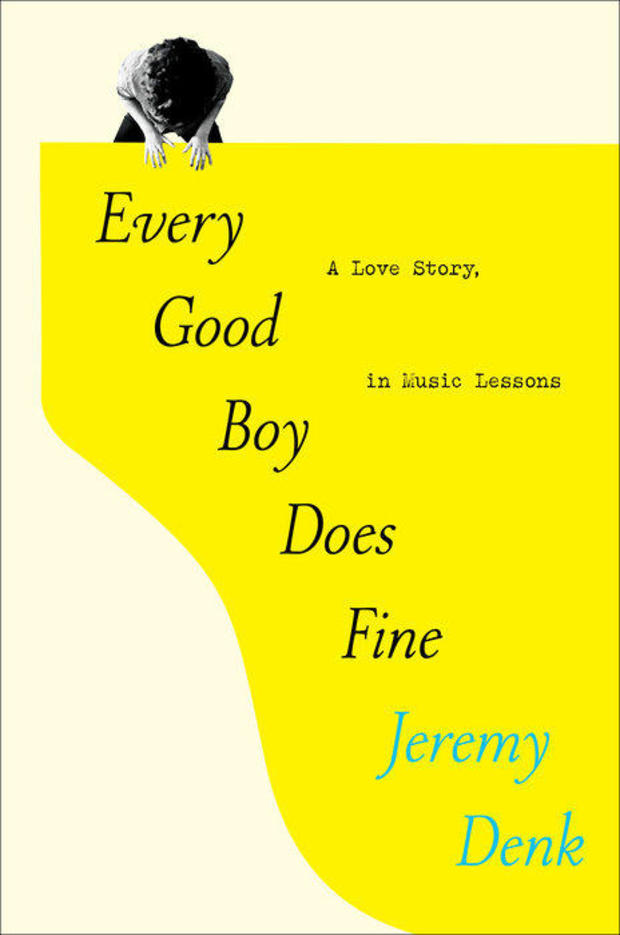

Denk, an award-winning pianist, is the author of "Every Good Boy Does Fine" (Random House), a performer's love song to the craft of the thing piano students usually hate: practice.

Young Denk's first musical lesson took place not at the piano but on the sofa of his boyhood home in New Jersey: "One of my father's favorite pieces was the Saint-Saëns Symphony No. 3, the 'Organ' symphony. About-three quarters of the way through the piece, where the orchestra is diminuendoing, my dad called me up to the couch and he was like, 'Listen.'

"And we're listening, you know? And then suddenly this organ comes up with THE LOUDEST C-MAJOR CHORD EVER. And my dad looked over at me and he said, 'Holy crap!'"

CBS News correspondent john Dickerson asked, "You say it's your first musical lesson; what did you learn?"

"The sheer joy of surprise in music," Denk replied. "I think that was part of what we shared on the couch there."

Having felt the connection between music and emotion, head and heart, Denk, age 10, had to learn to settle his hands. "We moved to New Mexico, and I had a new teacher who at the New Mexico State University, William Leland," he said.

Together, they kept a notebook marking his progress.

Dickerson asked, "Through the drawings in your book, he seemed to have an aptitude for communicating with a ten-year-old."

"But I was a weird ten-year-old also, you know? A little bit, like, you know, partly ten years old and partly 50. And he was very determined to build me a technical foundation so that I could actually realize some of the things that I was trying to do musically.

"He made me play – he thought my thumbs were weak, which they were! So, you had to think about, 'Keep your hand quiet and bring your thumb like a little crab under the hand, right? And then go further. Then go a little, and then go further, right?' He made me do this for, oh God, unbelievable hours, you know? It's even traumatizing me right now to think of it to play it," Denk laughed.

"It seemed like the most miserable possible enterprise, you know? I think the whole point of piano lessons was to drain all the pleasure from music, you know?"

Dickerson asked, "Why didn't it drain all the pleasure out of it for you?"

"It did at moments," said Denk. "But then, I would listen to some piece, and then you know, like, 'Oh yes, this is what music is for.'"

"Do you feel any fellow feeling with Olympic athletes? They've done all the kinds of practice that you write about and that you do, and then the moment comes. Is that similar at all?"

"It's so similar that I can barely watch Olympic competition!" he replied.

WEB EXTRA: Pianist Jeremy Denk on his childhood compositions

Denk's love of the music grew, despite the hours of practice, leading to a bout of evangelical fervor on the bus to school: "I was not a fan of popular music in those days. I was an extremely elitist little brat, you might say! And I thought, you know, 'People need to learn that there's something better out there to listen to.'"

So, he stuffed a cassette player in his backpack, got on the bus, and pushed play. "The conversation, like, slowly comes to a halt, and people are looking around, you know, with this horrible, you know, like, 'What is that terrible smell?'" he laughed.

As skilled in the classroom as at the piano, Denk left for the prestigious Oberlin Conservatory of Music at age 16. There, he found teachers who pushed him almost as much as he pushed himself.

Dickerson asked, "Is there something intrinsic to the teaching of classical piano that requires hard teaching?"

"There is a long tradition of mean, you know, abusive teaching," said Denk. "You know, even the teachers that were meanest to me, I'm still assuming they did it, you know, because I needed it, yeah, in a way. But sometimes they didn't realize what a sea of anxiety and insecurity I was, you know, underneath."

Denk won the highly-competitive senior concerto competition at Oberlin, and was set to move to his next teacher in California. But after hearing György Sebők, he moved to Indiana instead to study under him.

"I had never really loved Bach until that moment, in a way," said Denk. "The way he played that, moving his hands so smoothly and beautifully, but also with this little smile, you felt that his smile, physical smile, was also present in the notes, too, that the music had this beatific quality, but also this sense of play. And I don't think many of my teachers had told me to play with play yet.

"I think I so desperately needed what Sebők was offering at that moment, that I needed a sense of the wider purpose of piano playing, and also this European perspective. What is the emotional meaning? Like, the musical score is like a treasure map, you know, telling you, you know, 'Here's how you create this piece, you know? Here's how you bring it alive. Here's how you do it.' And it's not a misery, it's a beautiful guide."

The mixture of technique and play has won Denk critical acclaim, including a MacArthur "genius" grant. He now tours the world, playing with great orchestras and sometimes classical music superstars like Joshua Bell.

Practicing, now, is a joy in itself.

Dickerson asked, "How long can you go without practice? What happens if it gets into, about, the middle of the second day?"

"It's like an itch," said Denk. "Maybe it's an addiction in a certain way, you know? Like, I feel my fingers start to do things, you know, and I can't sit still. It's that act of translating through the body that I somehow need, you know, to feel complete.

"I'm happy to play excellently. I'm very, you know, soothed when I feel I've played well as a pianist. But I'm much happier if I feel that something of that quality when I'm practicing gets transferred to everyone in the room."

"You've given them something?"

"Yes, which is, allowing the audience in, but also allowing the music to speak and allowing the time to feel generous."

It is the kind of generosity that Denk felt 46 years ago on that couch in New Jersey, and after countless lessons and hours of practice, he can now give a similar lesson just by sitting down to play.

READ A BOOK EXCERPT: "Every Good Boy Does Fine" by Jeremy Denk

For more info:

- "Every Good Boy Does Fine: A Love Story, in Music Lessons" by Jeremy Denk (Random House), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon and Indiebound

- jeremydenk.com

- Bing Concert Hall, Stamford, Calif.

- Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University Bloomington

- Indiana University Archives

- Oberlin Conservatory of Music, Oberlin, Ohio

- Thanks to the family of photographer Louis Ouzer, and the Sibley Music Collection, Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester

- New Mexico State University Library Archives & Special Collections

- "At Home with Music" video footage courtesy of Joshua Bell, Inc., Park Avenue Artists, and Dramatic Forces

Story produced by Mary Lou Teel. Editor: Emanuele Secci.