Pay Attention: How sensory deprivation and floating impact the mind

Our series Pay Attention looks at how to retrain our focus and recapture our attention under the bombardment of technology and information that distracts us. The average person scrolls through 300 feet of mobile content a day, according to Facebook's global creative director, Andrew Keller. That's almost the length of a football field. We wanted to explore some of the ways people are trying to short-circuit the noise, from the mundane to the extreme – and that's how "CBS This Morning" co-host John Dickerson ended up floating in a sensory deprivation tank in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Floating in less than a foot water, buoyed by 2,000 pounds of salt, Dickerson felt weightless, unsure where his limbs end and the water starts. And at some point, the sensation is one of losing himself, never falling asleep but moving into a state of a clear but empty mind.

Sensory deprivation is about as far as a person can get from the chirpy world of breaking news, social media, email and the rest of what pinballs through our heads these days.

For the past six months, entrepreneur Scott McKenzie has floated three to six times a week in Southern California. "To have that nothingness and be forced to just decompress... there's something revitalizing about it," the Golden Age Companions CEO and owner said.

McKenzie said that "nothingness" has opened up his mind to new business ideas.

"What it does is it keeps me more focused," he said. "You realize, 'Wow, like my mind had a whole reboot.'"

Around since the 1950s, floating is now resurfacing as an alternative therapy for physical and mental health. Elite athletes like Golden State Warriors star Stephen Curry claim it helps with mental focus.

"It's the only place that I've found in this world that you can eliminate all the senses basically. To be able to try to master your thoughts," Curry says in a Kaiser Permanente video. "You rarely find the opportunity to do that."

We met neuropsychologist Justin Feinstein at the Laureate Institute for Brain Research. He studies the impact of floatation therapy on patients with anxiety disorders and PTSD.

"We created a room around the pool that was built to be soundproof, lightproof, temperature controlled," Feinstein said. "In fact, we're trying to match the temperature of the water to the temperature of your skin, which is a few degrees cooler than core, so about 95 degrees."

He is one of the few scientists researching floating, which is how Dickerson ended up in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

"We're going to turn you into a bionic man," Feinstein said, as a wireless, waterproof EEG was strapped onto Dickerson's forehead and he was fitted with a heart-rate monitor and a blood pressure cuff.

"If I am in the busy world of constant interruptions, shredded attention, how can a good float help me with that?" Dickerson asked.

"Think about what a strange world our brains find themselves in, suddenly inundated with 24/7 connectivity. … So here in many ways you have the ultimate form of disconnection," Feinstein said.

Feinstein monitored Dickerson's vitals next door. His heart rate dropped by 20 beats per minute and his blood pressure dropped more than 20 points. Dickerson was not asleep but powered down to just a flicker.

"By the end of the float you were getting to about two to three breaths a minute, which was incredibly low," Feinstein noted.

So low that there is a biological effect on the brain – essentially telling it to "quiet down."

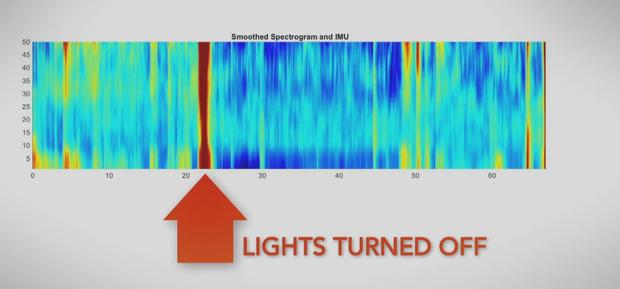

Neurophysiologist and Neuroverse co-founder Ricardo Gil-da-Costa developed the technology that measured Dickeron's brain activity.

"If you look at the first 21, 23 minutes on the float, we see more activity, which is not uncommon. You are trying to relax," Gil-da-Costa said.

After 65 minutes of floating in silent darkness, Dickerson noted he was relaxed but also energized. He had totally lost track of time.

"I could go for that every day. I don't think my office can fit that, but that would be great," Dickerson said.

An hour in the tank, however, is not for everyone.

"Some people might find that very restful. Some people might find that it freaks them out," said Dr. Philip Muskin, a psychiatrist at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University.

"The problem in a busy day, you're taking an hour off to go to a flotation tank where there are other things you could do that might really benefit you," Muskin said.

But Muskin said taking these breaks and "emptying your mind," as Dickerson called it, can help control people's attentions.

"Attention is a biological phenomenon," Muskin said. "When you empty your mind, be that by breath, floatation, meditation, exercise… it works by allowing our brains to do some discharge of the junk and let us go back to work."

"I don't know if this is going to be the solution, ultimately, to all of the problems that technology may end up causing our nervous system, but it seems like a very simple way to at least give a respite," Feinstein said.

Feinstein is in the middle of his research. It's still experimental. The big discovery would be if those who use a float tank become so familiar with its quietude that they can access it even when not in the tank.