What the U.S. is committing to as it rejoins the Paris climate accords — and why it matters

On Friday, the United States will reenter the Paris Agreement, a climate treaty dedicated to lowering greenhouse gas emissions in more than 180 countries around the world. It was originally signed and negotiated during the final years of the Obama administration, withdrawn from by President Trump in 2020, and reentered by President Biden on his first day in office.

The drafting of the agreement took place at the 21st Conference of the Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, also known as COP21. The treaty was originally signed by 175 countries, and included commitments from the world's leading CO2 emitters: China, the United States and the European Union. Today, 189 parties representing 97% of global emissions have joined, according to the World Resources Institute.

The agreement's objective is to prevent the global average temperature from warming beyond a point of catastrophe, defined as "well below" a 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) increase compared to pre-industrial levels. To slow the warming, countries agreed to finance programs and share resources with the goal of becoming carbon neutral by 2050.

The agreement mandates that the parties "aim to reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible." Then, by lowering emissions goals every five years, each nation is meant to decarbonize over time.

Each nation is responsible for setting their own emissions goals. The agreement also incorporates smaller nations, which are not responsible for large emissions but often feel the greatest effects of climate change, such as sea level rise.

The lack of mandated standards make the Paris Agreement unique. It was specifically designed in light of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which only included 36 countries, dictated goals, and ultimately failed to significantly reduce global greenhouse gas emissions.

The Paris Agreement's metric for tracking emissions targets is "nationally determined contributions," or NDCs. Each party to the treaty is asked to prepare successive NDCs that it plans to achieve.

The agreement mandates NDC targets change every five years and reflect each country's "highest possible ambition." NDCs are reported to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Secretariat and filed into an official public registry.

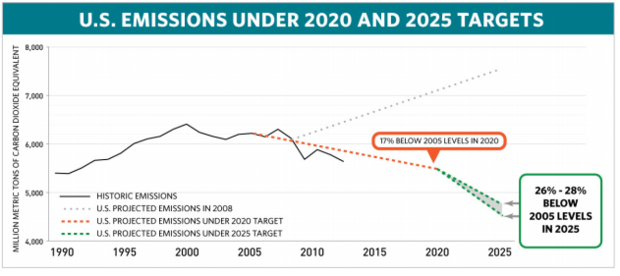

When the U.S. signed the agreement in 2016, its first NDC target was to get "in the range" of an economy-wide 17% drop below 2005 greenhouse gas levels by 2020. It also aimed to achieve a subsequent decrease of 9-11% of 2005 levels by 2025, meaning the U.S. would reduce greenhouse emissions by 26%-28% in the first ten years of the Paris Agreement.

Former US Special Envoy on Climate Change and President Obama's chief climate negotiator on the Paris Agreement, Todd Stern, told CBS News that it was important at the time for the U.S. to declare an ambitious goal, setting a good example for other nations.

"Some countries pick a target that's really easy and then they pat themselves on the back when they meet it," said Stern. "We took the opposite approach."

Stern said the U.S. would be "well on its way" to reaching the 2025 goal had a Democrat succeeded President Obama.

While President Trump's exit from the Paris Agreement sent a negative and confusing message to the international community, Stern said, it was Mr. Trump's climate policies and regulation rollbacks that ultimately had an effect on the trajectory of U.S. emissions.

Nevertheless, the U.S. is still on track to meet its NDC goal, due in large part to COVID-19. The U.S. saw a 9% drop in greenhouse gas emissions over the past year, the most significant fall on record, according to a joint report from The Business Council for Sustainable Energy and the Bloomberg New Economy Forum. That shift won't be permanent, however, as the country will eventually recover from the pandemic.

COVID-19 also caused a delay in the five-year update schedule. COP26, originally planned for November 2020, will now be held this November in Glasgow, Scotland. Stern said the meeting is crucial for the U.S. for two reasons: It will require the country to present new NDC targets and it will reestablish America as a leader in fighting the climate crisis.

Just in the five years since Paris was adopted, Stern said, there's been a consensus among experts to keep global warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius, not 2 degrees.

"The goalposts have significantly moved," he said, citing new research and an uptick in severe weather as the reason for the shift. "Two was already super difficult. 1.5 is exceedingly difficult."

For that reason, Stern said the U.S. needs to present a big target in order to convince other countries — particularly China, the world's leader in greenhouse gas emissions — to do the same.

"You never have impact unless you're walking the walk, not just talking the talk. The U.S. is going to have to produce a really ramped up NDC target for 2030," Stern said.